Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko

Содержание

- 1. Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko

- 2. Taras Shevchenko (1814-61) was a Ukrainian author

- 3. Born into serfdom, Shevchenko experienced poverty from

- 4. The first half of the 1840s is

- 5. He was then exiled with a military

- 6. Literary OeuvreShevchenko's literary oeuvre consists of one

- 7. Early Works (1837–1843)Shevchenko’s early works include the

- 8. The Period of Three Years (Try

- 9. Cycle ‘V kazemati’ (In the Casemate,

- 10. The Exile PeriodIn his ‘bootleg booklets’ he

- 11. The Last Period of Shevchenko's CreativityThe last

- 12. "Testament" (Zapovit) Shevchenko's "Testament" (Zapovit, 1845) has

- 13. Shevchenko’s ArtThe great poet, ardent patriot, thinker

- 14. The themes of Shevchenko’s works, depicting life

- 15. PortraitsShevchenko’s portraits have a broad social range

- 16. Picturesque UkraineIn the spring of 1843, after

- 17. Exile PaintingsThe genre themes in the creative

- 18. Shevchenko has had a unique place in

- 19. Скачать презентанцию

Слайды и текст этой презентации

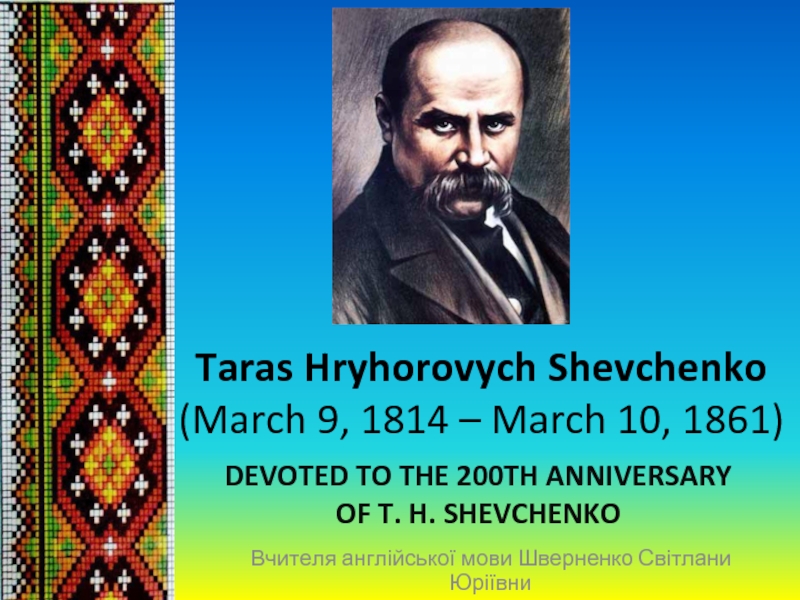

Слайд 1Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko

(March 9, 1814 – March 10, 1861)

DEVOTED TO THE

200TH ANNIVERSARY OF T. H. SHEVCHENKO

ЮріївниСлайд 2Taras Shevchenko (1814-61) was a Ukrainian author and artist. The

Kobzar, which he worked on for nearly 25 years, is

considered his masterpiece. His works are celebrated worldwide in museums and cultural centres named after him. There are about 1250 monuments to him in Ukraine and another 125 overseas. Shevchenko has a special place in Ukrainian history: his poetry is considered to be a foundation for modern written Ukrainian and for Ukrainian literature. Aside from his literary work, his paintings earned him many awards and a professional title from the Imperial Academy of Arts.Слайд 3 Born into serfdom, Shevchenko experienced poverty from an early age.

