Слайд 1EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE IN PREGNANCY: clinical histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings

Nurdilda Nargiz, Kani Aidana, Berekekyzy Zhanerke, Bagytzhanova Aina, Sagadinov Sagyndyk

Faculty

of Education and Humanites

Suleyman Demirel University, Kazakhstan

Слайд 2Thanks to ...

Atis Muehlenbachs, Olimpia de la Rosa Vázquez, Daniel

G. Bausch, Ilana J. Schafer, Christopher D. Paddock, Jean Paul

Nyakio, Papys Lame, Eric Bergeron, Andrea M. McCollum, Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Brigid C. Bollweg, Miriam Alía Prieto, Robert Shongo Lushima, Benoit Kebela Ilunga, Stuart T. Nichol, Wun-Ju Shieh, Ute Ströher, Pierre E. Rollin, Sherif R. Zaki

For such great article!

Слайд 3EBOLA VIRUS (EVD)

An infectious

Generally fetal disease marked by

fever

Severe internal

bleeding

Spread throughout contacts with

Body fluids by Filovirus (Ebola Virus)

HOST

Unknown

Named because of Ebola River RIVER

Слайд 5FIRST APPEARANCE OF EVD

In Sudan and Zaire in 1976

FIRST OUTBREAK

In Sudan

Infected over 284 people

Killing 53% of victim

Another

strain appeared

Infected another 318 people

Mortality rate was 86%

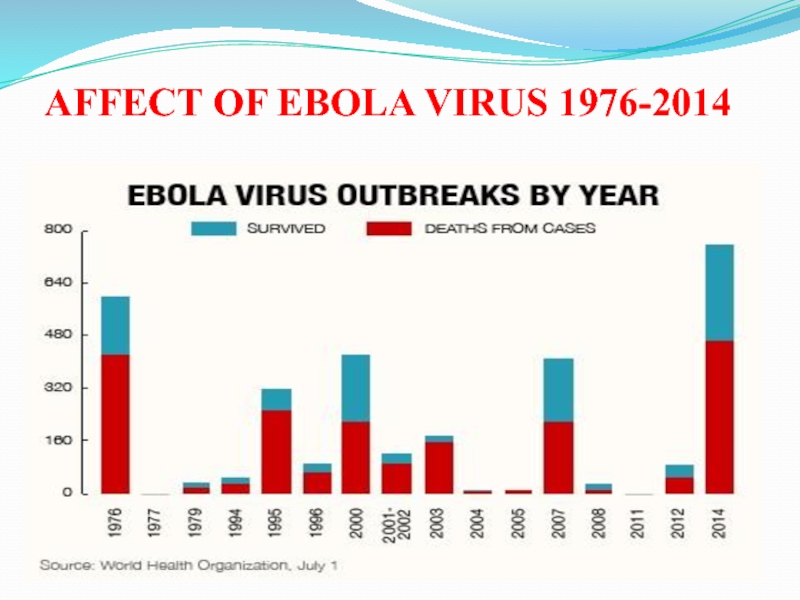

Слайд 6AFFECT OF EBOLA VIRUS 1976-2014

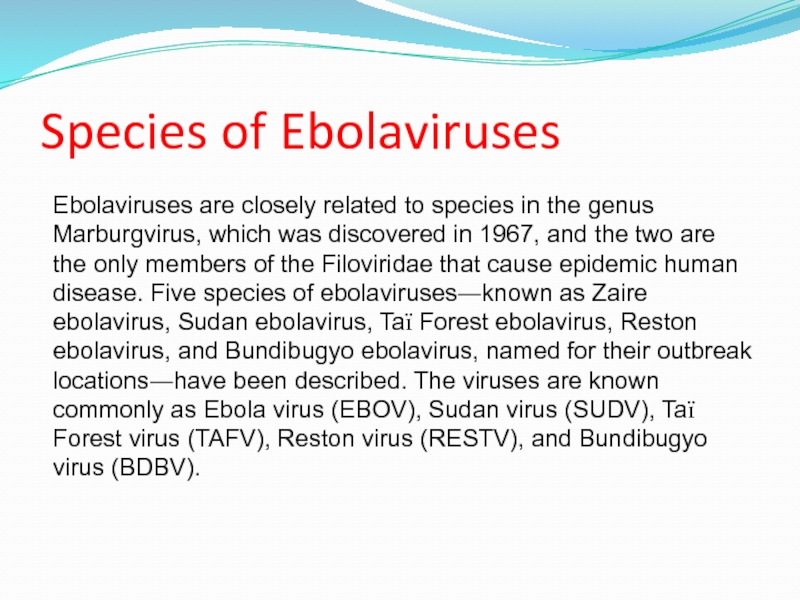

Слайд 7Species of Ebolaviruses

Ebolaviruses are closely related to species in the

genus Marburgvirus, which was discovered in 1967, and the two

are the only members of the Filoviridae that cause epidemic human disease. Five species of ebolaviruses—known as Zaire ebolavirus, Sudan ebolavirus, Taï Forest ebolavirus, Reston ebolavirus, and Bundibugyo ebolavirus, named for their outbreak locations—have been described. The viruses are known commonly as Ebola virus (EBOV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV), Reston virus (RESTV), and Bundibugyo virus (BDBV).

