Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

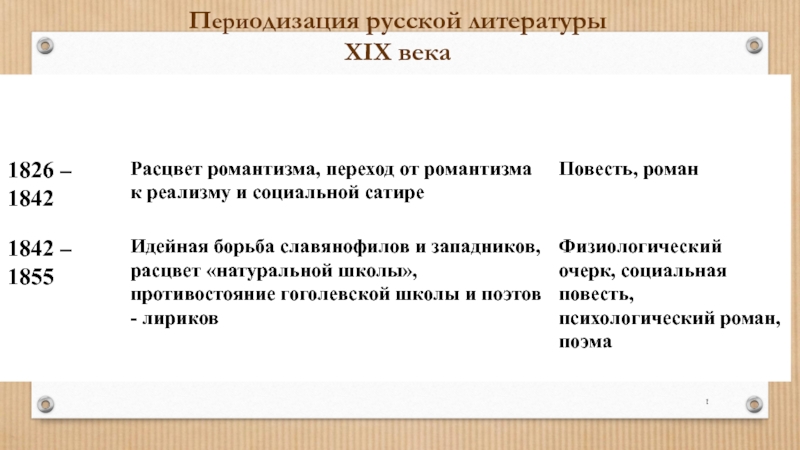

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Bilingualism

Содержание

- 1. Bilingualism

- 2. ContentsWho is a bilingual?Simultaneous bilingual LAOne or two systems?Inhibition theoryBrain benefits of bilingualism

- 3. ”Some people are born bilingual, some aspire

- 4. Who is a bilingual?Being native-like in 2

- 5. A continuumWhile many people might define a

- 6. Bilingual experienceImmigration The family speaks a heritage

- 7. Simultaneous bilingual childrenAre exposed to 2 languages

- 8. Simultaneous bilingual LAPhoneticsInfants can detect the contrasts

- 9. VocabularyThe child’s first word appears at 1

- 10. VocabularyBy 1.5 y.o. the monolinguals’ and bilinguals’

- 11. Слайд 11

- 12. GrammarFirst word combinations – 1.5 y.o. in

- 13. Unitary language system?Language mixing during the early

- 14. A unitary language system would predict:Lack of

- 15. Counter-evidence (vocab)Nicoladis & Secco (2000), Nicoladis &

- 16. Counter-evidence (syntax)Paradis, Nicoladis & Genesee (2000)French/English bilinguals(N=15;