By the age of 11, he had lost both his

parents, but before passing away, his father managed to get him an apprenticeship with a deacon, who taught the young boy to read and write. After the death of his parents, Shevchenko was an itinerant worker until the age of fourteen, when he became a house servant with his overlord, Pavel Engelhardt. The boy showed early talent for art. At 15, he travelled with Engelhardt to St. Petersburg and was given a series of apprenticeships. Eventually, he came to the attention of several prominent intellectuals, including Russia’s finest living painter, Karl Briullov, and poet Vasilii Zhukovsky, who was the tutor of future Czar Alexander II. They bought Shevchenko’s freedom for 2,500 rubles by auctioning off one of Bruillov’s portraits of Zhukovsky. In 1838, Shevchenko was accepted into the Imperial Academy of Arts as Briullov’s student.Слайд 4The first half of the 1840s is considered propitious for

the artist. Having written poetry since 1837, Shevchenko published his

first Kobzar in 1840. The collection earned him critical and popular acclaim, and his status as a cultural figure was on the rise. He returned to Ukraine for the first time at the age of 29, travelling extensively for a critical three year period from 1843-45 that resulted in a series of paintings and some of his most penetrating and patriotic verse. In Kyiv, he joined the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, a secret organization that advocated the abolition of serfdom and also the right of every Slavic nation to develop its own culture and language.Слайд 5 He was then exiled with a military detachment to Orenburg

on the edge of the Ural Mountains. Czar Nicholas I

personally prohibited Shevchenko from writing or painting. Shevchenko, however, violated the Czar’s orders. Such insubordination led to even deeper banishment to the town of Novopetrovsk on the desolate eastern shore of the Caspian Sea. (In honour of the poet, the city was renamed Shevchenko in 1963). His friends, including members of the prominent Tolstoy family, appealed for his release, which finally came in 1857. Shevchenko’s health was permanently affected by the ordeal, but his creative output remained strong. In 1860, the Imperial Academy of Arts honoured the artist with a professional academic title. Soon after, his health deteriorated and he died of heart failure on March 10, 1861— seven days before the abolition of serfdom was formally announced.Слайд 6Literary Oeuvre

Shevchenko's literary oeuvre consists of one mid-sized collection of

poetry (Kobzar); the drama Nazar Stodolia and two play fragments;

nine novellas, a diary, and an autobiography written in Russian; four articles; and over 250 letters.Слайд 7Early Works (1837–1843)

Shevchenko’s early works include the ballads ‘Prychynna’ (The

Bewitched Woman, 1837), ‘Topolia’ (The Poplar, 1839), and ‘Utoplena’ (The

Drowned Maiden, 1841) poems ‘Tarasova nich’ (Taras's Night, 1838), ‘Ivan Pidkova’ (1839), Haidamaky (1841), Romantic drama Nazar Stodolia (1843–44) . Of special note is Shevchenko’s early ballad ‘Kateryna’ (1838), dedicated to Vasilii Zhukovsky in memory of the purchase of Shevchenko's. In it he tells the tale of a Ukrainian girl seduced by a Russian soldier and abandoned with child—a symbol of the tsarist imposition of serfdom in Ukraine.Kateryna (1842)

Слайд 8 The Period of Three Years (Try Lita) (1843–1845)

Through

the poetry of the second period of literature activity Shevchenko

gained the stature of a national bard. Having spent eight months in Ukraine at that time, Shevchenko realized the full extent of his country's misfortune under tsarist rule and his own role as that of a spokesperson for his nation's aspirations through his poetry. He wrote the poems ‘Rozryta mohyla’ (The Ransacked Grave, 1843), ‘Chyhyryne, Chyhyryne’ (O Chyhyryn, Chyhyryn, 1844), ‘Try lita’ (1845), ‘Mynaiut' dni, mynaiut' nochi’ (Days Pass, Nights Pass, 1845), and satire poems ‘Son’ (A Dream, 1844), ‘Velykyi l'okh,’ ‘Kavkaz’ (‘Caucasus’), ‘Kholodnyi Iar,’ and ‘I mertvym, i zhyvym …’ (To the Dead and the Living, 1845.), a cycle of poems titled ‘Davydovi psalmy’ (David’s Psalms), historical poem ‘Ivan Hus,’ ‘Ieretyk’ (‘Heretic‘, 1845).Слайд 9 Cycle ‘V kazemati’

(In the Casemate, 1847)