Слайд 8Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Marburg virus disease are caused

by viruses of the Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus genera (family Filoviridae).

Here, we collectively refer to Ebola virus (EBOV), Sudan virus (SUDV) and Bundibugyo virus (BDBV) all within the Ebolavirus genus as ebolaviruses. Filovirus infection during pregnancy is associated with maternal hemorrhage, preterm labor, miscarriage, and maternal and neonatal death. Supplementary Table 1 presents a summary of the scientific literature to date; maternal death occurred in 102 of 125 reported cases (82%), and there was uniform loss of offspring, whether by miscarriage, stillbirth, or neonatal death. Of the 18 live births, the longest survival was 19 days.

Слайд 9Despite the severity of filovirus infection in pregnancy for both

mother and child, very little is known regarding pathogenesis. Fetal-placental

viral tropism has been hypothesized due to recent observations during the 2013–2016 West Africa EBOV outbreak: pregnant women were noted to survive EVD and clear virus from the blood without fetal loss during acute infection and to deliver stillbirths in the subsequent weeks and months with relatively high EBOV RNA levels in placental and fetal tissue swab specimens [7–10]. We report clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical findings of SUDV and BDBV infections in 2 pregnant women and their offspring that help shed light on the pathogenesis of fetal infection and loss in EVD.

Слайд 10METHODS

Patients

Two pregnant women with EVD were cared for in Ebola

treatment centers during ebolavirus outbreaks in Gulu, Uganda, in 2000

[11, 12] and Isiro, DRC, in 2012 [13] (Schafer, unpublished data). Specimens were collected and evaluated during the course of the outbreak responses.

Ebolavirus Diagnostic Testing

SUDV reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) in Gulu and BDBV RT-PCR assays in Isiro were performed as previously described [14, 15] in field laboratories run by the Viral Special Pathogens Branch (VSPB), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, Georgia). BDBV immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) ELISAs were performed by the VSPB in Atlanta.

Слайд 11ELISA

Rapid blood tests detect specific RNA sequences by reverse-transcription polymerase

chain reaction (RT-PCR) or viral antigens by enzyme –linked immunosorbent

assay (ELISA).

Most acute infections are determined through the use of polymerase chain reaction testing (PCR).

Virus is generally detectable by RT-PCR between 3 to 10 days after the onset of symptoms.

Слайд 12Histopathologic Analysis, Immunohistochemical Analysis, and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Placenta (Gulu and

Isiro), fetal tissues (Gulu), and a postmortem skin biopsy (Isiro)

were collected and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and transported to the CDC, where the samples were processed using standard histological methods. The identification and scoring of malarial parasite pigment was performed as previously described [16]. Immunohistochemical analysis for ebolavirus antigens was performed using a polymer-based indirect immunoalkaline phosphatase detection system for colorimetric detection (Biocare Medical, Concord, California). Rabbit polyclonal antisera against EBOV, SUDV, and Reston virus and EBOV hyperimmune mouse ascitic fluid (courtesy of Thomas Ksiazek, VSPB, CDC), previously shown to detect SUDV and BDBV antigens, were each used at a 1:1000 dilution with appropriate positive and negative controls [17]. On-slide embedding and transmission electron microscopy was performed as previously described [18].

Слайд 13RESULTS. Patient 1

Patient 1, Gulu, Uganda, 30-year-old housewife

Symptoms: asthenia, anorexia,

abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and dry cough - presented

with a 1-day of illness. Has been pregnant for 28 weeks. Next day, she had temperature of 36.7°C, here heart rage was 120 beats/minute, and her respiratory rate was 24 breaths/minute, with an oxygen saturation level of 92% by pulse oximetry. Her blood tested positive for SUDV by both ELISA antigen assay and nested RT-PCR.

On day four of illness, the patient spontaneously delivered a dead but apparently morphologically normal fetus and placenta. The degree of vaginal bleeding did not seem abnormal for a stillbirth. Over the next 3 days, the patient complained of joint pain and swelling, throat and chest pain, persistent dry cough, dyspnea, and, briefly, hiccups. Her wrists and knees were visibly swollen and tender to the touch, and pulmonary rales persisted. She was consistently febrile. Disease severity peaked at day 7 of illness, when vital signs were an axillary temperature of 37.8°C, a heart rate of 128 beats/minute, a respiratory rate of 30 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation level of 90%. She gradually improved, and she was discharged on day 13 with normal vital signs and all symptoms resolved.

