Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

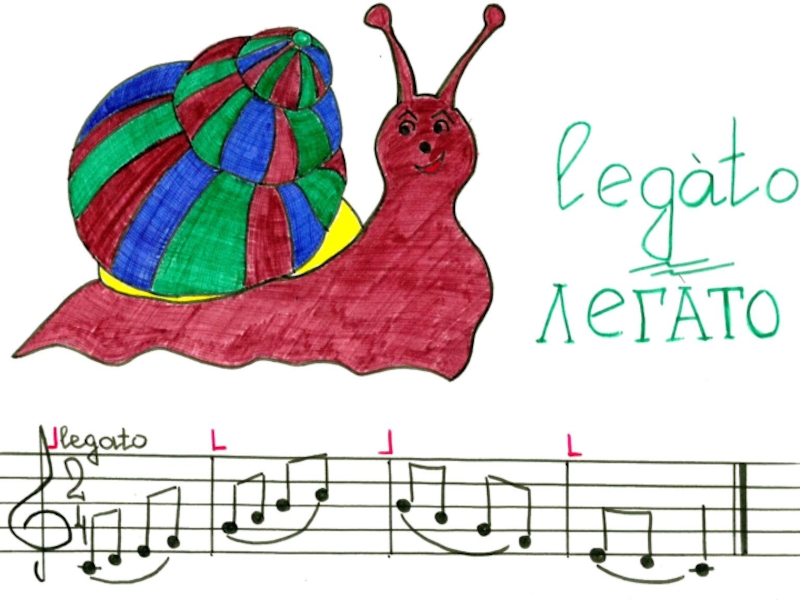

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Machine-Level Programming I: Basics 15-213/18-213 : Introduction to Computer

Содержание

- 1. Machine-Level Programming I: Basics 15-213/18-213 : Introduction to Computer

- 2. Office HoursNot too well attended (yet?)Ask your

- 3. Today: Machine Programming I: BasicsHistory of Intel

- 4. Intel x86 ProcessorsDominate laptop/desktop/server marketEvolutionary designBackwards compatible

- 5. Intel x86 Evolution: Milestones Name Date Transistors MHz8086 1978 29K 5-10First 16-bit Intel processor.

- 6. Intel x86 Processors, cont.Machine Evolution386 1985 0.3M Pentium 1993 3.1MPentium/MMX 1997 4.5MPentiumPro 1995 6.5MPentium III 1999 8.2MPentium 4 2000 42MCore

- 7. Intel x86 Processors, cont.Past Generations1st Pentium Pro 1995 600

- 8. 2018 State of the Art: Skylake (Core

- 9. x86 Clones: Advanced Micro Devices (AMD)HistoricallyAMD has

- 10. Intel’s 64-Bit History2001: Intel Attempts Radical Shift

- 11. Our CoverageIA32The traditional x86For 15/18-213: RIP, Summer

- 12. Today: Machine Programming I: BasicsHistory of Intel

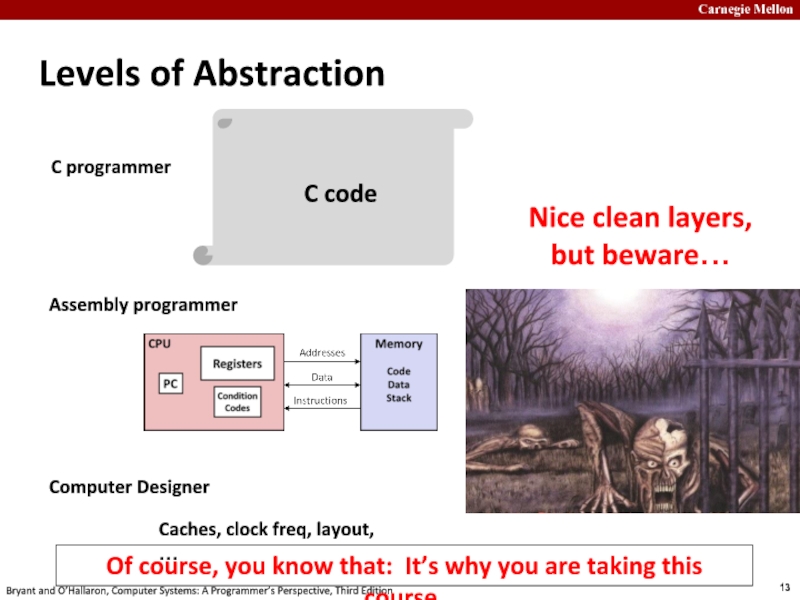

- 13. Levels of AbstractionC programmerAssembly programmerComputer DesignerC codeCaches,

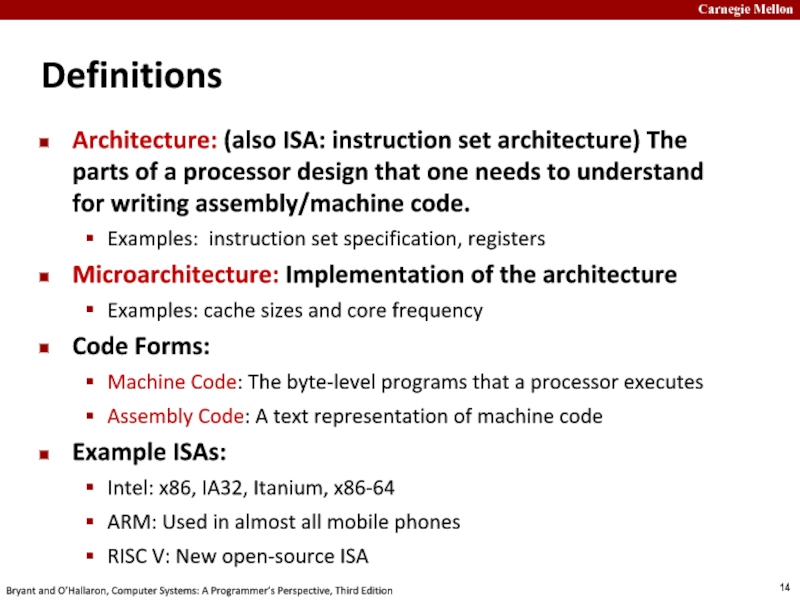

- 14. DefinitionsArchitecture: (also ISA: instruction set architecture) The

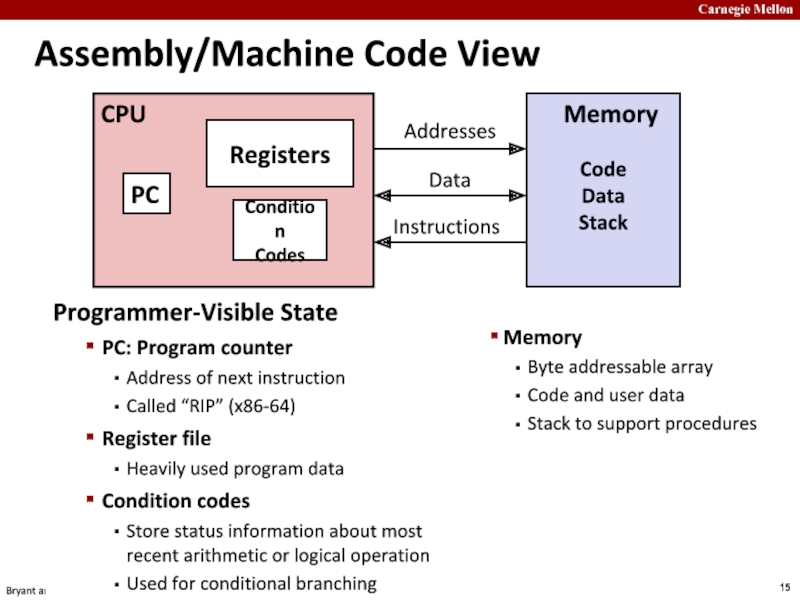

- 15. CPUAssembly/Machine Code ViewProgrammer-Visible StatePC: Program counterAddress of

- 16. Assembly Characteristics: Data Types“Integer” data of 1,

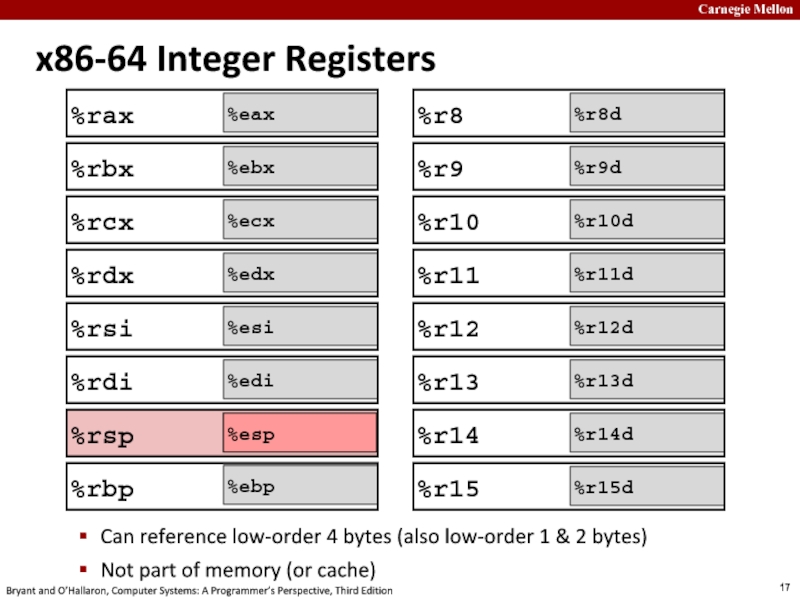

- 17. %rspx86-64 Integer RegistersCan reference low-order 4 bytes

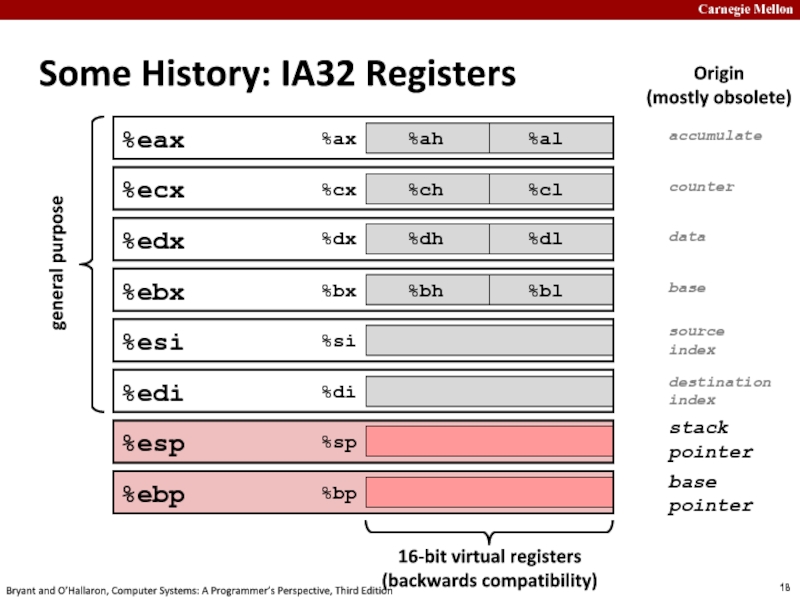

- 18. Some History: IA32 Registers%ax%cx%dx%bx%si%di%sp%bp%ah%ch%dh%bh%al%cl%dl%bl16-bit virtual registers(backwards compatibility)general purposeaccumulatecounterdatabasesource indexdestinationindexstack pointerbasepointerOrigin(mostly obsolete)