Shevchenko wrote his poetic

cycle ‘V kazemati’ (In the Casemate) in the spring of

1847 during his arrest and interrogation in Saint Petersburg. It marks the beginning of the most difficult, late period of his life (1847–57). The 13 poems of the cycle contain reminiscences (the famous lyrical poem ‘Sadok vyshnevyi kolo khaty’ (‘The Cherry Orchard by the House’); reflections on the fate of the poet and his fellow members of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood; and poignant reassertions of his beliefs and his commitment to Ukraine.Слайд 10The Exile Period

In his ‘bootleg booklets’ he continued writing autobiographical,

lyrical, narrative, historical, political, religious, and philosophical poems. Of special interest is

his long poem ‘Moskaleva krynytsia’ (The Soldier's Well, 1847, 2d variant 1857), autobiographical poems ‘Meni trynadtsiatyi mynalo’ (I Was Turning Thirteen, 1847), ‘A. O. Kozachkovs'komu’ (For A. O. Kozachkovsky, 1847), ‘I vyris ia na chuzhyni’ (And I Grew Up in Foreign Parts, 1848), ‘Khiba samomu napysat'’ (Unless I Write Myself, 1849), ‘I zolotoyi i dorohoyi’ (Both Golden and Dear, 1849), and ‘Lichu v nevoli dni i nochi’ (I Count Both Days and Nights in Captivity, 1850, 2d variant 1858), ‘landscape’ poems ‘Sontse zakhodyt', hory chorniiut'’ (The Sun Is Setting, the Hills Turn Dark, 1847) and ‘I nebo nevmyte, i zaspani khvyli’(The Sky Is Unwashed, and the Waves Are Drowsy, 1848), poems ‘Tsari’ (Tsars, 1848, revised 1858) , ‘Irzhavets'’ (1847, revised 1858). Many of his poems became folk songs (such as Reve ta stohne Dnipr shyrokyi (‘The Mighty Dnieper Roars and Bellows’) in their own right.The novellas Shevchenko wrote while in exile were not published during his lifetime. Although written in Russian, they contain many Ukrainianisms. The first two of them—‘Naimychka’ (The Servant Girl, 1852–3) and ‘Varnak’ (The Convict, 1853–4)— share the anti-serfdom themes of Shevchenko's Ukrainian poems with the same titles. Other novellas—‘Kniaginia’ (The Princess, 1853), ‘Muzykant’ (The Musician, 1854–5), ‘Neschastnyi’ (The Unfortunate Man, 1855), ‘Kapitansha’ (The Captain’s Woman, 1855), ‘Bliznetsy’ (The Twins, 1855), ‘Khudozhnik’ (The Artist, 1856), and ‘Progulka s udovol’stviiem i ne bez morali’ (A Stroll with Pleasure and Not without a Moral, 1856–8).