- 17. ‘In order to uphold the unitary-system hypothesis

- 18. Differentiated language systems?Mixing can occur because: the

- 19. We need evidence that the children use

- 20. Genesee et al. 1995 Language differentiation in

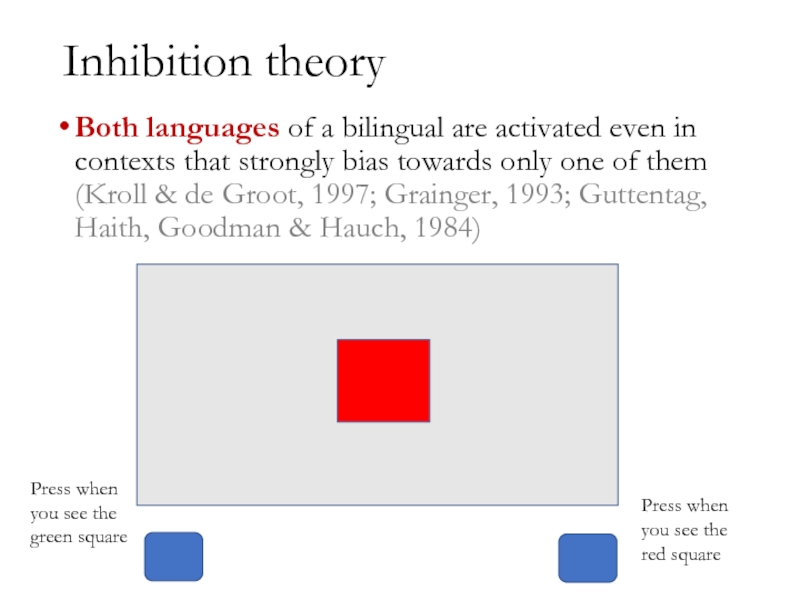

- 21. Inhibition theoryBoth languages of a bilingual are

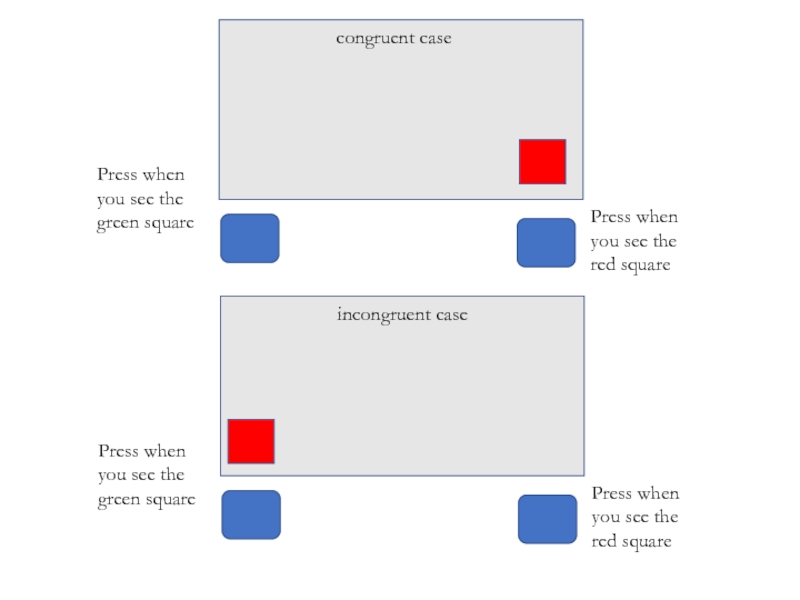

- 22. Press when you see the green squarePress

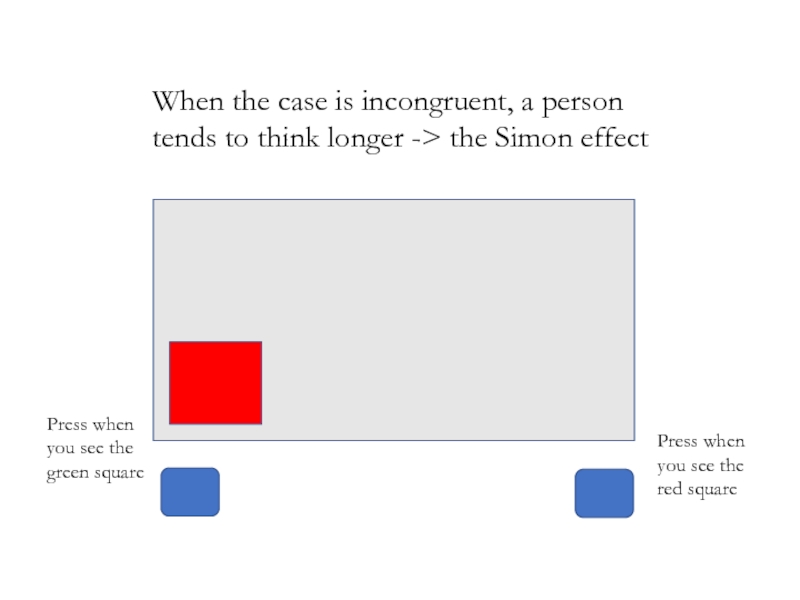

- 23. Press when you see the green squarePress

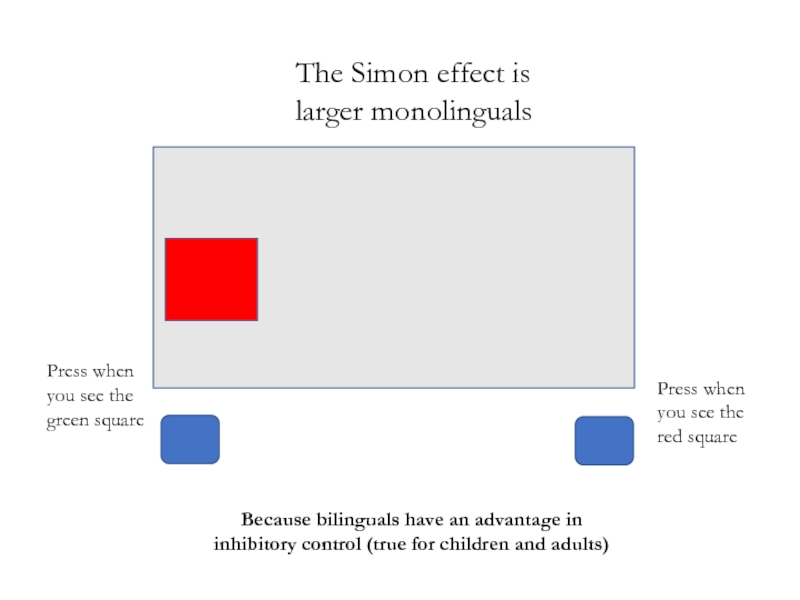

- 24. Press when you see the green squarePress

- 25. Слайд 25

- 26. Слайд 26

- 27. Code-switchingTo compensate for the lack of language

- 28. SummaryNo evidence to suggest that infants can/should

- 29. Have you learned anything new?

- 30. ReferencesBialystok E, Craik FIM, Green DW, Gollan

- 31. Скачать презентанцию

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 2Contents

Who is a bilingual?

Simultaneous bilingual LA

One or two systems?

Inhibition theory

Brain

benefits of bilingualism

Слайд 3”Some people are born bilingual, some aspire to bilingualism, and

others have bilingualism thrust upon them later in life”

(Bialystok,

Craik, Green & Gollan, 2009).

Слайд 4Who is a bilingual?

Being native-like in 2 languages?

Being fluent in

2 languages?

Can speak and understand 2 languages?

From birth?

Equal mastery?

Слайд 5A continuum

While many people might define a bilingual as a

person who can speak two languages with native-like fluency, this