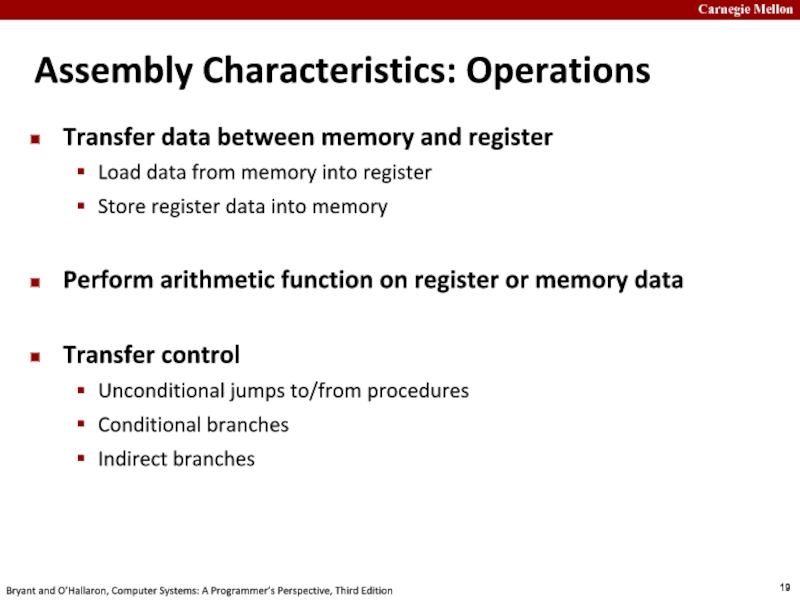

- 19. Assembly Characteristics: OperationsTransfer data between memory and

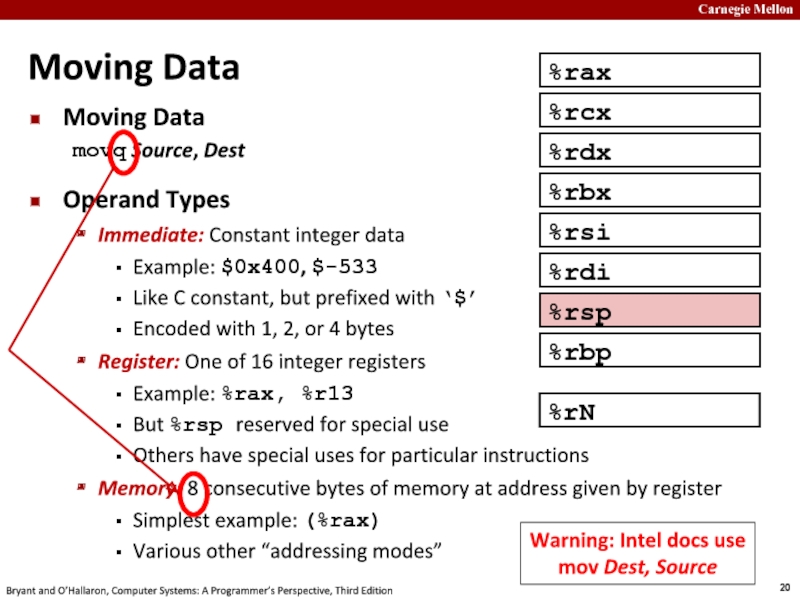

- 20. Moving DataMoving Datamovq Source, DestOperand TypesImmediate: Constant

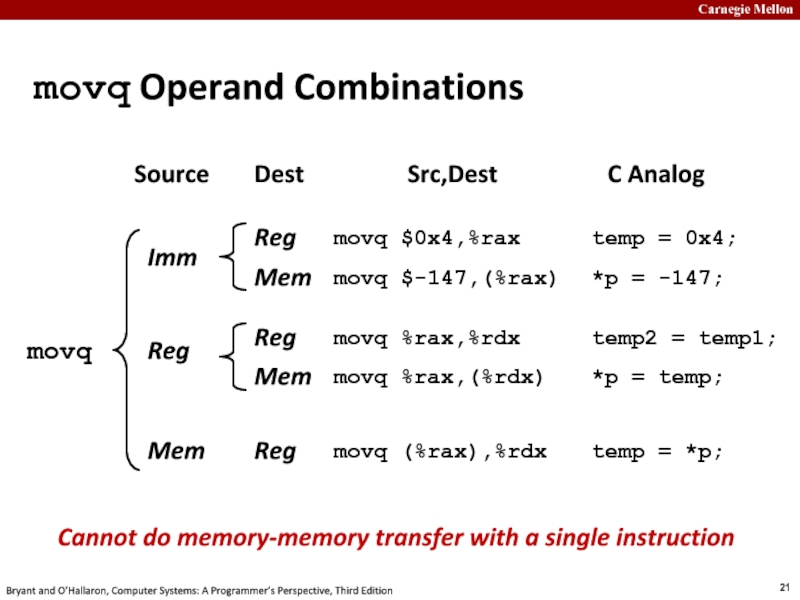

- 21. movq Operand CombinationsCannot do memory-memory transfer with

- 22. Simple Memory Addressing ModesNormal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]Register R specifies memory