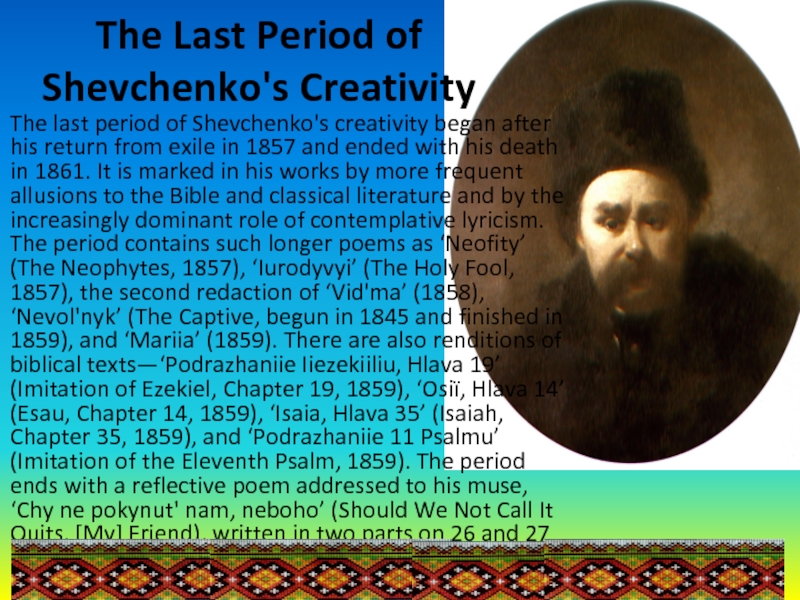

Слайд 11The Last Period of Shevchenko's Creativity

The last period of Shevchenko's

creativity began after his return from exile in 1857 and

ended with his death in 1861. It is marked in his works by more frequent allusions to the Bible and classical literature and by the increasingly dominant role of contemplative lyricism. The period contains such longer poems as ‘Neofity’ (The Neophytes, 1857), ‘Iurodyvyi’ (The Holy Fool, 1857), the second redaction of ‘Vid'ma’ (1858), ‘Nevol'nyk’ (The Captive, begun in 1845 and finished in 1859), and ‘Mariia’ (1859). There are also renditions of biblical texts—‘Podrazhaniie Iiezekiiliu, Hlava 19’ (Imitation of Ezekiel, Chapter 19, 1859), ‘Osiï, Hlava 14’ (Esau, Chapter 14, 1859), ‘Isaia, Hlava 35’ (Isaiah, Chapter 35, 1859), and ‘Podrazhaniie 11 Psalmu’ (Imitation of the Eleventh Psalm, 1859). The period ends with a reflective poem addressed to his muse, ‘Chy ne pokynut' nam, neboho’ (Should We Not Call It Quits, [My] Friend), written in two parts on 26 and 27 February 1861, eleven days before his death.Слайд 12"Testament" (Zapovit) Shevchenko's "Testament" (Zapovit, 1845) has been translated into more

than 60 languages. After being set to music by H. Hladky in

the 1870s, the poem achieved a status second only to Ukraine’s national anthem and firmly established Shevchenko as Ukraine’s national bard.When I am dead, bury me

In my beloved Ukraine,

My tomb upon a grave mound high

Amid the spreading plain,

So that the fields, the boundless steppes,

The Dnieper's plunging shore

My eyes could see, my ears could hear

The mighty river roar.

When from Ukraine the Dnieper bears

Into the deep blue sea

The blood of foes ... then will I leave

These hills and fertile fields –

I'll leave them all and fly away

To the abode of God,

And then I'll pray .... But until that day

I nothing know of God.

Oh bury me, then rise ye up

And break your heavy chains

And water with the tyrants' blood

The freedom you have gained.

And in the great new family,

The family of the free,

With softly spoken, kindly word

Remember also me.

— Taras Shevchenko,

25 December 1845, Pereiaslav

Translated by John Weir, Toronto, 1961

Слайд 13Shevchenko’s Art

The great poet, ardent patriot, thinker and humanist, Shevchenko,

is at one and the same time an outstanding master

of Ukrainian painting and graphic art, the founder of critical realism and the folk element in Ukrainian fine arts; 835 of his art works are extant, and another 270 of his known works have been lost. The creative work of Shevchenko, which was closely tied with the reality of that period and was based on the national-liberation movement, was basically connected with and directed into the future. It is an important stage in the development of realism and the folk element in art. Ukrainian artists refer to the artistic heritage of Shevchenko as one of the greatest and most valuable national traditions.Слайд 14The themes of Shevchenko’s works, depicting life in Ukraine at

that time, are very diverse.

Gipsy Fortune-Teller (1841)

A peasant family

(1843)At the apiary (1843)