‘gold standard’ is often unreasonable and unattainable. Bilingualism exists on a continuum, where a speaker has varying levels of linguistic proficiency in a first language and a second language.L2

L1

L1

L2

L1

L2

L2

L1

L2

L1

L2

L1

Слайд 6Bilingual experience

Immigration

The family speaks a heritage language

Parents speak different

languages

Family history

Formal education in L2 (bilingual schools)

L2 as a foreign

language at schoolTemporary residence

Political / historical reasons

Слайд 7Simultaneous bilingual children

Are exposed to 2 languages from birth in

their families

Still have a dominant language

Majority/minority language?

Research is contradictory:

“1 month

old – already sequential”“only at 3 years old does a child become sequential, not simultaneous”

Слайд 8Simultaneous bilingual LA

Phonetics

Infants can detect the contrasts that define the

phonological system for all human languages almost from birth (/pa/

vs. /ba/) (Eimas, Sequeland, Jusczyk & Vigorito, 1971).If the contrast is not heard in the environment (/l/ vs. /r/ in Japanese) the ability begins to decline at about 6 m.o. (Werker & Tees, 1984)

Develop a full phonological system at 14 m.o. (same as monolinguals)

Слайд 9Vocabulary

The child’s first word appears at 1 y.o. regardless of

how many languages are spoken in the environment (Pearson, Fernandez

& Oller, 1993) and whether they are both verbal or one of them is signed (Pettito et al., 2001)The RATE and the STRATEGIES of VA are different

E.g. the mutual exclusivity constraint is weaker in bilinguals and even weaker in multilinguals (Byers- Heinlein & Werker, 2009).