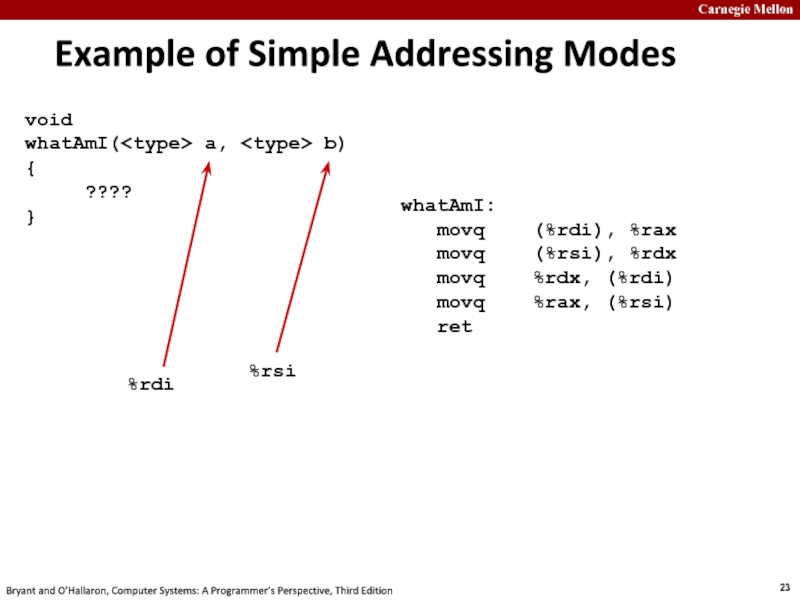

- 23. Example of Simple Addressing ModeswhatAmI: movq

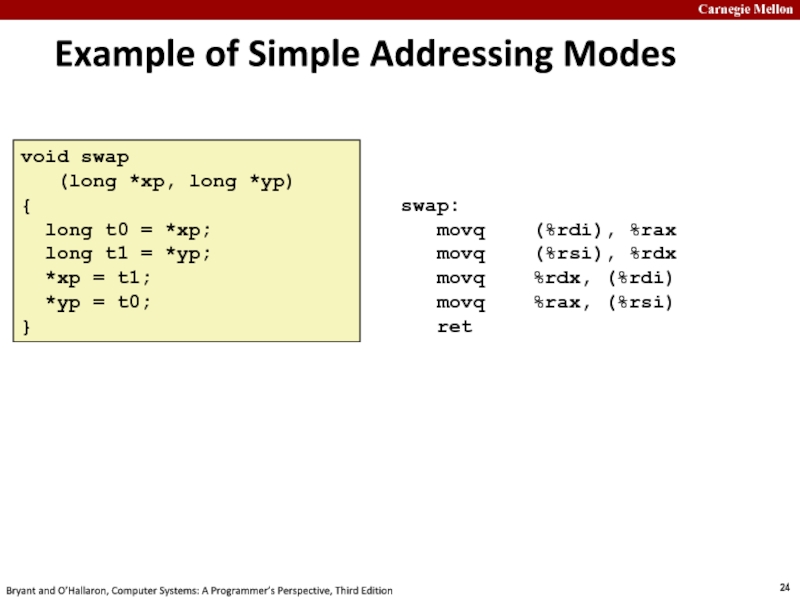

- 24. Example of Simple Addressing Modesvoid swap

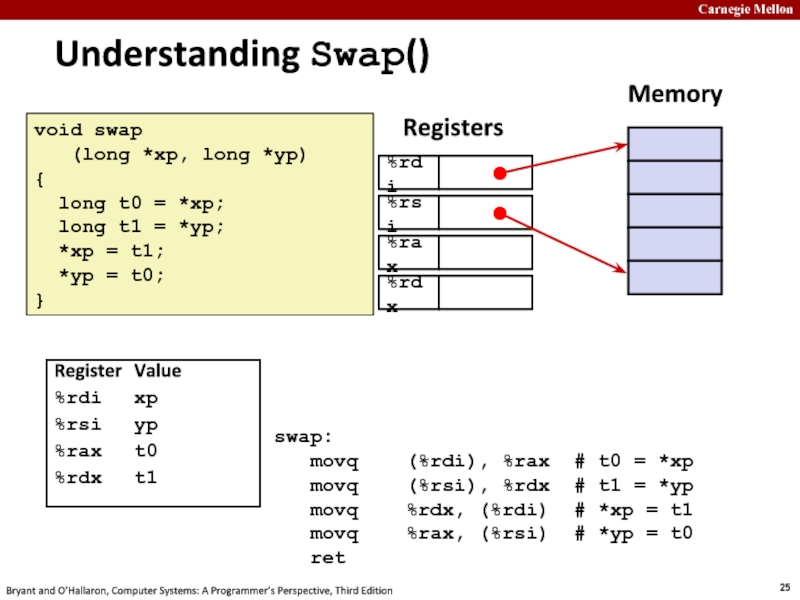

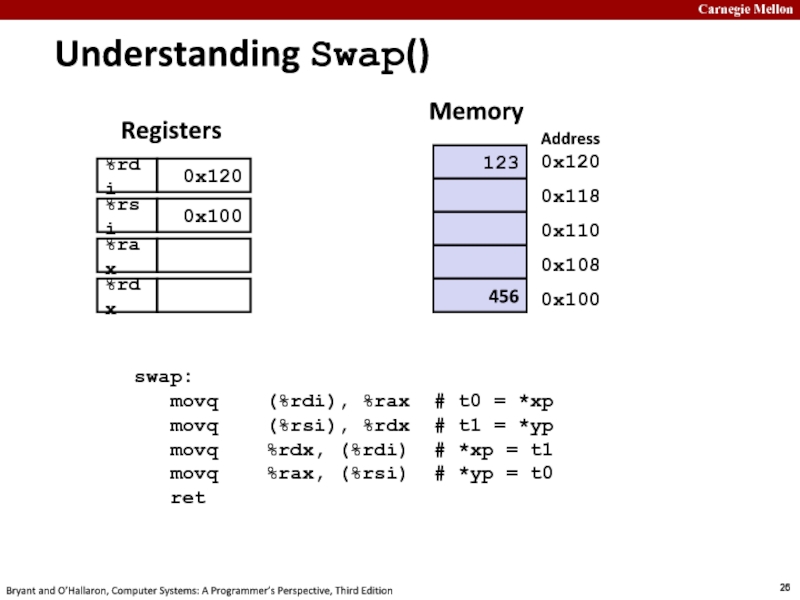

- 25. Understanding Swap()void swap (long *xp, long

- 26. Understanding Swap()123456RegistersMemoryswap: movq (%rdi), %rax

- 27. Understanding Swap()123456RegistersMemoryswap: movq (%rdi), %rax

- 28. Understanding Swap()123456RegistersMemoryswap: movq (%rdi), %rax

- 29. Understanding Swap()456456RegistersMemoryswap: movq (%rdi), %rax

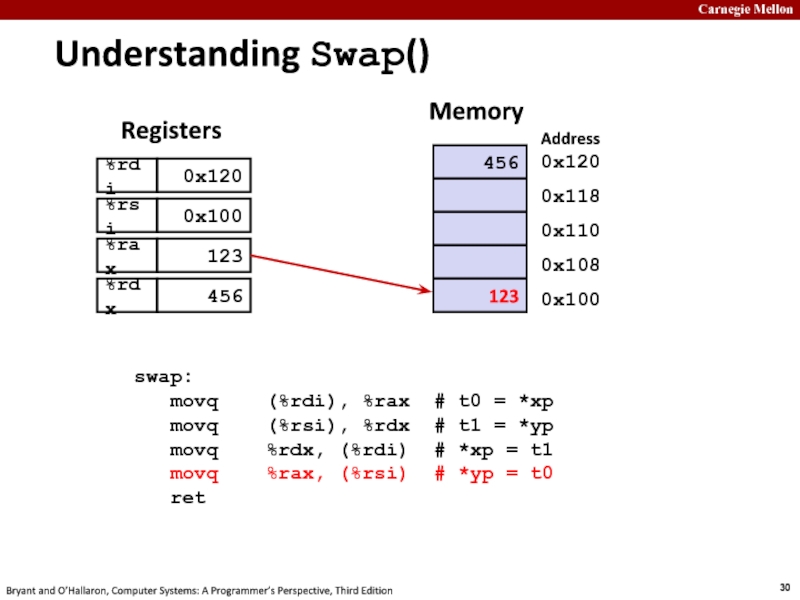

- 30. Understanding Swap()456123RegistersMemoryswap: movq (%rdi), %rax

- 31. Simple Memory Addressing ModesNormal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]Register R specifies memory

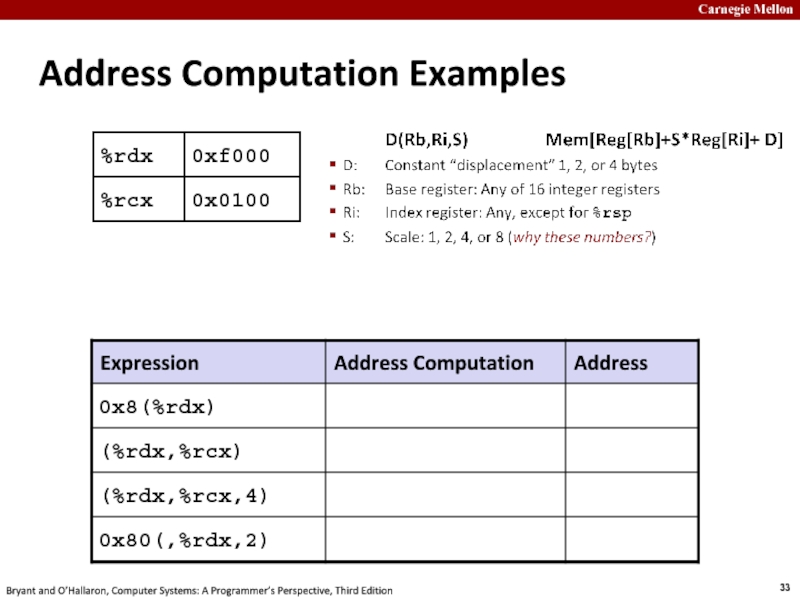

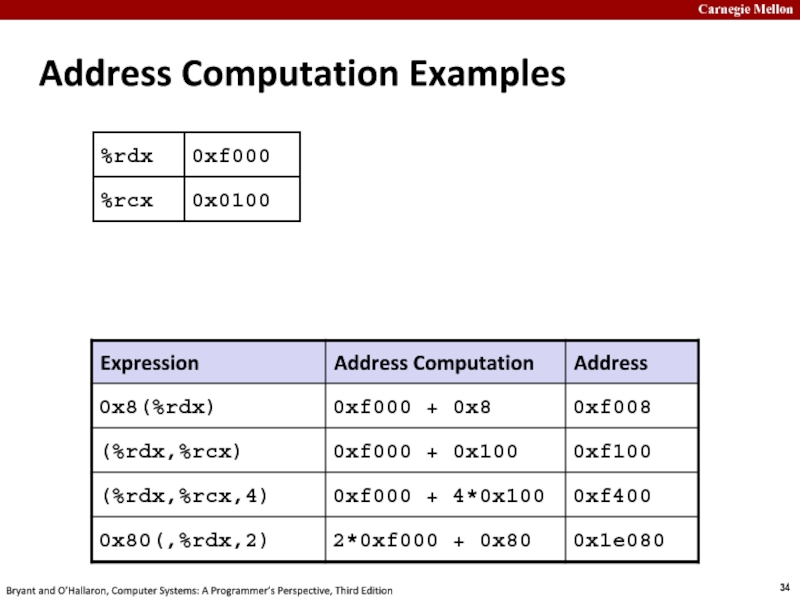

- 32. Complete Memory Addressing ModesMost General Form D(Rb,Ri,S) Mem[Reg[Rb]+S*Reg[Ri]+ D]D:

- 33. Address Computation Examples

- 34. Address Computation Examples

- 35. Today: Machine Programming I: BasicsHistory of Intel

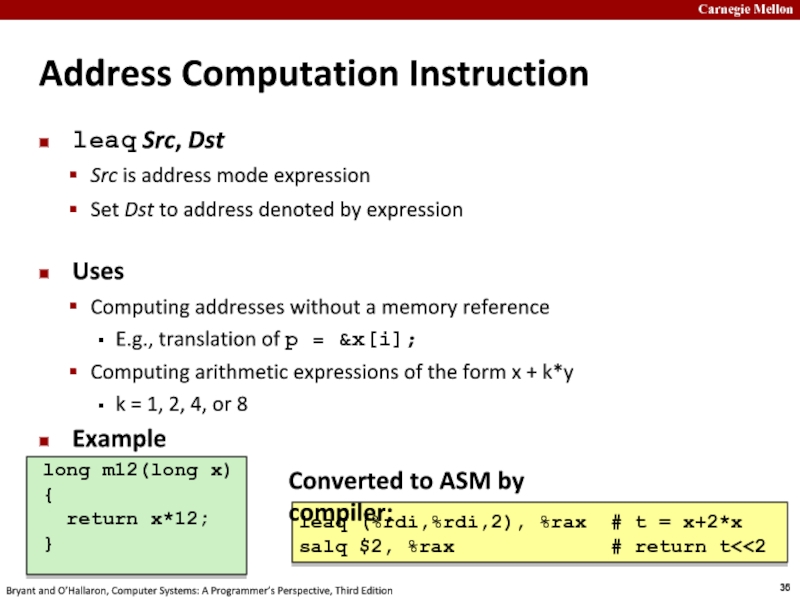

- 36. Address Computation Instructionleaq Src, DstSrc is address

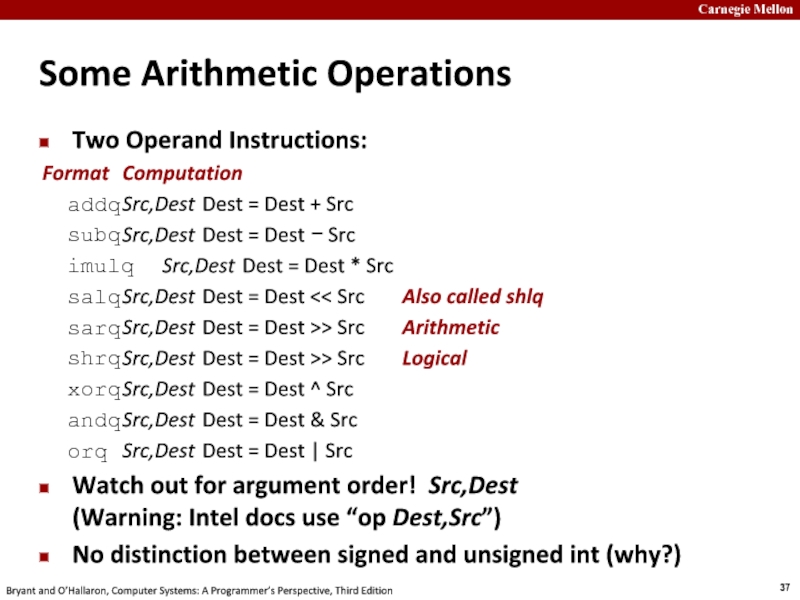

- 37. Some Arithmetic OperationsTwo Operand Instructions:Format Computationaddq Src,Dest Dest = Dest

- 38. Quiz Time! halblustig: German, literal translation: “semi-funny”

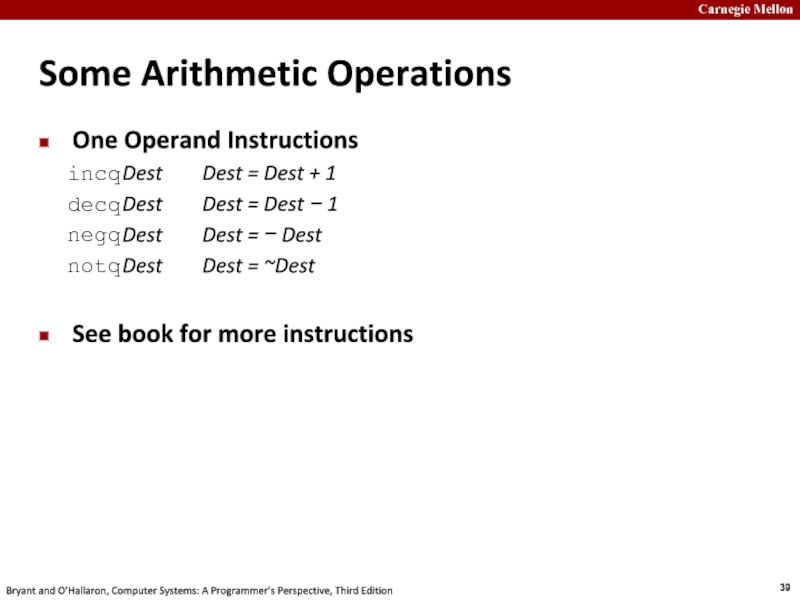

- 39. Some Arithmetic OperationsOne Operand Instructionsincq Dest Dest = Dest

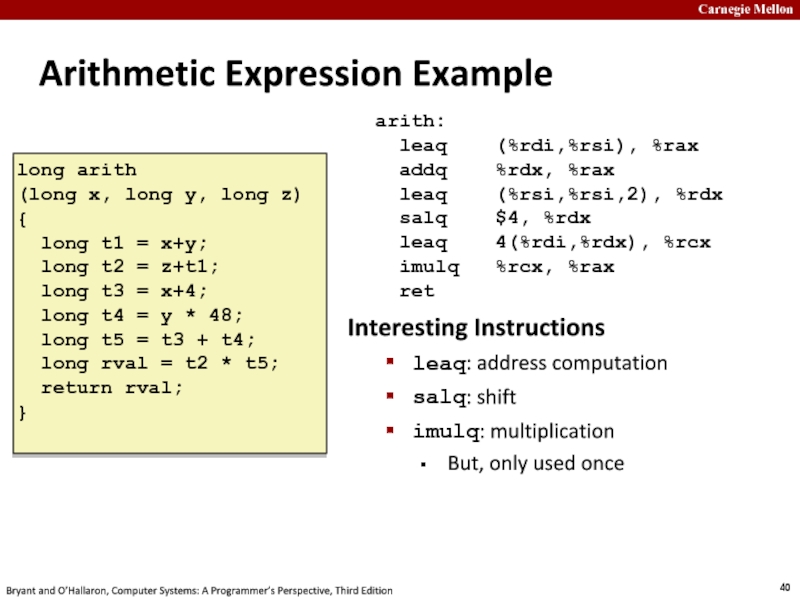

- 40. Arithmetic Expression ExampleInteresting Instructionsleaq: address computationsalq: shiftimulq:

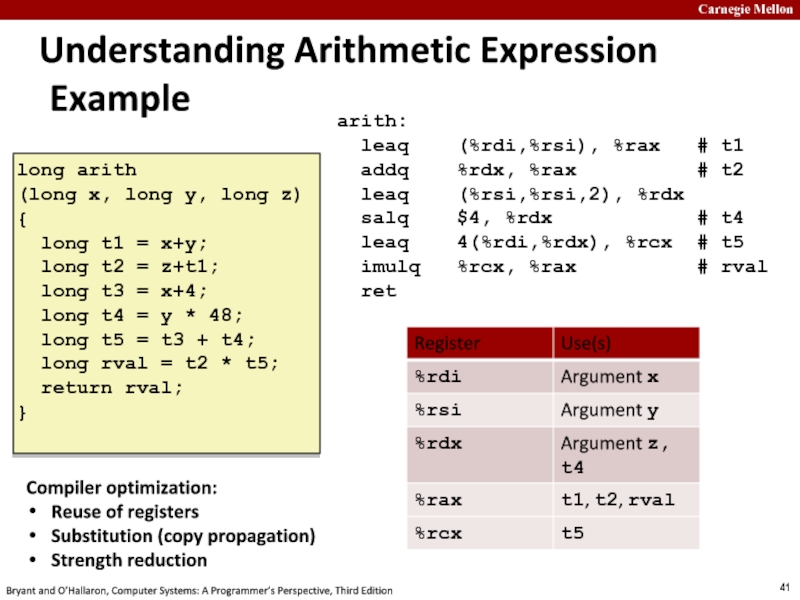

- 41. Understanding Arithmetic Expression Examplelong arith(long x, long

- 42. Today: Machine Programming I: BasicsHistory of Intel

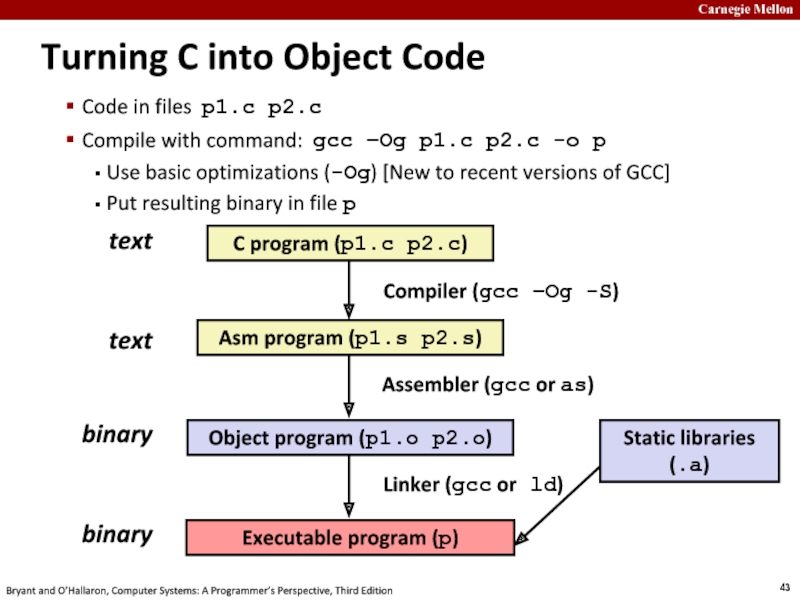

- 43. texttextbinarybinaryCompiler (gcc –Og -S)Assembler (gcc or as)Linker

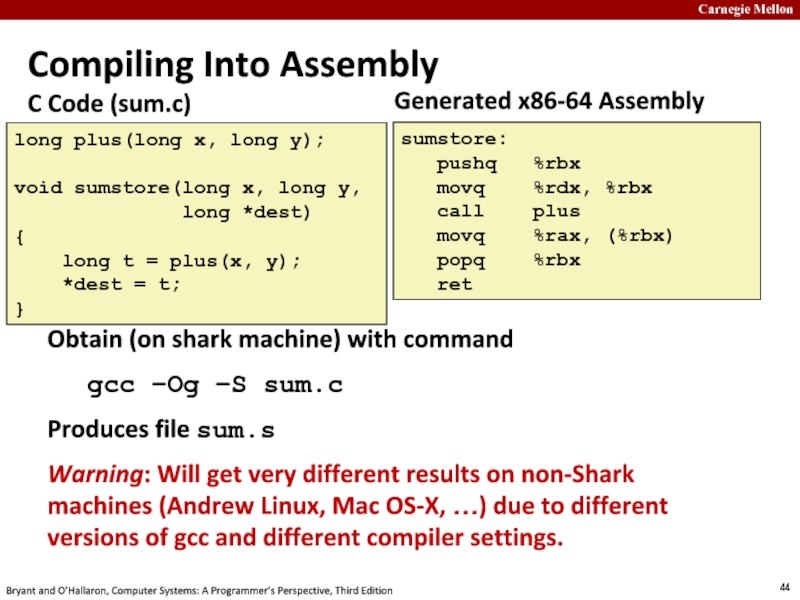

- 44. Compiling Into AssemblyC Code (sum.c)long plus(long x,

- 45. What it really looks like .globl sumstore .type sumstore, @functionsumstore:.LFB35: .cfi_startproc pushq %rbx .cfi_def_cfa_offset 16 .cfi_offset 3, -16 movq %rdx, %rbx call plus movq %rax, (%rbx) popq %rbx .cfi_def_cfa_offset 8 ret .cfi_endproc.LFE35: .size sumstore, .-sumstore

- 46. What it really looks like .globl sumstore .type sumstore, @functionsumstore:.LFB35: .cfi_startproc pushq %rbx .cfi_def_cfa_offset 16 .cfi_offset

- 47. Assembly Characteristics: Data Types“Integer” data of 1,

- 48. Assembly Characteristics: OperationsTransfer data between memory and

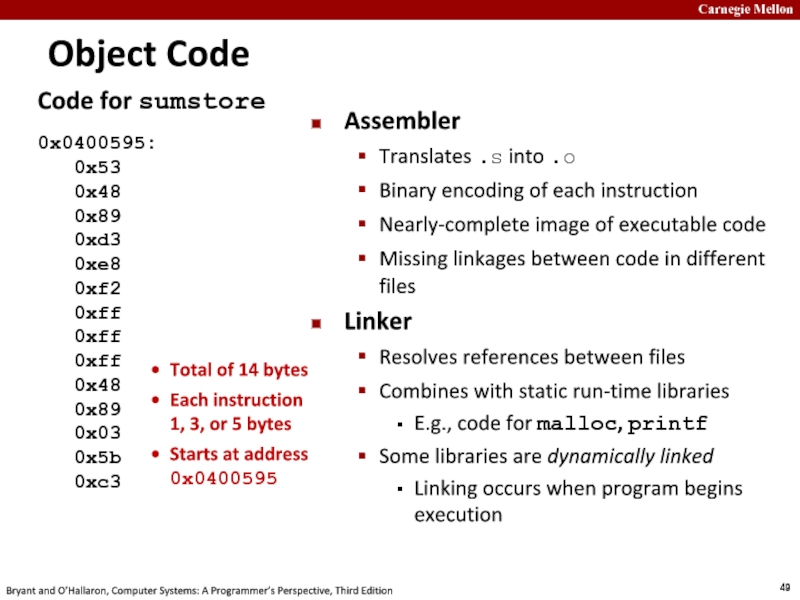

- 49. Code for sumstore0x0400595: 0x53 0x48

- 50. Machine Instruction ExampleC CodeStore value t where

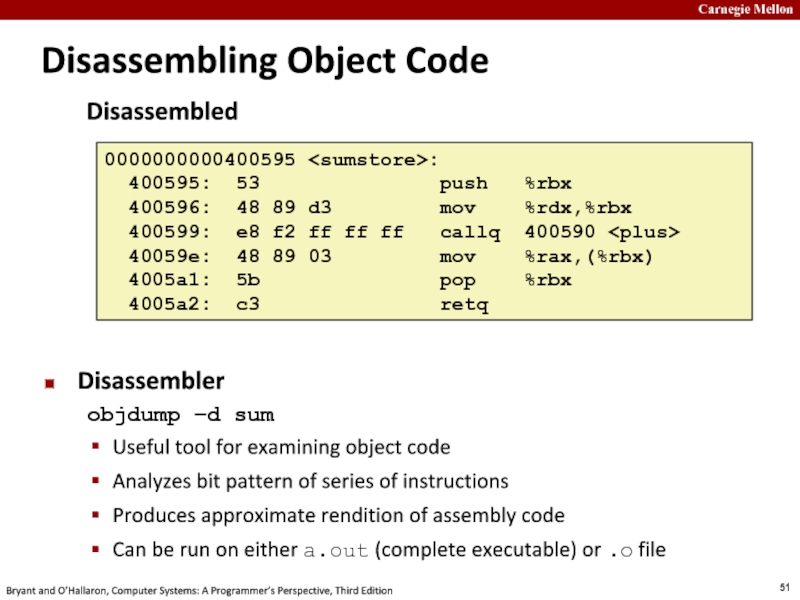

- 51. DisassembledDisassembling Object CodeDisassemblerobjdump –d sumUseful tool for

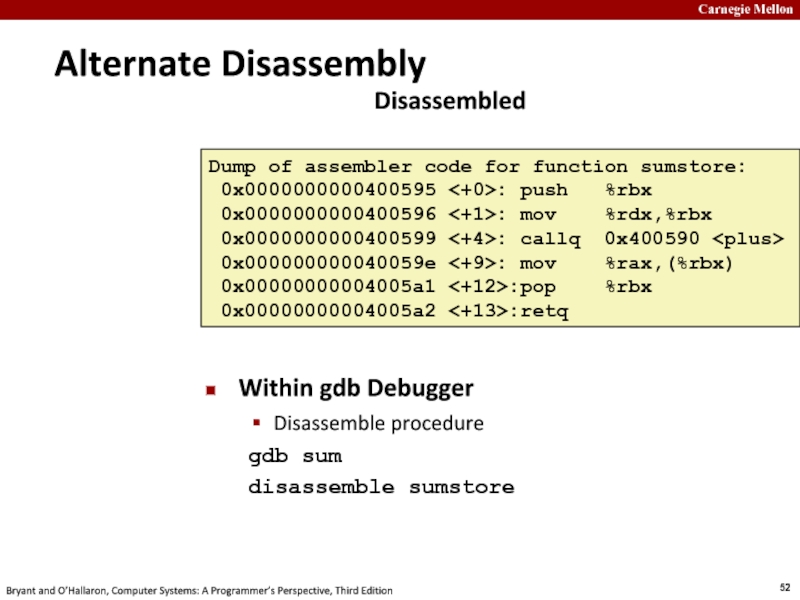

- 52. Alternate DisassemblyWithin gdb DebuggerDisassemble proceduregdb sumdisassemble sumstore