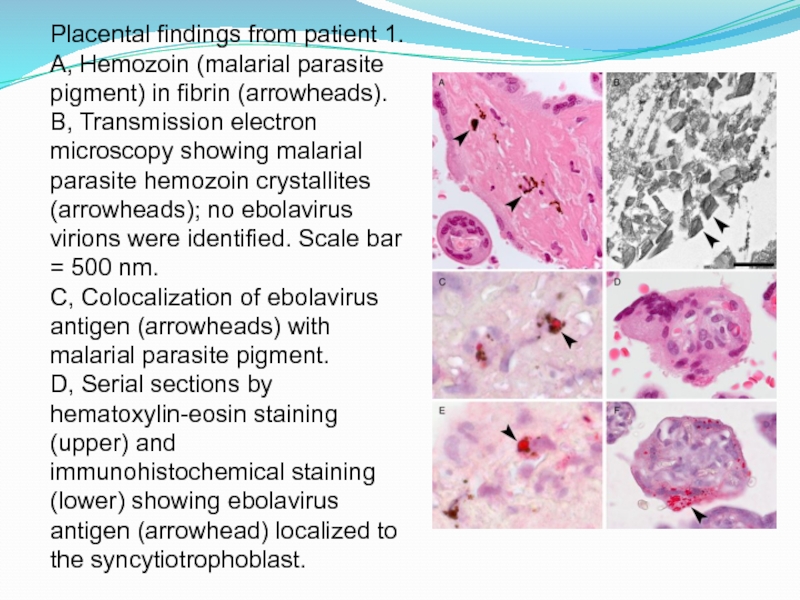

Слайд 14Pathologic Findings

The placenta had mild subchorionitis and a moderate amount

of malarial parasite pigment (hemozoin) in fibrin and within macrophages

embedded in fibrin (Figure 1A). No parasitized erythrocytes or malarial intervillous inflammatory infiltrates were present. By electron microscopy, hemozoin crystallites were identified (Figure 1B), but no ebolavirus virions were seen. The umbilical cord was normal.

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed ebolavirus antigen in the placenta, primarily within areas of fibrin deposition, localized to embedded maternal mononuclear cells, including malarial parasite pigment–laden macrophages (Figure 1C). Focal immunostaining was seen within the syncytiotrophoblast (Figure 1D). The decidua, fetal placental villous stroma, amnion, and umbilical cord were negative by immunohistochemical analysis, and no tissue necrosis or viral inclusions were noted.

Fetal tissues (lung, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, skin, and bone marrow) were well preserved with minimal autolysis, were normal for gestational age, and had no necrosis or viral inclusions. All fetal tissues were negative by immunohistochemical analysis.

Слайд 15Placental findings from patient 1. A, Hemozoin (malarial parasite pigment)

in fibrin (arrowheads). B, Transmission electron microscopy showing malarial parasite

hemozoin crystallites (arrowheads); no ebolavirus virions were identified. Scale bar = 500 nm.

C, Colocalization of ebolavirus antigen (arrowheads) with malarial parasite pigment.

D, Serial sections by hematoxylin-eosin staining (upper) and immunohistochemical staining (lower) showing ebolavirus antigen (arrowhead) localized to the syncytiotrophoblast.

Слайд 16RESULTS. Patient 2

Patient 2, 29-year-old housewife, who was transferred from

a health center because of suspicion of EVD by a

local clinician who was aware that her relative died recently. She was admitted to the Ebola treatment center on day 4 of illness with fever, fatigue, headache, abdominal pain (with uterine contractions), anorexia, dysphagia, vomiting, diarrhea, and muscle and joint pain. Her last menstrual period date was unknown, but she was initially estimated to be 7 months pregnant. Conjunctival injection was noted. Her heart rate was 80 beats/minute, and her respiratory rate was 20 breaths/minute. Her cervix was 50% effaced with a 4-cm dilation, and fetal movement was normal.

On day 5 of illness, her cervix was 100% effaced with an 8-cm dilation, and she was treated with oxytocin. A malaria rapid diagnostic test was positive, and AL was continued. That night (day 6 of illness), spontaneous vaginal delivery of a live-born male infant occurred without assistance. The degree of vaginal bleeding did not seem abnormal for a normal delivery, although she had had an episode of black stool some hours later. She was treated with oxytocin, ergometrine, intravenous fluids, and cefixime, and Plumpy′nut (Nutriset) was provided. On day 7, the mother's condition rapidly deteriorated, with wheezing, drowsiness, weakness, and a temperature of 38.5°C. Antibiotics were switched to ceftriaxone. On day 8, she became comatose and died. A postmortem skin sample was collected from the mother as part of the routine outbreak response protocol [17].

Слайд 17The infant appeared healthy at birth, with Apgar scores of

8/10/10, and was clinically assessed to be at term on

the basis of examination of the nails and soles of the feet. Infant formula was provided, although the baby may have briefly breastfed immediately after delivery. A placental sample was collected to evaluate for BDBV. Blood collected at 1 day of age (the second day of life) was positive for BDBV by RT-PCR, with a cycle threshold (Ct) of 29.2. Over the next few days, the baby was noted to be quiet and inactive. He became febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) on day 4 of age, and repeat testing of the blood revealed an RT-PCR Ct of 17.9 with negative IgM and IgG ELISA results. Over the next few days, the baby had hematemesis and bloody stools. He developed respiratory distress and coma and died on the seventh day of age (eighth day of life). No postmortem specimens were collected from the infant.