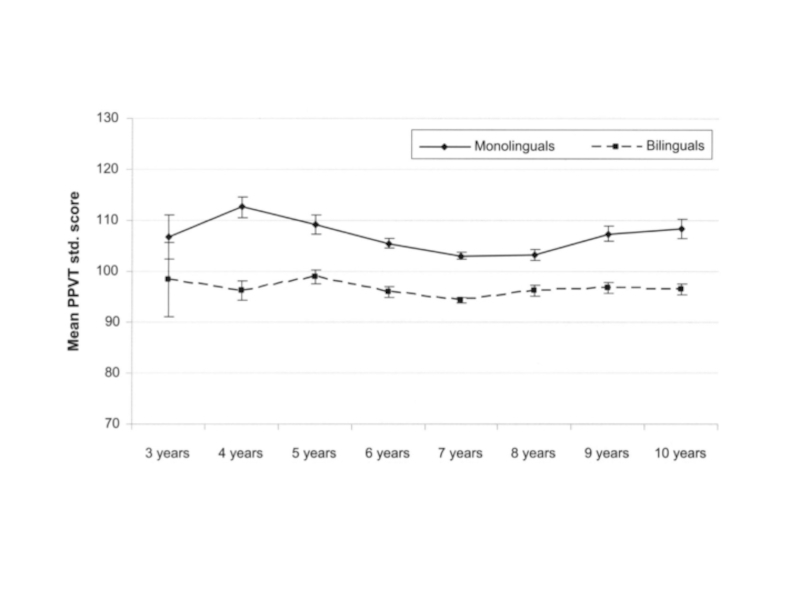

Слайд 10Vocabulary

By 1.5 y.o. the monolinguals’ and bilinguals’ vocab size is

similar (appx. 50 w), but bilinguals know significantly fewer words

in each on the 2 languagesDifficulties?

Do childish sounds count as words if they have consistent meaning? / do we count proper names in both languages? / cognates?

3-10 y.o.: bilinguals have smaller receptive vocab in (L2-Eng) associated with their homes than monolinguals (L1-Eng) (as opposed to “school” vocab) (Bialystok, Luk , Peets & Yang, 2010)

Слайд 12Grammar

First word combinations – 1.5 y.o. in both bilinguals and

monolinguals (Pearson et al., 1993)

Linguistic knowledge for bilingual children is

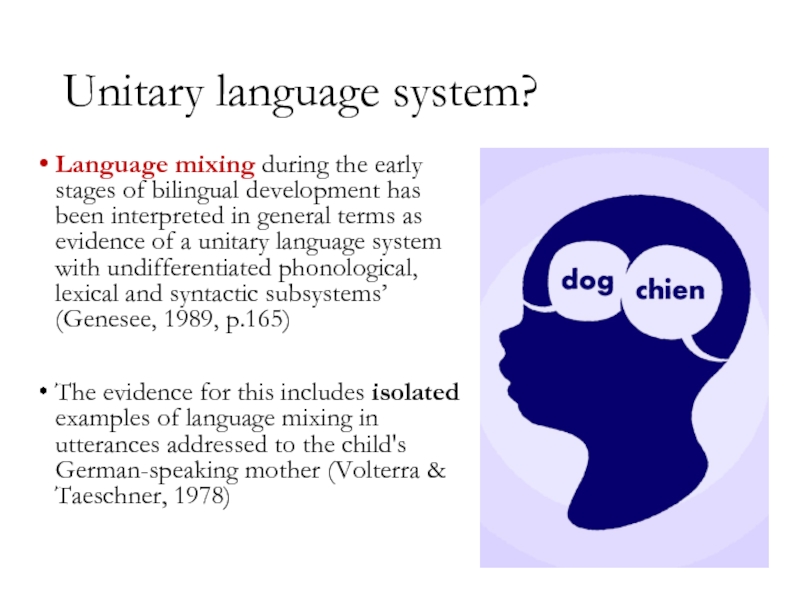

divided between 2 languages, therefore the richness of the representational system is different from that of a monolingual speaker. Similarities in developing cognitive abilities keep the process of language acquisition on a common time courseСлайд 13Unitary language system?