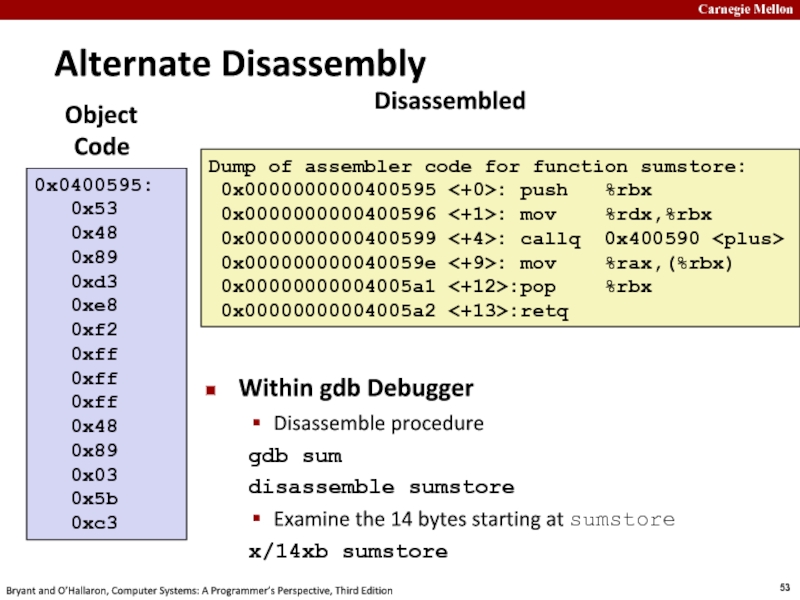

- 53. Alternate DisassemblyWithin gdb DebuggerDisassemble proceduregdb sumdisassemble sumstoreExamine the 14 bytes starting at sumstorex/14xb sumstore

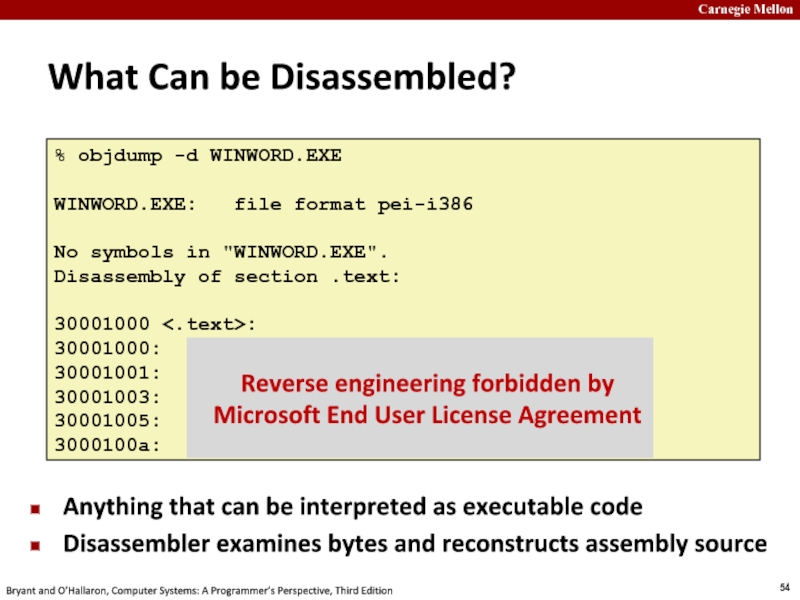

- 54. What Can be Disassembled?Anything that can be

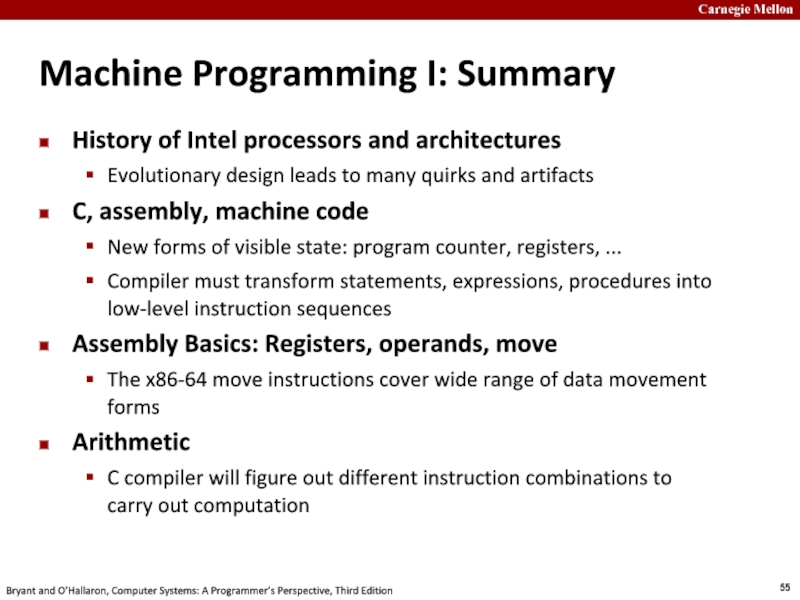

- 55. Machine Programming I: SummaryHistory of Intel processors

- 56. Скачать презентанцию

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 1Machine-Level Programming I: Basics 15-213/18-213: Introduction to Computer Systems 5th Lecture,

January 30, 2018

Слайд 2Office Hours

Not too well attended (yet?)

Ask your TAs about how

it was last

year…

You can choose from coffee, tea,

and

hot chocolateHere’s where my office is: HH A312

The time: Tues. 4pm-5pm

https://users.ece.cmu.edu/~franzf/officelocation.htm

Слайд 3Today: Machine Programming I: Basics

History of Intel processors and architectures

Assembly

Basics: Registers, operands, move

Arithmetic & logical operations

C, assembly, machine code

Слайд 4Intel x86 Processors

Dominate laptop/desktop/server market

Evolutionary design

Backwards compatible up until 8086,

introduced in 1978

Added more features as time goes on

Now 3

volumes, about 5,000 pages of documentationComplex instruction set computer (CISC)

Many different instructions with many different formats

But, only small subset encountered with Linux programs

Hard to match performance of Reduced Instruction Set Computers (RISC)

But, Intel has done just that!

In terms of speed. Less so for low power.

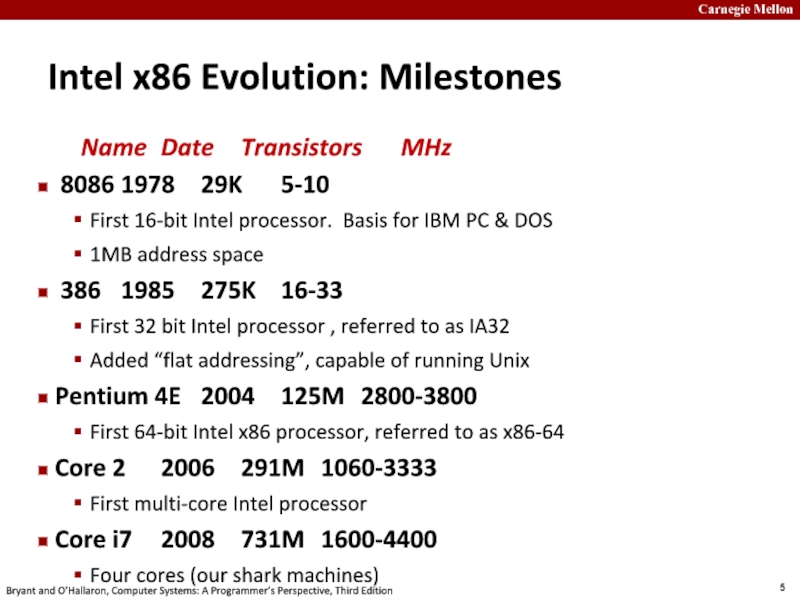

Слайд 5Intel x86 Evolution: Milestones

Name Date Transistors MHz

8086 1978 29K 5-10

First 16-bit Intel processor. Basis for IBM

PC & DOS

1MB address space

386 1985 275K 16-33

First 32 bit Intel processor ,

referred to as IA32Added “flat addressing”, capable of running Unix

Pentium 4E 2004 125M 2800-3800

First 64-bit Intel x86 processor, referred to as x86-64

Core 2 2006 291M 1060-3333

First multi-core Intel processor

Core i7 2008 731M 1600-4400

Four cores (our shark machines)

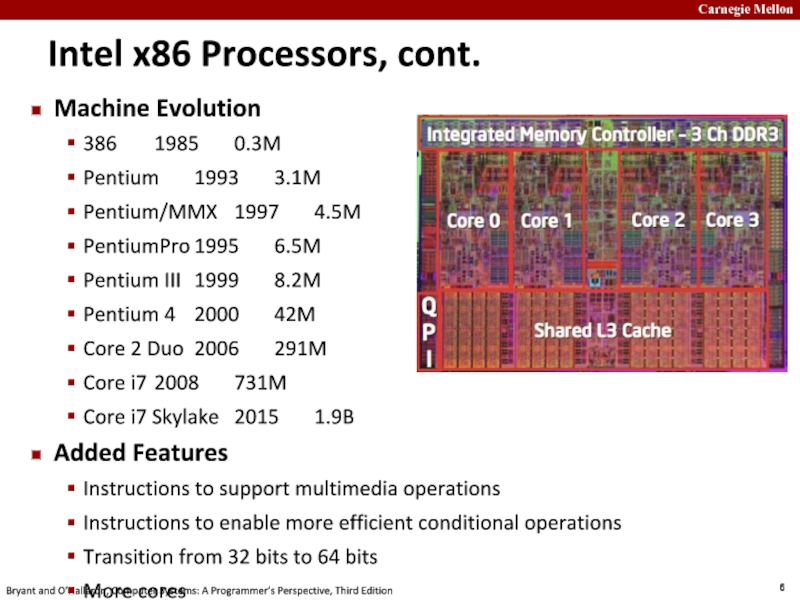

Слайд 6Intel x86 Processors, cont.

Machine Evolution

386 1985 0.3M

Pentium 1993 3.1M

Pentium/MMX 1997 4.5M

PentiumPro 1995 6.5M

Pentium III 1999 8.2M

Pentium 4 2000 42M

Core 2 Duo 2006 291M

Core i7 2008 731M

Core

i7 Skylake 2015 1.9B

Added Features

Instructions to support multimedia operations

Instructions to enable more

efficient conditional operationsTransition from 32 bits to 64 bits

More cores

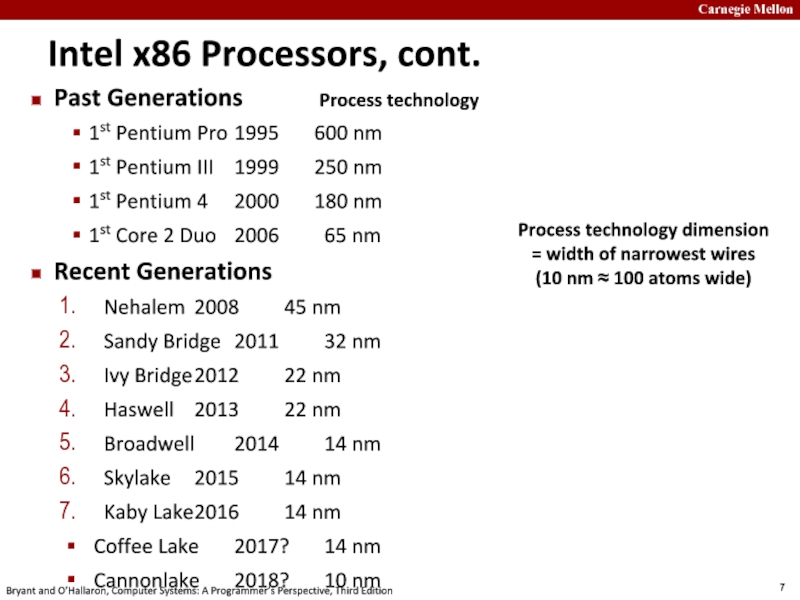

Слайд 7Intel x86 Processors, cont.

