Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE) — Greek father of medicine Student : Awed ziad

Содержание

- 1. Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE) — Greek father of medicine Student : Awed ziad

- 2. Hippocrates, (born c. 460 BCE, island of

- 3. Слайд 3

- 4. Слайд 4

- 5. It is known that while Hippocrates was

- 6. Hippocrates is credited with being the first

- 7. Слайд 7

- 8. Hippocratic medicine and its philosophy are far

- 9. Hippocrates and his followers were first to

- 10. Слайд 10

- 11. Hippocrates began to categorize illnesses as acute,

- 12. Hippocrates is widely considered to be the

- 13. After Hippocrates, the next significant physician was

- 14. Слайд 14

- 15. Слайд 15

- 16. Скачать презентанцию

Hippocrates, (born c. 460 BCE, island of Cos, Greece—died c. 375 BCE, Larissa, Thessaly), ancient Greek physician who lived during Greece’s Classical period and is traditionally regarded as the father of

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 2Hippocrates, (born c. 460 BCE, island of Cos, Greece—died c.

375 BCE, Larissa, Thessaly), ancient Greek physician who lived during

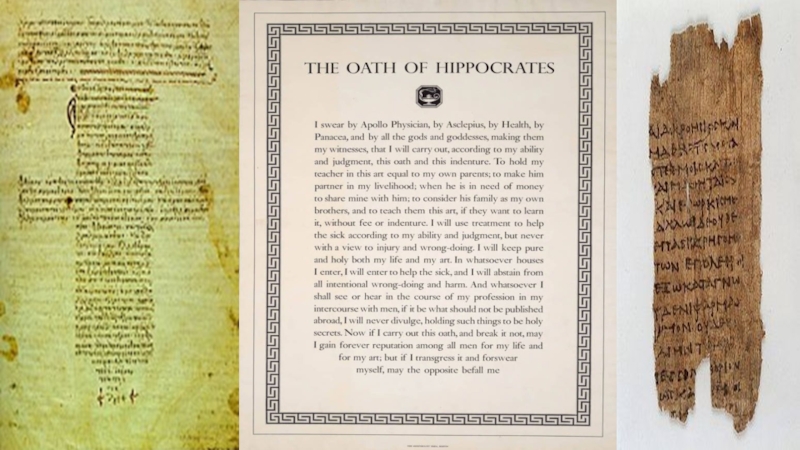

Greece’s Classical period and is traditionally regarded as the father of medicine. It is difficult to isolate the facts of Hippocrates’ life from the later tales told about him or to assess his medicine accurately in the face of centuries of reverence for him as the ideal physician. About 60 medical writings have survived that bear his name, most of which were not written by him. He has been revered for his ethical standards in medical practice, mainly for the Hippocratic Oath.Слайд 5It is known that while Hippocrates was alive, he was

admired as a physician and teacher. His younger contemporary Plato

referred to him twice. In the Protagoras Plato called Hippocrates “the Asclepiad of Cos” who taught students for fees, and he implied that Hippocrates was as well known as a physician as Polyclitus and Phidias were as sculptors. It is now widely accepted that an “Asclepiad” was not a temple priest or a member of a physicians’ guild but instead was a physician belonging to a family that had produced well-known physicians for generations. Plato’s second reference occurs in the Phaedrus, in which Hippocrates is referred to as a famous Asclepiad who had a philosophical approach to medicine.Meno, a pupil of Aristotle, specifically stated in his history of medicine the views of Hippocrates on the causation of diseases, namely, that undigested residues were produced by unsuitable diet and that these residues excreted vapours, which passed into the body generally and produced diseases. Aristotle said that Hippocrates was called “the Great Physician” but that he was small in stature (Politics).

Слайд 6Hippocrates is credited with being the first person to believe

that diseases were caused naturally, not because of superstition and

gods. Hippocrates was credited by the disciples of Pythagoras of allying philosophy and medicine. He separated the discipline of medicine from religion, believing and arguing that disease was not a punishment inflicted by the gods but rather the product of environmental factors, diet, and living habits. Indeed there is not a single mention of a mystical illness in the entirety of the Hippocratic Corpus. However, Hippocrates did work with many convictions that were based on what is now known to be incorrect anatomy and physiology, such as Humorism.Ancient Greek schools of medicine were split (into the Knidian and Koan) on how to deal with disease. The Knidian school of medicine focused on diagnosis. Medicine at the time of Hippocrates knew almost nothing of human anatomy and physiology because of the Greek taboo forbidding the dissection of humans. The Knidian school consequently failed to distinguish when one disease caused many possible series of symptoms.[18] The Hippocratic school or Koan school achieved greater success by applying general diagnoses and passive treatments. Its focus was on patient care and prognosis, not diagnosis. It could effectively treat diseases and allowed for a great development in clinical practice.

Слайд 8Hippocratic medicine and its philosophy are far removed from that

of modern medicine. Now, the physician focuses on specific diagnosis

and specialized treatment, both of which were espoused by the Knidian school. This shift in medical thought since Hippocrates' day has caused serious criticism over their denunciations; for example, the French doctor M. S. Houdart called the Hippocratic treatment a "meditation upon death".Analogies have been drawn between Thucydides' historical method and the Hippocratic method, in particular the notion of "human nature" as a way of explaining foreseeable repetitions for future usefulness, for other times or for other cases