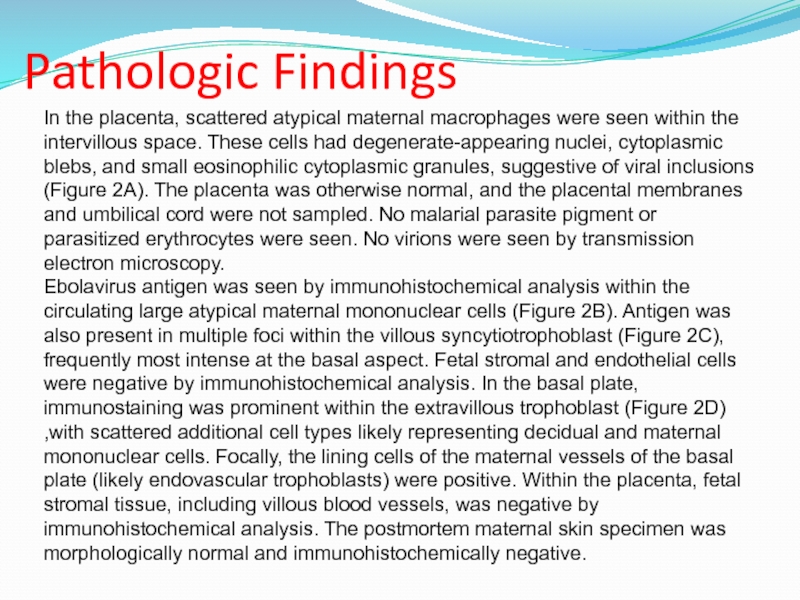

Слайд 18Pathologic Findings

In the placenta, scattered atypical maternal macrophages were seen

within the intervillous space. These cells had degenerate-appearing nuclei, cytoplasmic

blebs, and small eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules, suggestive of viral inclusions (Figure 2A). The placenta was otherwise normal, and the placental membranes and umbilical cord were not sampled. No malarial parasite pigment or parasitized erythrocytes were seen. No virions were seen by transmission electron microscopy.

Ebolavirus antigen was seen by immunohistochemical analysis within the circulating large atypical maternal mononuclear cells (Figure 2B). Antigen was also present in multiple foci within the villous syncytiotrophoblast (Figure 2C), frequently most intense at the basal aspect. Fetal stromal and endothelial cells were negative by immunohistochemical analysis. In the basal plate, immunostaining was prominent within the extravillous trophoblast (Figure 2D) ,with scattered additional cell types likely representing decidual and maternal mononuclear cells. Focally, the lining cells of the maternal vessels of the basal plate (likely endovascular trophoblasts) were positive. Within the placenta, fetal stromal tissue, including villous blood vessels, was negative by immunohistochemical analysis. The postmortem maternal skin specimen was morphologically normal and immunohistochemically negative.

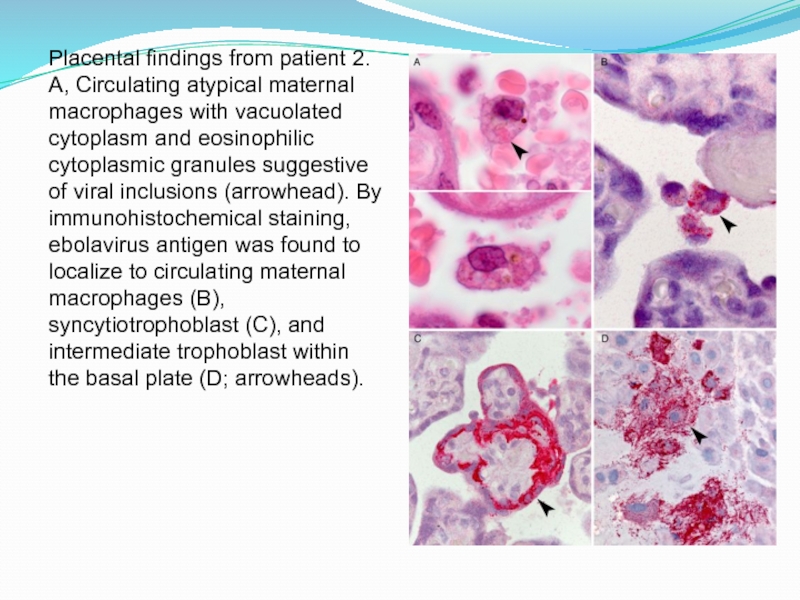

Слайд 19Placental findings from patient 2. A, Circulating atypical maternal macrophages

with vacuolated cytoplasm and eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules suggestive of viral

inclusions (arrowhead). By immunohistochemical staining, ebolavirus antigen was found to localize to circulating maternal macrophages (B), syncytiotrophoblast (C), and intermediate trophoblast within the basal plate (D; arrowheads).