Past Generations

1st Pentium Pro 1995 600 nm

1st Pentium III 1999 250

nm

1st Pentium 4 2000 180 nm

1st Core 2 Duo 2006 65 nm

Recent Generations

Nehalem 2008

45 nm Sandy Bridge 2011 32 nm

Ivy Bridge 2012 22 nm

Haswell 2013 22 nm

Broadwell 2014 14 nm

Skylake 2015 14 nm

Kaby Lake 2016 14 nm

Coffee Lake 2017? 14 nm

Cannonlake 2018? 10 nm

Process technology

Process technology dimension

= width of narrowest wires

(10 nm ≈ 100 atoms wide)

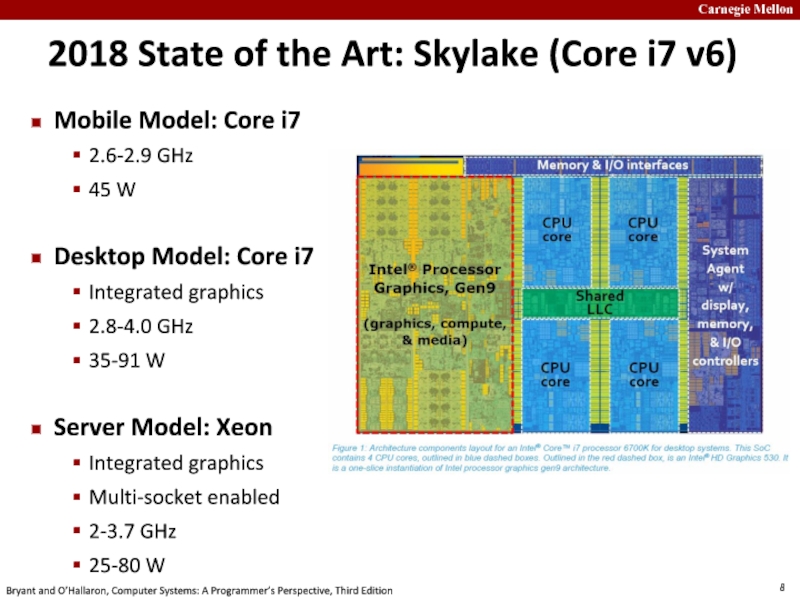

Слайд 82018 State of the Art: Skylake (Core i7 v6)

Mobile Model:

Core i7

2.6-2.9 GHz

45 W

Desktop Model: Core i7

Integrated graphics

2.8-4.0 GHz

35-91 W

Server

Model: XeonIntegrated graphics

Multi-socket enabled

2-3.7 GHz

25-80 W

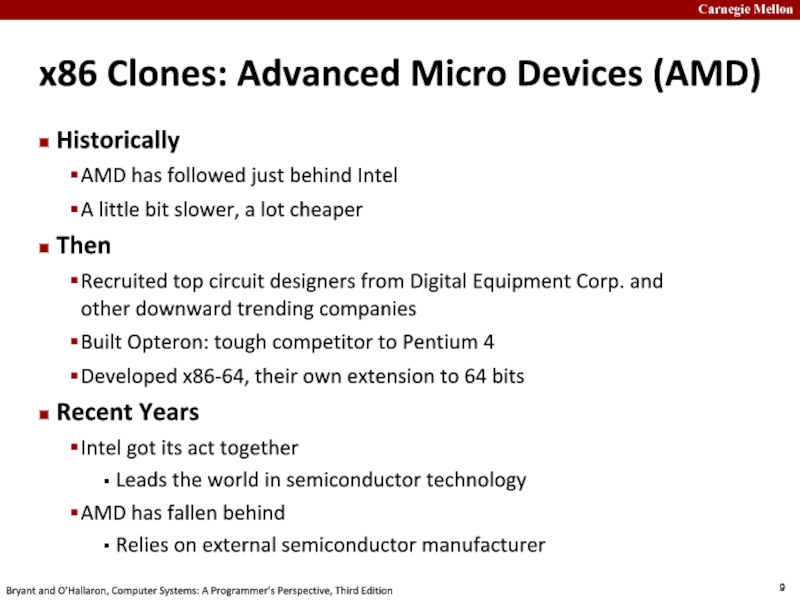

Слайд 9x86 Clones: Advanced Micro Devices (AMD)

Historically

AMD has followed just behind

Intel

A little bit slower, a lot cheaper

Then

Recruited top circuit designers

from Digital Equipment Corp. and other downward trending companiesBuilt Opteron: tough competitor to Pentium 4

Developed x86-64, their own extension to 64 bits

Recent Years

Intel got its act together

Leads the world in semiconductor technology

AMD has fallen behind

Relies on external semiconductor manufacturer

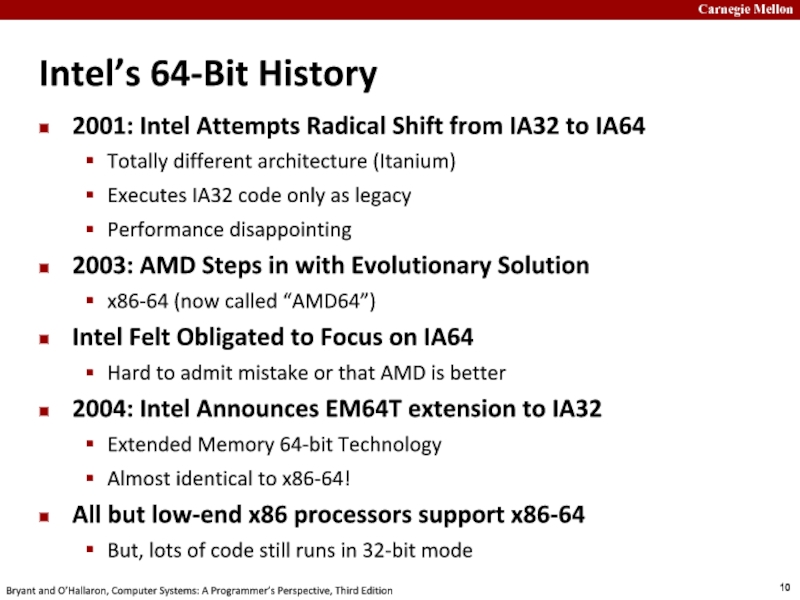

Слайд 10Intel’s 64-Bit History

2001: Intel Attempts Radical Shift from IA32 to

IA64

Totally different architecture (Itanium)

Executes IA32 code only as legacy

Performance disappointing

2003:

AMD Steps in with Evolutionary Solutionx86-64 (now called “AMD64”)

Intel Felt Obligated to Focus on IA64

Hard to admit mistake or that AMD is better

2004: Intel Announces EM64T extension to IA32

Extended Memory 64-bit Technology

Almost identical to x86-64!

All but low-end x86 processors support x86-64

But, lots of code still runs in 32-bit mode

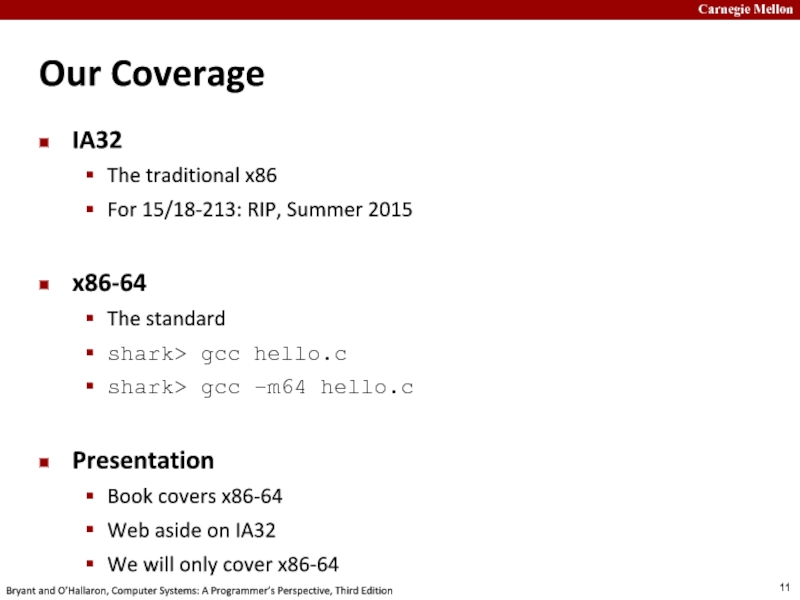

Слайд 11Our Coverage

IA32

The traditional x86

For 15/18-213: RIP, Summer 2015

x86-64

The standard

shark> gcc

hello.c

shark> gcc –m64 hello.c

Presentation

Book covers x86-64

Web aside on IA32

We will

only cover x86-64Слайд 12Today: Machine Programming I: Basics

History of Intel processors and architectures

Assembly

Basics: Registers, operands, move

Arithmetic & logical operations

C, assembly, machine code

Слайд 13Levels of Abstraction

C programmer

Assembly programmer

Computer Designer

C code

Caches, clock freq, layout,

…

Nice clean layers,

but beware…

Of course, you know that:

It’s why you are taking this course.Слайд 14Definitions

Architecture: (also ISA: instruction set architecture) The parts of a

processor design that one needs to understand for writing assembly/machine

code.Examples: instruction set specification, registers

Microarchitecture: Implementation of the architecture

Examples: cache sizes and core frequency

Code Forms:

Machine Code: The byte-level programs that a processor executes

Assembly Code: A text representation of machine code

Example ISAs:

Intel: x86, IA32, Itanium, x86-64

ARM: Used in almost all mobile phones

RISC V: New open-source ISA

Слайд 15CPU

Assembly/Machine Code View

Programmer-Visible State

PC: Program counter

Address of next instruction

Called “RIP”

(x86-64)

Register file

Heavily used program data

Condition codes

Store status information about most

recent arithmetic or logical operationUsed for conditional branching

PC

Registers

Memory

Code

Data

Stack

Addresses

Data

Instructions

Condition

Codes

Memory

Byte addressable array

Code and user data

Stack to support procedures

Слайд 16Assembly Characteristics: Data Types

“Integer” data of 1, 2, 4, or

8 bytes

Data values

Addresses (untyped pointers)

Floating point data of 4, 8,

or 10 bytes(SIMD vector data types of 8, 16, 32 or 64 bytes)

Code: Byte sequences encoding series of instructions

No aggregate types such as arrays or structures

Just contiguously allocated bytes in memory

Слайд 17%rsp

x86-64 Integer Registers

Can reference low-order 4 bytes (also low-order 1

& 2 bytes)

Not part of memory (or cache)

%eax

%ebx

%ecx

%edx

%esi

%edi

%esp

%ebp

%r8d

%r9d

%r10d

%r11d

%r12d

%r13d

%r14d

%r15d

%r8

%r9

%r10

%r11

%r12

%r13

%r14

%r15

%rax

%rbx

%rcx

%rdx

%rsi

%rdi

%rbp

Слайд 18Some History: IA32 Registers

%ax

%cx

%dx

%bx

%si

%di

%sp

%bp

%ah

%ch

%dh

%bh

%al

%cl

%dl

%bl

16-bit virtual registers

(backwards compatibility)

general purpose

accumulate

counter

data

base

source

index

destination

index

stack

pointer

base

pointer

Origin

(mostly

obsolete)

