Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Education in great britain

Содержание

- 1. Education in great britain

- 2. Historical BackgroundThe British government attached little importance

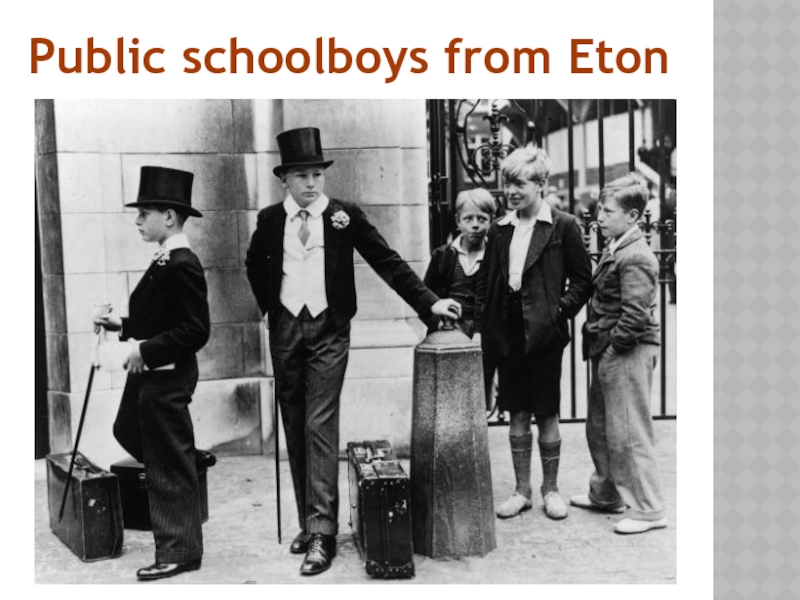

- 3. Public schoolboys from Eton

- 4. When pupils from these schools finished their

- 5. Today. Organization In Britain there is comparatively little

- 6. StyleLearning for its own sake, rather than

- 7. School lifeThere is no countrywide system of

- 8. The school yearSchools usually divide their year

- 9. UniversitiesAfter leaving secondary school young people can

- 10. Cambridge

- 11. FuturePunishments are very unusual for our society.

- 12. When in many countries undisciplined pupils have

- 13. The end

- 14. Скачать презентанцию

Historical BackgroundThe British government attached little importance to education until the end of 19th century. Schools and other educational institutions (such as universities) existed in Britain long before the government began

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 2Historical Background

The British government attached little importance to education until

the end of 19th century.

(such as universities) existed in Britain long before the government began to take an interest in education. When it finally did, it did not sweep these institutions away, nor did it always take them over. In typically British fashion, it sometimes incorporated them into the system and sometimes left them outside it. Most importantly, the government left alone the small group of schools which had been used in 19th century to educate the sons of the upper and upper-middle classes. At these ‘public’ schools the emphasis was on ‘character-building’ and the development of ‘team spirit’ rather than an academic achievement. This involved the development of distinctive customs and attitudes, the wearing of distinctive clothes and the use specialized items if vocabulary. They were all ‘boarding schools’ (that is the pupils lived in them), so they had a deep and lasting influence on their pupils. Their aim was to prepare young men to take up position in the higher ranks of the army, in business, the legal profession, the civil service and politics.Слайд 4When pupils from these schools finished their education, they formed

the ruling elite. They formed a closed group, to a

great extent separate from the rest of society. Entry into this group was difficult for anybody who had had a different education. When, in the 20th century, education and its possibilities for social advancement came within everybody’s reach, new schools tended to copy the features of the public schools. (After all, they provided the only model of a successful school that the country had.Слайд 5Today. Organization

In Britain there is comparatively little central control or

uniformity. For example, education is managed nit by one, but

by three, separate government departments: the Department of education and Employment is responsible for England and Wales alone – Scotland and Northern Ireland have their owns departments. All they do is to ensure the availability of education, dictate and implement its overall organization and set overall learning objectives up to the end of compulsory education. Central government doesn’t prescribe a detailed programme of learning or determine what books and material should be used. It says, in broad terms, what schoolchildren should learn, but it only offers occasional advise about how how they should learn it. It does not manage an institution’s finances either, it just decided how much money to give them. In general, as many details as possible are left up to the individual institution or the Local Education Authority (LEA, a branch of local government) .Слайд 6Style