Language mixing during the early stages of bilingual

development has been interpreted in general terms as evidence of

a unitary language system with undifferentiated phonological, lexical and syntactic subsystems’ (Genesee, 1989, p.165)The evidence for this includes isolated examples of language mixing in utterances addressed to the child's German-speaking mother (Volterra & Taeschner, 1978)

Слайд 14A unitary language system would predict:

Lack of equivalents at the

first stages (Volterra & Taeschner, 1978)

Language mixing regardless of the

contextBilingual early language is significantly different from monolingual early language

Slower development as languages are not separate from the beginning

Слайд 15Counter-evidence (vocab)

Nicoladis & Secco (2000), Nicoladis & Genesee (1996) –

show translation equivalents at early stages

Pearson, Fernandez & Oller (1995)

30%

of bilingual toddlers’ vocabularies = language equivalentsWhy only 30%?

Because children do not duplicate every experience in 2 languages at the same time

Слайд 16Counter-evidence (syntax)

Paradis, Nicoladis & Genesee (2000)

French/English bilinguals(N=15; 2.5-3 y.o.)

French: Le

bebe ne boit pas le lait

English: The baby is not

drinking the milkNo stage of mixing the rules

Слайд 17‘In order to uphold the unitary-system hypothesis one would need

to establish that, all things being equal, bilingual children use

items from both languages indiscriminately in all contexts of communication. In other words, there should be no differential distribution of items from the two languages as a function of the predominant language being used in different contexts. (p.165)Слайд 18Differentiated language systems?

Mixing can occur because:

the language system in

use at the moment is incomplete and does not include

the grammatical device needed to express certain meaningsthe grammatical device required to express the intended meaning is available in the language currently in use, but it is more complex than the corresponding device in the other language system and its use strains the child's current ability.

Слайд 19We need evidence that the children use items from their

two languages differentially as a function of context.

if the

differentiated-language systems hypothesis were true, one would expect to find more frequent use of items from the weaker language in contexts where that language is being used than in contexts where the stronger language is being used, even though items from the stronger language might predominate in both contexts.Слайд 20Genesee et al. 1995

Language differentiation in five bilingual children

prior to the emergence of functional categories

They were observed

with each parent separately and both together, on separate occasions. Results indicate that while these children did code mix, they were clearly able to differentiate between their two languages.

Why only 5?

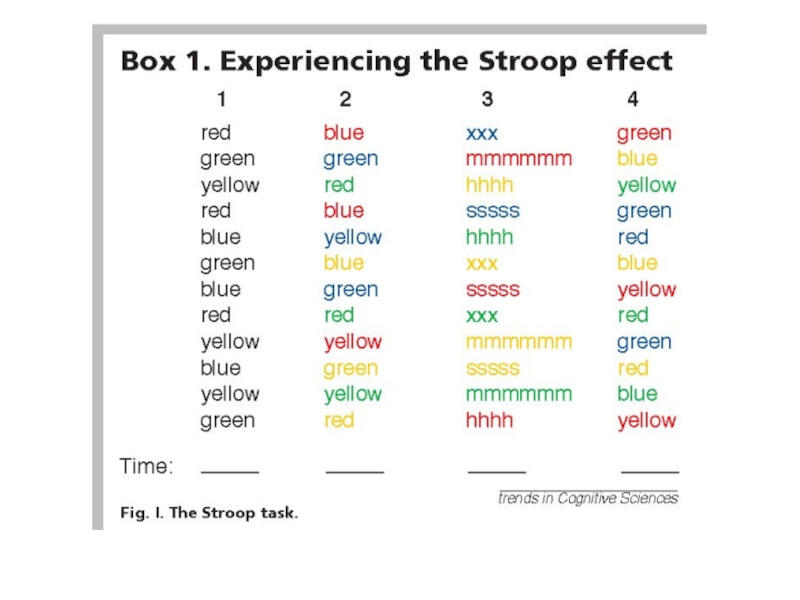

Слайд 21Inhibition theory

Both languages of a bilingual are activated even in

contexts that strongly bias towards only one of them (Kroll

& de Groot, 1997; Grainger, 1993; Guttentag, Haith, Goodman & Hauch, 1984)Press when you see the green square