Слайд 19Assembly Characteristics: Operations

Transfer data between memory and register

Load data from

memory into register

Store register data into memory

Perform arithmetic function on

register or memory dataTransfer control

Unconditional jumps to/from procedures

Conditional branches

Indirect branches

Слайд 20Moving Data

Moving Data

movq Source, Dest

Operand Types

Immediate: Constant integer data

Example: $0x400,

$-533

Like C constant, but prefixed with ‘$’

Encoded with 1, 2,

or 4 bytesRegister: One of 16 integer registers

Example: %rax, %r13

But %rsp reserved for special use

Others have special uses for particular instructions

Memory: 8 consecutive bytes of memory at address given by register

Simplest example: (%rax)

Various other “addressing modes”

Warning: Intel docs use

mov Dest, Source

Слайд 21movq Operand Combinations

Cannot do memory-memory transfer with a single instruction

movq

Imm

Reg

Mem

Reg

Mem

Reg

Mem

Reg

Source

Dest

C

Analog

movq $0x4,%rax

temp = 0x4;

movq $-147,(%rax)

*p = -147;

movq %rax,%rdx

temp2 = temp1;

movq

%rax,(%rdx)*p = temp;

movq (%rax),%rdx

temp = *p;

Src,Dest

Слайд 22Simple Memory Addressing Modes

Normal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]

Register R specifies memory address

Aha! Pointer dereferencing

in C

movq (%rcx),%rax

Displacement D(R) Mem[Reg[R]+D]

Register R specifies start of memory region

Constant displacement

D specifies offset

movq 8(%rbp),%rdxСлайд 23Example of Simple Addressing Modes

whatAmI:

movq (%rdi), %rax

movq (%rsi), %rdx

movq %rdx, (%rdi)

movq %rax, (%rsi)ret

void

whatAmI(

{

????

}

Слайд 24Example of Simple Addressing Modes

void swap

(long *xp, long

*yp)

{

long t0 = *xp;

long t1 = *yp;

*xp = t1;*yp = t0;

}

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax

movq (%rsi), %rdx

movq %rdx, (%rdi)

movq %rax, (%rsi)

ret

Слайд 25Understanding Swap()

void swap

(long *xp, long *yp)

{

long

t0 = *xp;

long t1 = *yp;

*xp = t1;

*yp = t0;}

Memory

Register Value

%rdi xp

%rsi yp

%rax t0

%rdx t1

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax # t0 = *xp

movq (%rsi), %rdx # t1 = *yp

movq %rdx, (%rdi) # *xp = t1

movq %rax, (%rsi) # *yp = t0

ret

Registers

Слайд 26Understanding Swap()

123

456

Registers

Memory

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax # t0 =

*xp

movq (%rsi), %rdx # t1 =

*ypmovq %rdx, (%rdi) # *xp = t1

movq %rax, (%rsi) # *yp = t0

ret

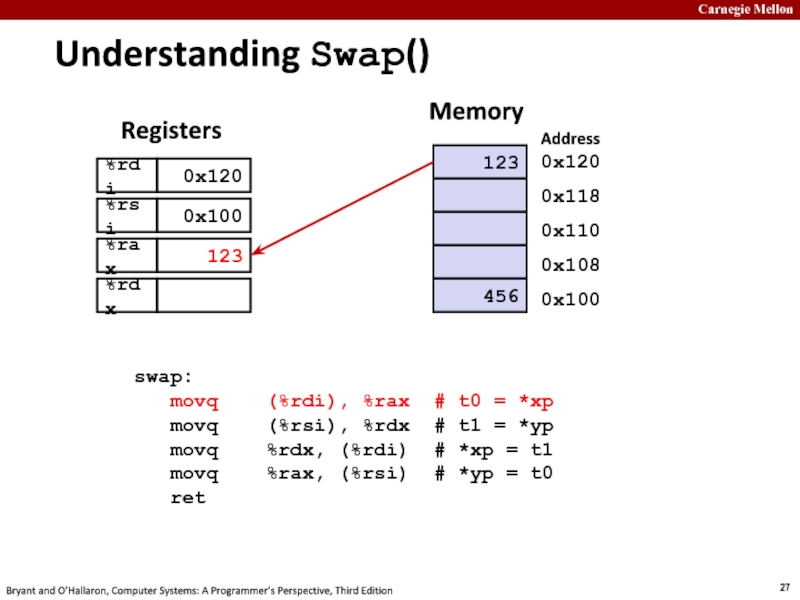

Слайд 27Understanding Swap()

123

456

Registers

Memory

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax # t0 =

*xp

movq (%rsi), %rdx # t1 =

*ypmovq %rdx, (%rdi) # *xp = t1

movq %rax, (%rsi) # *yp = t0

ret

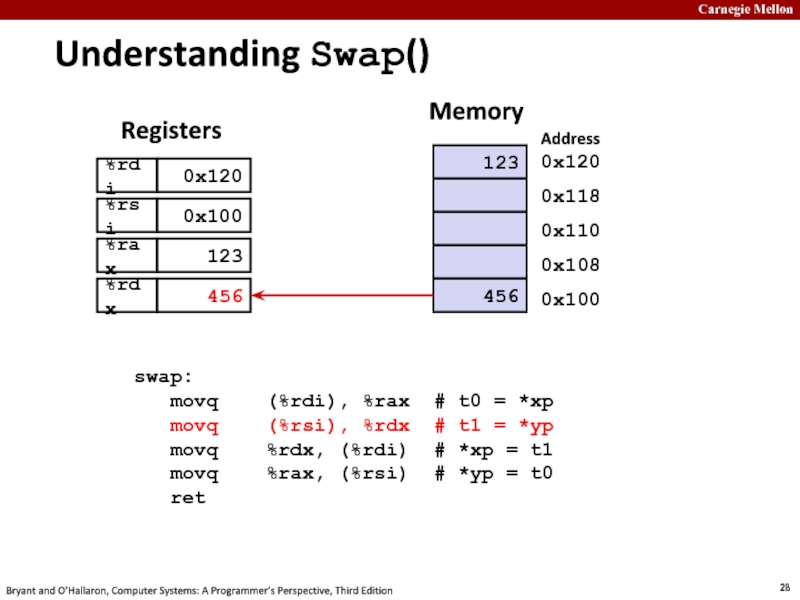

Слайд 28Understanding Swap()

123

456

Registers

Memory

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax # t0 =

*xp

movq (%rsi), %rdx # t1 =

*ypmovq %rdx, (%rdi) # *xp = t1

movq %rax, (%rsi) # *yp = t0

ret

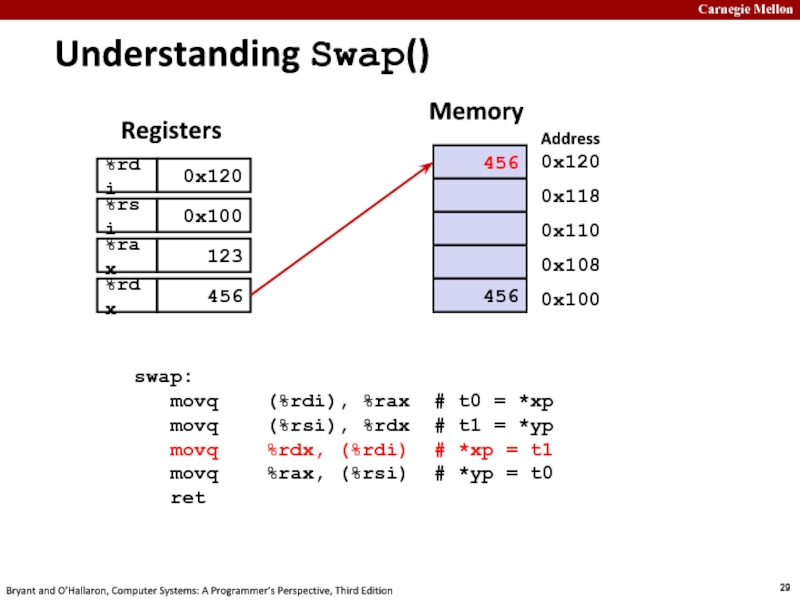

Слайд 29Understanding Swap()

456

456

Registers

Memory

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax # t0 =

*xp

movq (%rsi), %rdx # t1 =

*ypmovq %rdx, (%rdi) # *xp = t1

movq %rax, (%rsi) # *yp = t0

ret

Слайд 30Understanding Swap()

456

123

Registers

Memory

swap:

movq (%rdi), %rax # t0 =

*xp

movq (%rsi), %rdx # t1 =

*ypmovq %rdx, (%rdi) # *xp = t1

movq %rax, (%rsi) # *yp = t0

ret

Слайд 31Simple Memory Addressing Modes

Normal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]

Register R specifies memory address

Aha! Pointer dereferencing

in C

movq (%rcx),%rax

Displacement D(R) Mem[Reg[R]+D]

Register R specifies start of memory region

Constant displacement

D specifies offset

movq 8(%rbp),%rdxСлайд 32Complete Memory Addressing Modes

Most General Form

D(Rb,Ri,S) Mem[Reg[Rb]+S*Reg[Ri]+ D]

D: Constant “displacement” 1,

2, or 4 bytes

Rb: Base register: Any of 16 integer

registersRi: Index register: Any, except for %rsp

S: Scale: 1, 2, 4, or 8 (why these numbers?)

Special Cases

(Rb,Ri) Mem[Reg[Rb]+Reg[Ri]]

D(Rb,Ri) Mem[Reg[Rb]+Reg[Ri]+D]

(Rb,Ri,S) Mem[Reg[Rb]+S*Reg[Ri]]

Слайд 35Today: Machine Programming I: Basics

History of Intel processors and architectures

Assembly

Basics: Registers, operands, move

Arithmetic & logical operations

C, assembly, machine code

Слайд 36Address Computation Instruction

leaq Src, Dst

Src is address mode expression

Set Dst

to address denoted by expression

Uses

Computing addresses without a memory reference

E.g.,

translation of p = &x[i];Computing arithmetic expressions of the form x + k*y

k = 1, 2, 4, or 8

Example

long m12(long x)

{

return x*12;

}

leaq (%rdi,%rdi,2), %rax # t = x+2*x

salq $2, %rax # return t<<2

Converted to ASM by compiler:

Слайд 37Some Arithmetic Operations

Two Operand Instructions:

Format Computation

addq Src,Dest Dest = Dest + Src

subq Src,Dest Dest =

Dest Src

imulq Src,Dest Dest = Dest * Src

salq Src,Dest Dest = Dest

Src Also called shlqsarq Src,Dest Dest = Dest >> Src Arithmetic

shrq Src,Dest Dest = Dest >> Src Logical

xorq Src,Dest Dest = Dest ^ Src

andq Src,Dest Dest = Dest & Src

orq Src,Dest Dest = Dest | Src

Watch out for argument order! Src,Dest (Warning: Intel docs use “op Dest,Src”)

No distinction between signed and unsigned int (why?)