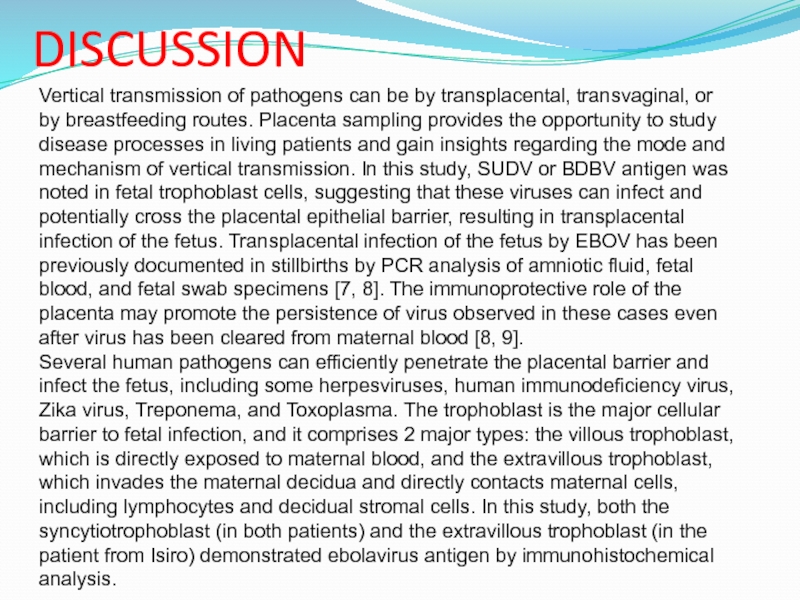

Слайд 20DISCUSSION

Vertical transmission of pathogens can be by transplacental, transvaginal, or

by breastfeeding routes. Placenta sampling provides the opportunity to study

disease processes in living patients and gain insights regarding the mode and mechanism of vertical transmission. In this study, SUDV or BDBV antigen was noted in fetal trophoblast cells, suggesting that these viruses can infect and potentially cross the placental epithelial barrier, resulting in transplacental infection of the fetus. Transplacental infection of the fetus by EBOV has been previously documented in stillbirths by PCR analysis of amniotic fluid, fetal blood, and fetal swab specimens [7, 8]. The immunoprotective role of the placenta may promote the persistence of virus observed in these cases even after virus has been cleared from maternal blood [8, 9].

Several human pathogens can efficiently penetrate the placental barrier and infect the fetus, including some herpesviruses, human immunodeficiency virus, Zika virus, Treponema, and Toxoplasma. The trophoblast is the major cellular barrier to fetal infection, and it comprises 2 major types: the villous trophoblast, which is directly exposed to maternal blood, and the extravillous trophoblast, which invades the maternal decidua and directly contacts maternal cells, including lymphocytes and decidual stromal cells. In this study, both the syncytiotrophoblast (in both patients) and the extravillous trophoblast (in the patient from Isiro) demonstrated ebolavirus antigen by immunohistochemical analysis.