Learning for its own sake, rather than for any particular

practical purpose, has traditionally been given a comparatively high value

in Britain. British schools and Universities have tended to give such a high priority to sport. The idea is that it helps to develop the ‘complete’ person. People with poor academic records were sometimes accepted as students because of their sporting prowess.Слайд 7School life

There is no countrywide system of nursery schools. In

some areas primary schools have nursery schools attached to them,

but in others there is no provision of this kind. Many children do not begin full-time attendance at school until they are about five and start primary school.Nearly all schools work a five-day week, with no half-day, and are closed on Saturdays. The day starts at or just before 9 o’clock and finishes between three and four, or a bit later for older children. The lunch break usually lasts about an hour-and-a-quarter. Parents pay for it, except for the 15% who are rated poor enough for it to be free. Other children either go home for lunch or take sandwiches. In primary schools, the children are mostly taught by a class teacher who teaches all subjects. At the ages of seven and eleven, children have to take national tests in English, mathematics and science. In secondary schools, pupils have different teaches for different subjects and are given regular homework.

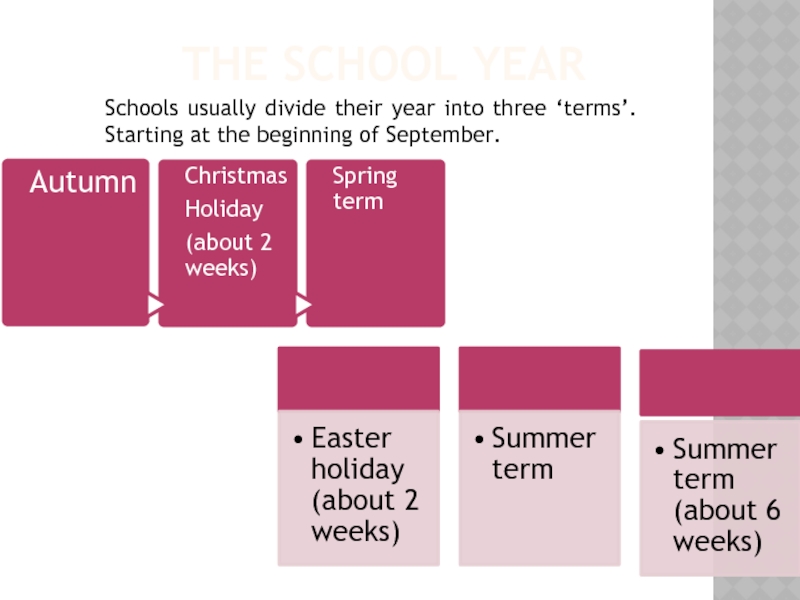

Слайд 8The school year

Schools usually divide their year into three ‘terms’.

Starting at the beginning of September.

Слайд 9Universities

After leaving secondary school young people can apply to a

university, a polytechnic or a college of further education.

There are

126 universities in Britain. They are divided into 5 types:

- The Old ones, which were founded before the 19th century, such as Oxford and Cambridge;

-The Red Brick, which were founded in the 19th or 20th century;

-The Plate Glass, which were founded in 1960s;

-The Open University It is the only university offering extramural education. Students learn subjects at home and then post ready exercises off to their tutors for marking;

The New ones. They are former polytechnic academies and colleges.

The best universities, in view of "The Times" and "The Guardian", are The University of Oxford, The University of Cambridge, London School of Economics, London Imperial College, London University College.

Universities usually select students basing on their A-level results and an interview.

Слайд 11Future

Punishments are very unusual for our society. We can hardly

imagine that children in school might be punished or beaten

because they are undisciplined or do something wrong.But the British Government are going to use hard methods of education including using of physical force…

Слайд 12When in many countries undisciplined pupils have to stand at

lessons, in Britain all children stand. Thus the Ministry of

health decided to attack the problem of obesity.Now they carry out this experiment in some schools but soon it may by a great project in Britain