Слайд 38Quiz Time! halblustig: German, literal translation: “semi-funny” but often means “not funny

at all” in Austrian German

Check out: quiz: day 5: Machine

Basicshttps://canvas.cmu.edu/courses/3822

Слайд 39Some Arithmetic Operations

One Operand Instructions

incq Dest Dest = Dest + 1

decq Dest Dest =

Dest 1

negq Dest Dest = Dest

notq Dest Dest = ~Dest

See book for

more instructionsСлайд 40Arithmetic Expression Example

Interesting Instructions

leaq: address computation

salq: shift

imulq: multiplication

But, only used

once

long arith

(long x, long y, long z)

{

long t1 =

x+y;long t2 = z+t1;

long t3 = x+4;

long t4 = y * 48;

long t5 = t3 + t4;

long rval = t2 * t5;

return rval;

}

arith:

leaq (%rdi,%rsi), %rax

addq %rdx, %rax

leaq (%rsi,%rsi,2), %rdx

salq $4, %rdx

leaq 4(%rdi,%rdx), %rcx

imulq %rcx, %rax

ret

Слайд 41Understanding Arithmetic Expression Example

long arith

(long x, long y, long z)

{

long t1 = x+y;

long t2 = z+t1;

long t3

= x+4;long t4 = y * 48;

long t5 = t3 + t4;

long rval = t2 * t5;

return rval;

}

arith:

leaq (%rdi,%rsi), %rax # t1

addq %rdx, %rax # t2

leaq (%rsi,%rsi,2), %rdx

salq $4, %rdx # t4

leaq 4(%rdi,%rdx), %rcx # t5

imulq %rcx, %rax # rval

ret

Compiler optimization:

Reuse of registers

Substitution (copy propagation)

Strength reduction

Слайд 42Today: Machine Programming I: Basics

History of Intel processors and architectures

Assembly

Basics: Registers, operands, move

Arithmetic & logical operations

C, assembly, machine code

Слайд 43text

text

binary

binary

Compiler (gcc –Og -S)

Assembler (gcc or as)

Linker (gcc or ld)

C

program (p1.c p2.c)

Asm program (p1.s p2.s)

Object program (p1.o p2.o)

Executable program

(p)Static libraries (.a)

Turning C into Object Code

Code in files p1.c p2.c

Compile with command: gcc –Og p1.c p2.c -o p

Use basic optimizations (-Og) [New to recent versions of GCC]

Put resulting binary in file p

Слайд 44Compiling Into Assembly

C Code (sum.c)

long plus(long x, long y);

void

sumstore(long x, long y,

long *dest){

long t = plus(x, y);

*dest = t;

}

Generated x86-64 Assembly

sumstore:

pushq %rbx

movq %rdx, %rbx

call plus

movq %rax, (%rbx)

popq %rbx

ret

Obtain (on shark machine) with command

gcc –Og –S sum.c

Produces file sum.s

Warning: Will get very different results on non-Shark machines (Andrew Linux, Mac OS-X, …) due to different versions of gcc and different compiler settings.

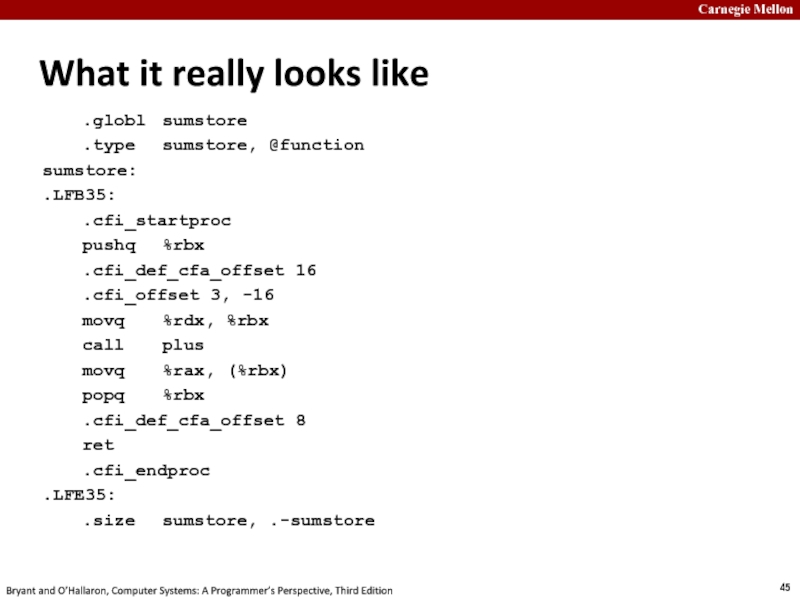

Слайд 45What it really looks like

.globl sumstore

.type sumstore, @function

sumstore:

.LFB35:

.cfi_startproc

pushq %rbx

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 16

.cfi_offset 3, -16

movq %rdx, %rbx

call plus

movq %rax,

(%rbx)

popq %rbx

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 8

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE35:

.size sumstore, .-sumstore

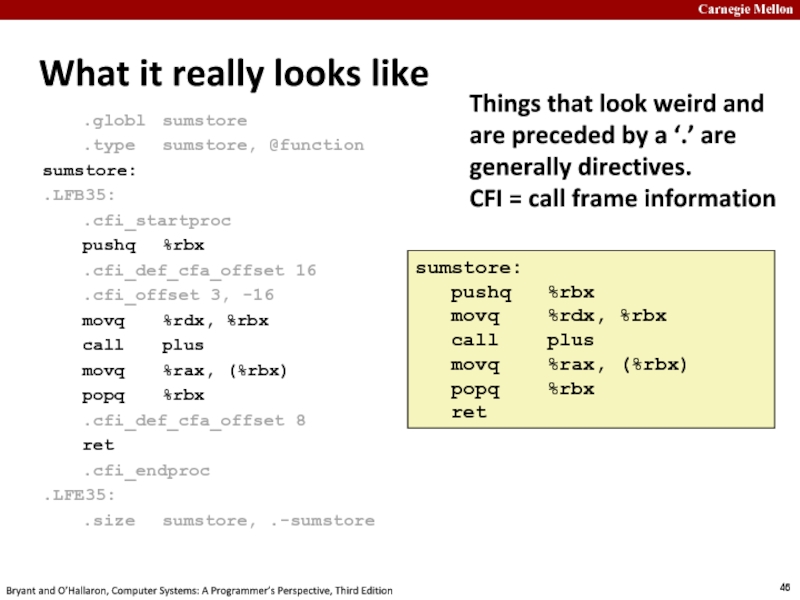

Слайд 46What it really looks like

.globl sumstore

.type sumstore, @function

sumstore:

.LFB35:

.cfi_startproc

pushq %rbx

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 16

.cfi_offset 3, -16

movq %rdx, %rbx

call plus

movq %rax,

(%rbx)

popq %rbx

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 8

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE35:

.size sumstore, .-sumstore

Things that look weird and are preceded by

a ‘.’ are generally directives. CFI = call frame information

sumstore:

pushq %rbx

movq %rdx, %rbx

call plus

movq %rax, (%rbx)

popq %rbx

ret

Слайд 47Assembly Characteristics: Data Types

“Integer” data of 1, 2, 4, or

8 bytes

Data values

Addresses (untyped pointers)

Floating point data of 4, 8,

or 10 bytes(SIMD vector data types of 8, 16, 32 or 64 bytes)

Code: Byte sequences encoding series of instructions

No aggregate types such as arrays or structures

Just contiguously allocated bytes in memory

Слайд 48Assembly Characteristics: Operations

Transfer data between memory and register

Load data from

memory into register

Store register data into memory

Perform arithmetic function on

register or memory dataTransfer control

Unconditional jumps to/from procedures

Conditional branches

Indirect branch

Слайд 49Code for sumstore

0x0400595:

0x53

0x48

0x89

0xd3

0xe8

0xf2

0xff

0xff

0xff0x48

0x89

0x03

0x5b

0xc3

Object Code

Assembler

Translates .s into .o

Binary encoding of each instruction

Nearly-complete image of executable code

Missing linkages between code in different files

Linker

Resolves references between files

Combines with static run-time libraries

E.g., code for malloc, printf

Some libraries are dynamically linked

Linking occurs when program begins execution

Total of 14 bytes

Each instruction 1, 3, or 5 bytes

Starts at address 0x0400595

Слайд 50Machine Instruction Example

C Code

Store value t where designated by dest

Assembly

Move

8-byte value to memory

Quad words in x86-64 parlance

Operands:

t: Register %rax

dest: Register %rbx

*dest: Memory M[%rbx]

Object Code

3-byte

instructionStored at address 0x40059e

*dest = t;

movq %rax, (%rbx)

0x40059e: 48 89 03

Слайд 51Disassembled

Disassembling Object Code

Disassembler

objdump –d sum

Useful tool for examining object code

Analyzes

bit pattern of series of instructions

Produces approximate rendition of assembly

codeCan be run on either a.out (complete executable) or .o file

0000000000400595

400595: 53 push %rbx

400596: 48 89 d3 mov %rdx,%rbx

400599: e8 f2 ff ff ff callq 400590

40059e: 48 89 03 mov %rax,(%rbx)

4005a1: 5b pop %rbx

4005a2: c3 retq

Слайд 53Alternate Disassembly

Within gdb Debugger

Disassemble procedure

gdb sum

disassemble sumstore

Examine the 14 bytes

starting at sumstore

x/14xb sumstore

Слайд 54What Can be Disassembled?

Anything that can be interpreted as executable

code

Disassembler examines bytes and reconstructs assembly source

% objdump -d WINWORD.EXE

WINWORD.EXE:

file format pei-i386No symbols in "WINWORD.EXE".

Disassembly of section .text:

30001000 <.text>:

30001000: 55 push %ebp

30001001: 8b ec mov %esp,%ebp

30001003: 6a ff push $0xffffffff

30001005: 68 90 10 00 30 push $0x30001090

3000100a: 68 91 dc 4c 30 push $0x304cdc91

Reverse engineering forbidden by

Microsoft End User License Agreement

Слайд 55Machine Programming I: Summary

History of Intel processors and architectures

Evolutionary design

leads to many quirks and artifacts

C, assembly, machine code

New forms

of visible state: program counter, registers, ...Compiler must transform statements, expressions, procedures into low-level instruction sequences

Assembly Basics: Registers, operands, move

The x86-64 move instructions cover wide range of data movement forms

Arithmetic

C compiler will figure out different instruction combinations to carry out computation

![Machine-Level Programming I: Basics 15-213/18-213 : Introduction to Computer Simple Memory Addressing ModesNormal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]Register R specifies memory addressAha! Pointer dereferencing in Simple Memory Addressing ModesNormal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]Register R specifies memory addressAha! Pointer dereferencing in C movq (%rcx),%raxDisplacement D(R) Mem[Reg[R]+D]Register R specifies](/img/thumbs/63f1ce6c78df4613e7688ae59e1b4fbe-800x.jpg)

![Machine-Level Programming I: Basics 15-213/18-213 : Introduction to Computer Simple Memory Addressing ModesNormal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]Register R specifies memory addressAha! Pointer dereferencing in Simple Memory Addressing ModesNormal (R) Mem[Reg[R]]Register R specifies memory addressAha! Pointer dereferencing in C movq (%rcx),%raxDisplacement D(R) Mem[Reg[R]+D]Register R specifies](/img/tmb/3/283077/e2e4cd4a19c8b20217e090f5b931ffed-800x.jpg)

![Machine-Level Programming I: Basics 15-213/18-213 : Introduction to Computer Complete Memory Addressing ModesMost General Form D(Rb,Ri,S) Mem[Reg[Rb]+S*Reg[Ri]+ D]D: Constant “displacement” 1, 2, Complete Memory Addressing ModesMost General Form D(Rb,Ri,S) Mem[Reg[Rb]+S*Reg[Ri]+ D]D: Constant “displacement” 1, 2, or 4 bytesRb: Base register: Any](/img/tmb/3/283077/af7fb74a9f35d5ca21c46d649c854fd0-800x.jpg)