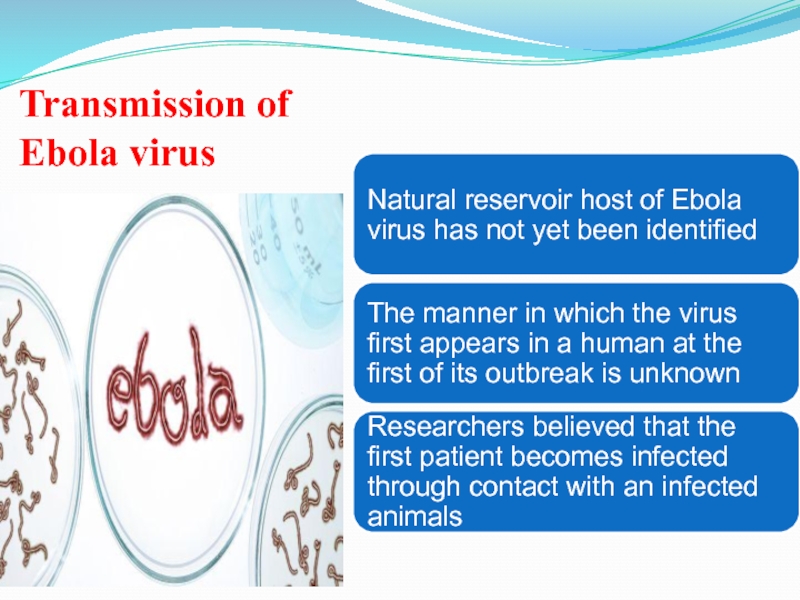

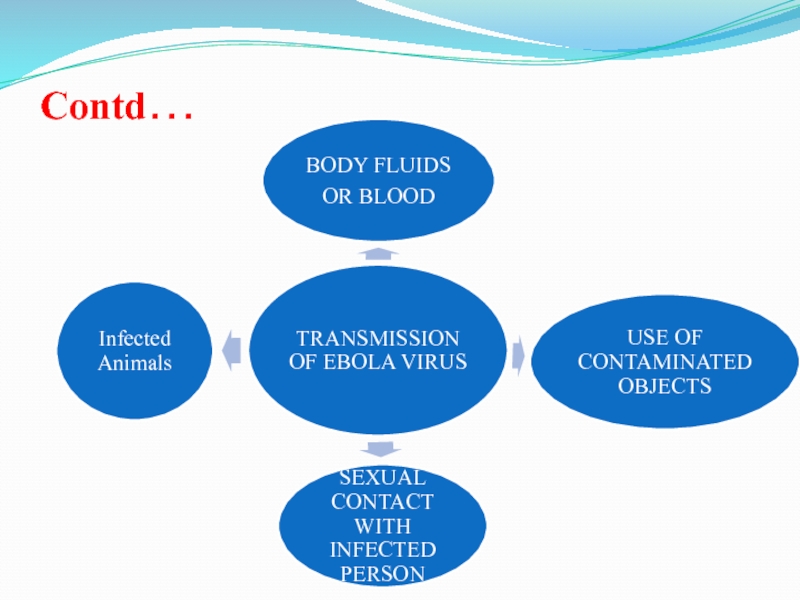

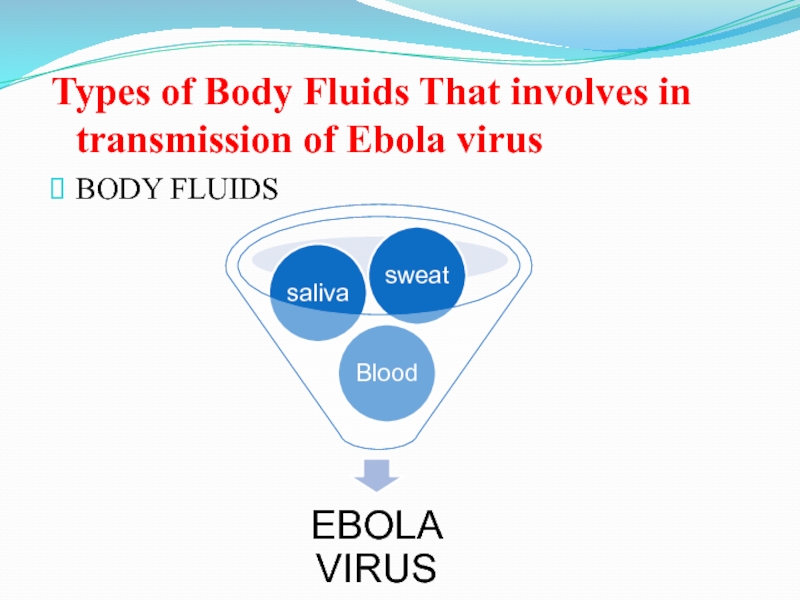

Слайд 24

Types of Body Fluids That involves in transmission of Ebola

virus

BODY FLUIDS

Слайд 26CONTAMINATED OBJECTS THROUGH WHICH EBOLA VIRUS TRANSMITS

Слайд 27IN AFRICA,EBOLA VIRUS MAY BE SPREAD THROUGH BUSHMEAT

Слайд 28

TRADITIONAL AFRICAN RITUALS PLAYED ROLE IN TRANSMISSION OF VIRUS

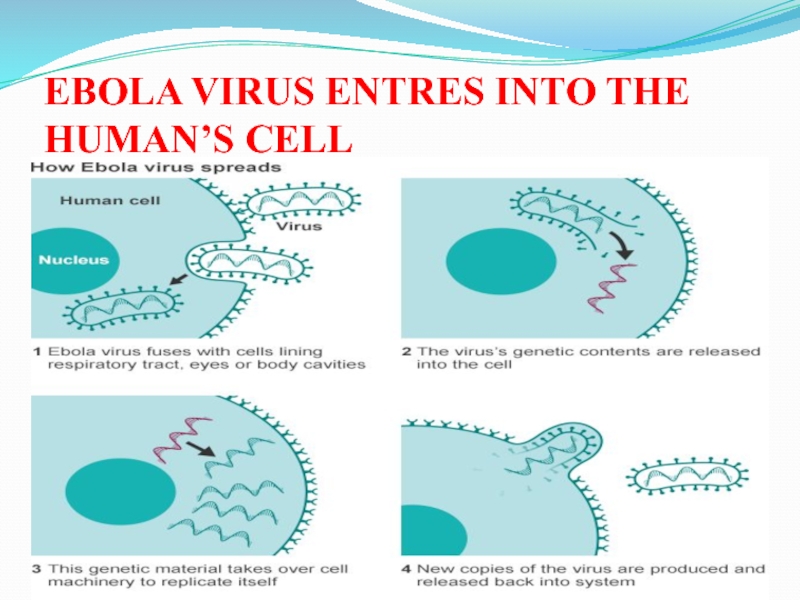

Слайд 29EBOLA VIRUS ENTRES INTO THE HUMAN’S CELL

Слайд 30OTHER WAYES IN WHICH EBOLA VIRUS CAN TRANSMIT

Слайд 31

EBOLA VIRUS VICTIM’S BODY BURNED ON HUGE FUNERAL PYRE IN

DESPERATE BATTLE TO STOP OUTBREAK

MASS CREMATION HAVE BEEN

SANCTIONED BY THE GOVERNMENT IN LIBERIA IN BID TO HELP TO HALT THE DEADLY VIRUS

Слайд 32THESE SHOCKING PICTURES SHOW THE BODIES OF EBOLA VICTIMS BEING

BURNED ON HUGE FUNERAL PYRE

Слайд 33FRUIT BATS ARE MAJOR CAUSE FOR THE TRANSMISSION OF THE

EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE

Слайд 34UNHYGIENIC ENVIRONMENT MAY ALSO BE A CAUSE OF TRANSMISSION OF

EBOLA VIRUS IN WEST AFRICA

Слайд 35CDC WORKER INCINERATES MEDICAL WASTE FROM EBOLA PATIENTS IN ZAIRE

Слайд 38 Early signs and symptoms of infections (7-9 Days)

FEVER

If there

is no fever there is no Ebola.