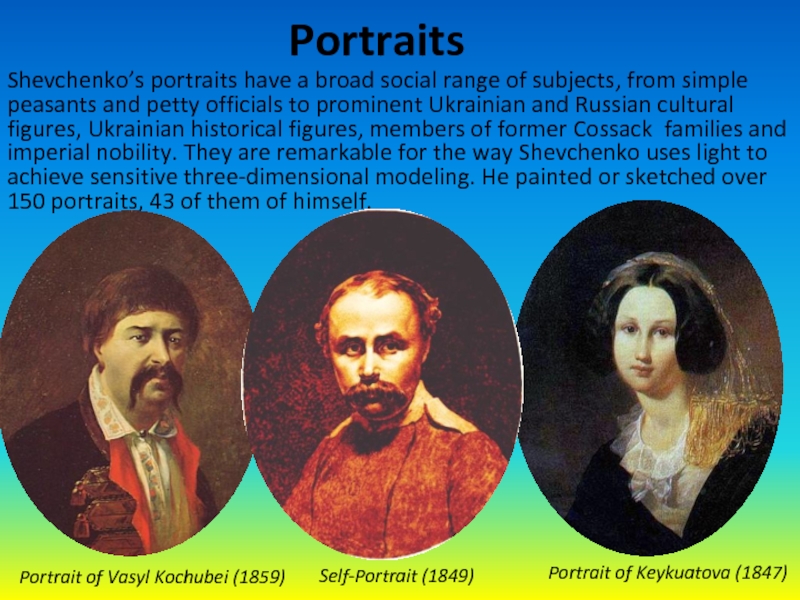

Слайд 15Portraits

Shevchenko’s portraits have a broad social range of subjects, from

simple peasants and petty officials to prominent Ukrainian and Russian

cultural figures, Ukrainian historical figures, members of former Cossack families and imperial nobility. They are remarkable for the way Shevchenko uses light to achieve sensitive three-dimensional modeling. He painted or sketched over 150 portraits, 43 of them of himself.Portrait of Keykuatova (1847)

Self-Portrait (1849)

Portrait of Vasyl Kochubei (1859)

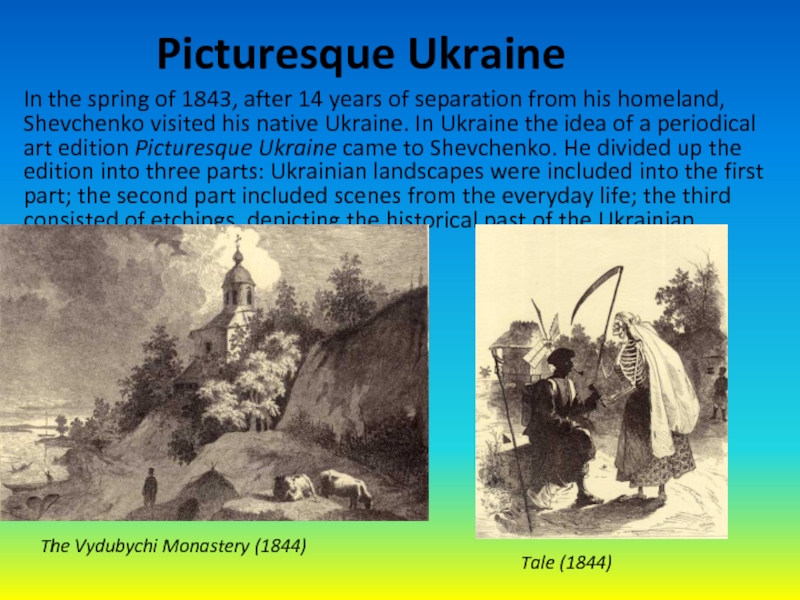

Слайд 16Picturesque Ukraine

In the spring of 1843, after 14 years of

separation from his homeland, Shevchenko visited his native Ukraine. In

Ukraine the idea of a periodical art edition Picturesque Ukraine came to Shevchenko. He divided up the edition into three parts: Ukrainian landscapes were included into the first part; the second part included scenes from the everyday life; the third consisted of etchings, depicting the historical past of the Ukrainian people. The Vydubychi Monastery (1844)

Tale (1844)

Слайд 17Exile Paintings

The genre themes in the creative work of Shevchenko,

during the exile period are also of great importance. Shevchenko

viewed the everyday life of the people, whom Tsarist autocracy called foreigners, with the eyes of a friend. While in exile he depicted the folkways of the Kirghiz and Kazak people, the landscapes of Central Asia and the misery of life in exile and in the imperial army.Kazakh Beggar Children (1853)

Fire in the Steppe (1848)

In the stocks (1856-57)