Press when you see the red square

Слайд 22Press when you see the green square

Press when you see

the red square

congruent case

Press when you see the green square

Press

when you see the red squareincongruent case

Слайд 23Press when you see the green square

Press when you see

the red square

When the case is incongruent, a person tends

to think longer -> the Simon effectСлайд 24Press when you see the green square

Press when you see

the red square

The Simon effect is larger monolinguals

Because bilinguals have

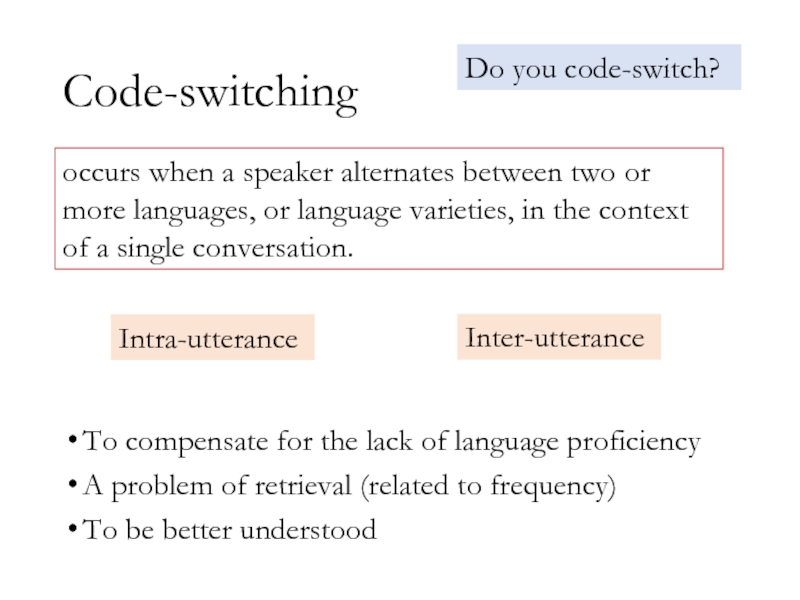

an advantage in inhibitory control (true for children and adults)Слайд 27Code-switching

To compensate for the lack of language proficiency

A problem of

retrieval (related to frequency)

To be better understood

occurs when a speaker

alternates between two or more languages, or language varieties, in the context of a single conversation.Intra-utterance

Inter-utterance

Do you code-switch?

Слайд 28Summary

No evidence to suggest that infants can/should learn only one

language

Simultaneous bilinguals go through the same stages at approximately the

same age as monolingualsBilingual children seem to have 2 language systems

Code-switching is expected

Bilinguals tend to have smaller vocab in one given language than monolinguals even though in total their vocab is bigger

Слайд 30References

Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Green DW, Gollan TH. (2009). Bilingual

minds. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 10, 89–129. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387084.

Bialystok,

E., Luk, G., Peets, K. F., & Yang, S. (2010). Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism (Cambridge, England), 13(4), 525–531. doi:10.1017/S1366728909990423Byers-Heinlein, K., & Werker, J. F. (2009). Monolingual, bilingual, trilingual: Infants’ language experience influences the development of a word learning heuristic. Developmental Science, 12 (5), 815–823.

Eimas, P. D., Siqueland, E. R., Jusczyk, P., & Vigorito, J. (1971). Speech perception in infants. Science, 171(3968), p. 303-306.

Pearson BZ, Fernández SC, Oller DK. (1993). Lexical development in bilingual infants and toddlers: Comparison to monolingual norms. Language Learning, 43:93–120.

Petitto LA, Katerelos M, Levy B, Gauna K, Tétrault K, Ferraro V. (2001). Bilingual signed and spoken language acquisition from birth: Implications for mechanisms underlying bilingual language acquisition. Journal of Child Language, 28:1–44.

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (1984). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life, Infant Behavior and Development, 49-63.