Слайд 39HEADACHE

Severe headaches start developing

Слайд 40NAUSEA

Sickness in the stomach

and involuntarily impulse

to vomit is

felt by patient.

Слайд 41

MUSCULAR PAIN

Joint and muscle pain leads to intense weakness

throughout the body of the person.

Слайд 44Day 10th followed by:

Vomiting

An another major

symptom to

approve the

person

is infected

by Ebola virus.

Слайд 47Condition worsens on day 11th

BRAIN DAMAGE

Loss of consciousness ,

Seizures,

Massive

internal bleeding

leads to brain damage.

Слайд 48Internal & External Bleeding

Bleeding from body

Openings (nose, gums ,gastrointestinal

tract, etc) may be seen

In some patients.

Слайд 49Diagnosis Of Ebola Virus

How it is diagnosed?

Слайд 50Diagnosis before testing is completed for Ebola, test for following

disease must be completed

Malaria

Typhoid fever

Shigellosis

Cholera

Leptospirosis

Rickettsiosis

Relapsing fever

Meningitis

Hepatitis

Other viral hemorrhagic fevers

Слайд 51It is difficult to distinguish EVD from other infectious diseases

but it can be investigated by some methods

Antibody-capture enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Antigen-capture detection tests

Serum neutralization test

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

(RT-PCR) assay

Electron microscopy

Virus isolation by cell culture

Слайд 52Diagnostic Considerations

Although there is no approved specific therapy for Ebola

virus.

Clinical Findings - include fever of greater than 36.8 C

(101.5 F) and additional signs or symptoms like severe headache, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain

Risk factors

Those who have had contact with blood, body fluids or human remains of a patient known to have or suspected to have Ebola virus disease.

Residence in or travel to an area where Ebola virus transmission is active.

Direct handling of bats, rodents or primates from endemic areas.

Слайд 53A high risk exposure includes any of the following

Percutaneous or

mucous membrane exposure to blood or body fluids of a

person with Ebola virus disease.

Direct skin contact with patient having Ebola virus disease without appropriate personal protective equipment.

Direct contact with dead body without personal safety equipments in a country where an Ebola virus disease outbreak is occurring.

Слайд 54Diagnostic Tests

Rapid blood tests for Marburg and Ebola virus infection

are the most commonly used tests for diagnosis.

Testing for

Ebola and Marburg virus should only be performed in specialized laboratories.

Слайд 55Other Tests

Antigen detection may be used as a confirmatory test

for immediate diagnosis.

For individuals, who are recovering from Ebola virus

disease, PCR testing is also used to determine when a patient can be discharged from hospital setting.

In some cases, testing for IgM or IgG antibodies to Ebola virus may also be useful to monitor the immune response over time and/or evaluate for past infection.

Слайд 56Stages of symptoms of Ebola virus

Stage 1

Headache, sore

throat, fever, muscle soreness

Stage 2

High fever, Vomiting, Passive

Behaviour

Stage 3

Bruising, Bleeding from nose, mouth, eyes;

Blood in stool, Impaired liver function

Stage 4

Loss of consciousness, Seizures, Internal bleeding leading to death

Слайд 57Hospital Protocol for Ebola hit

Handling Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Removal

Isolation

Fluid Control

Disinfecting

No

Needles

Слайд 58A new drug target for Ebola virus

Researchers have recently developed

a new drug target in the Ebola virus that could

be used against it to fight the disease

University of Utah chemists have produced a molecule known as peptide mimic that displays a functionally critical region of the virus that is universally conserved in all known species of Ebola

Слайд 59TREATMENT AND VACCINE FOR EBOLA VIRUS

Coffee, Fermented Soy, homeopathic

Spider Venom, And

Vitamin C, May All Hold

Promise As Anti Ebola Virus

Therapies.

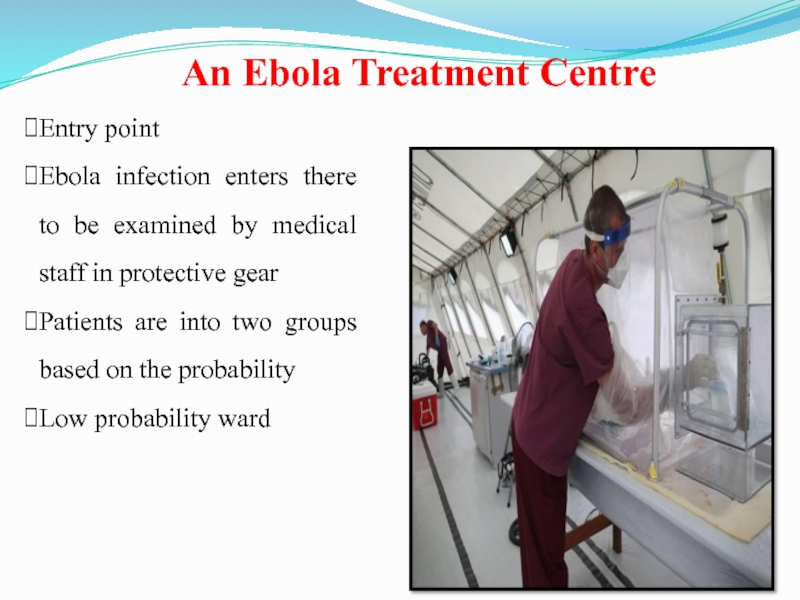

Слайд 60Entry point

Ebola infection enters there to be examined by

medical staff in protective gear

Patients are into two groups

based on the probability

Low probability ward

An Ebola Treatment Centre

Слайд 61Patients could face a long wait until their test results

from the lab come back, revealing whether or not they

are infected . Patients who might not have the deadly virus are isolated from those suffering from Ebola , reducing their exposure to the infection while In the treatment centre.

Слайд 62Patients suspected of having Ebola based on the initial medical

examination remain here until official confirmation arrives that they have

the virus . Only once the Ebola diagnosis is confirmed they transferred to another ward

High Probability Ward

Слайд 63Decontamination

The Utah scientists designed peptide mimic of a highly conserved

region in the Ebola protein that controls entry of the

virus into the human host cells.

Dressing Room

Dressing for a high risk area is a complex process. Medicals walk in a pairs , with the partner checking for any tears in the suit .

The protective equipment includes a surgical cap and hood ,gogles , medical mask ,impermeable overalls ,an apron ,two sets of gloves and rubber boots

Слайд 64Mortuary

The mortuary is located outside the clinic but within the

double fence as bodies are highly infectious .

Patient Exit

The exit on the side are for patients whose blood tests show that they do not have ebola ,or those that recover.

Слайд 65

Statins should be considered as a possible treatment for Ebola

Statins

also have been suggested as a treatment for patient with

sepsis, a condition that involves an out of control immune response similar to that seen in Ebola patients.

Could Statins Treat Ebola

Слайд 66Experimental Canadian made Ebola vaccine is beginning clinical trials in

healthy humans .

The results are expected in December

Clinical trails are

now starting for an experimental made in Canada Ebola vaccine amid growing global concern over the disease that’s left more than 4,000 people dead.

Canadian – Made Ebola Vaccine Starting Clinical Trials In Humans

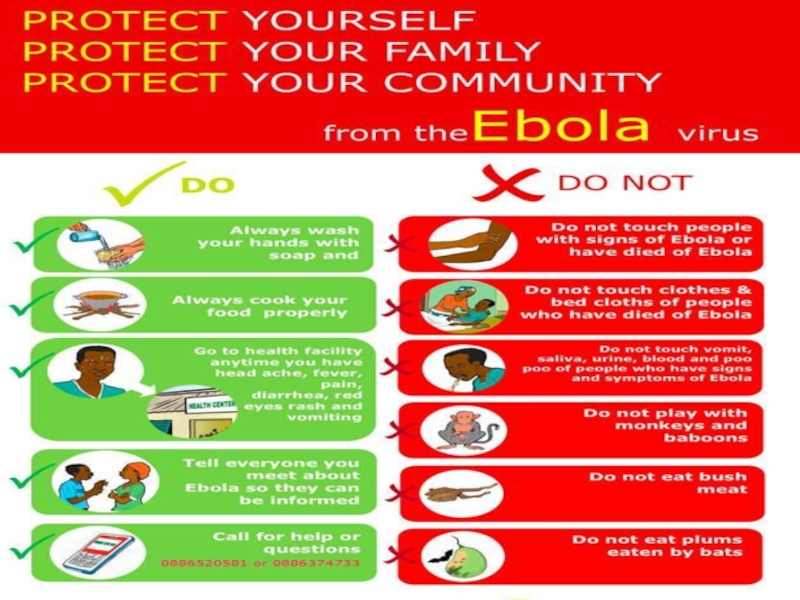

Слайд 68If have sudden fever, diarrhoea, or vomiting, go to the

nearest health facility

Make no contact with Ebola affected people

Use a

special kind of clothes while treating Ebola affected people

HOW TO PREVENT EVD

Слайд 70

QUICK ACCESS TO APPROPRIATE LABORATORY SERVICES

Слайд 71PROPER MANAGEMENT SERVICES FOR WHO ARE INFECTED

Слайд 72PROPER DISPOSAL OF DEAD THROUGH CREMATION OR BURIAL

Слайд 73WORLDWIDE HELPLINE NUMBER

People who go early to the health centre

have a better chance of survival.

CALL 117 WITH YOUR QUESTIONS