Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Sculpture

Содержание

- 1. Sculpture

- 2. Sculpture Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that

- 3. SculptureSculpture in stone survives far better than

- 4. TypesA basic distinction is between sculpture in

- 5. statuesstatues

- 6. Purposes and subjects One of the most

- 7. Purposes and subjects Purposes and subjects

- 8. Metal Bronze and related copper alloys are the oldest and

- 9. Metal Bronze

- 10. Lost-wax casting A model of an apple

- 11. Lost-wax castingA model of an apple in wax

- 12. Gold Gold is a chemical element with symbol Au (from Latin: aurum) and atomic number 79,

- 13. GoldGold

- 14. Wood carving Wood carving is a form of woodworking by

- 15. Wood carving Wood carving

- 16. Prehistoric periods The earliest undisputed examples of

- 17. Prehistoric periods Prehistoric periods

- 18. Ancient Egypt The monumental sculpture of ancient Egypt is

- 19. Ancient Egypt Ancient Egypt

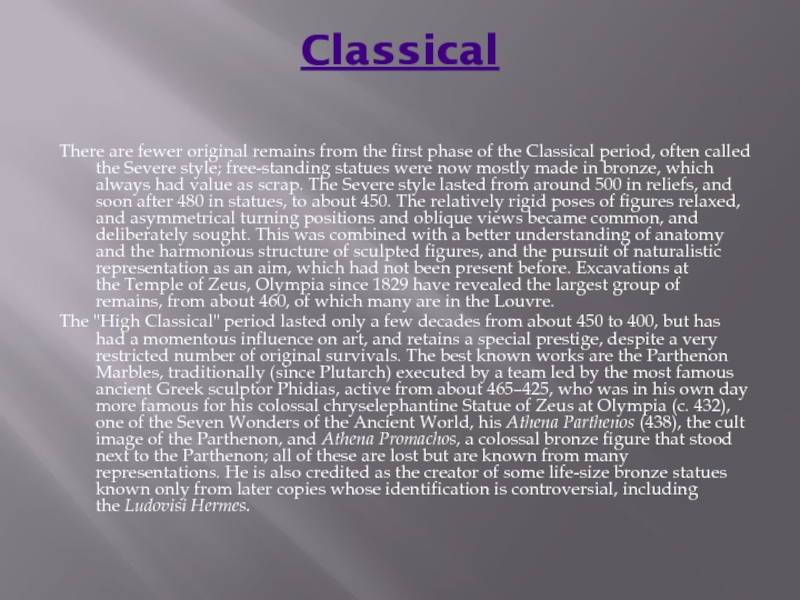

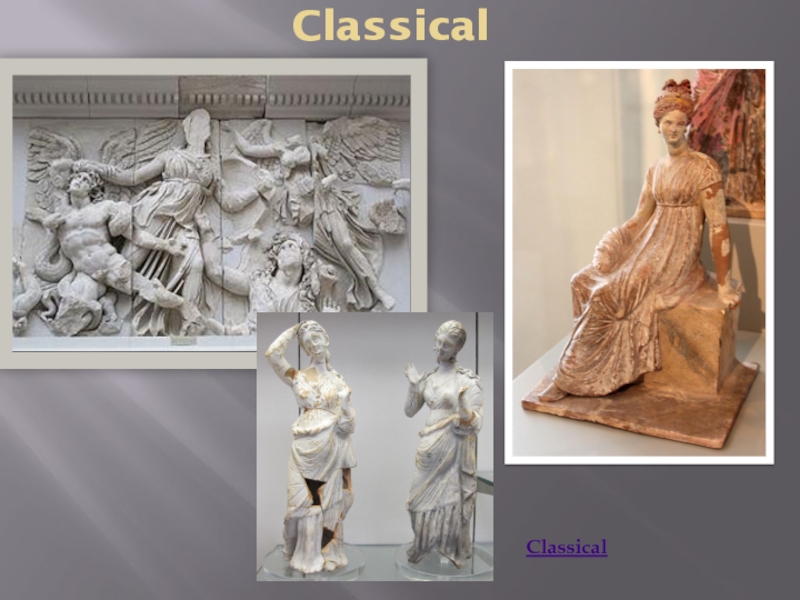

- 20. Classical There are fewer original remains from

- 21. Classical Classical

- 22. Слайд 22

- 23. Скачать презентанцию

Sculpture Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sculptural processes originally used carving (the removal of material) and modelling (the addition of material, as

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 3Sculpture

Sculpture in stone survives far better than works of art

in perishable materials, and often represents the majority of the

surviving works (other than pottery) from ancient cultures, though conversely traditions of sculpture in wood may have vanished almost entirely. However, most ancient sculpture was brightly painted, and this has been lost.Sculpture has been central in religious devotion in many cultures, and until recent centuries large sculptures, too expensive for private individuals to create, were usually an expression of religion or politics. Those cultures whose sculptures have survived in quantities include the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, India and China, as well as many in Central and South America and Africa.

The Western tradition of sculpture began in ancient Greece, and Greece is widely seen as producing great masterpieces in the classical period. During the Middle Ages, Gothic sculpture represented the agonies and passions of the Christian faith. The revival of classical models in the Renaissance produced famous sculptures such as Michelangelo's David. Modernist sculpture moved away from traditional processes and the emphasis on the depiction of the human body, with the making of constructed sculpture, and the presentation of found objects as finished art works.

Слайд 4Types

A basic distinction is between sculpture in the round, free-standing

sculpture, such as statues, not attached (except possibly at the base)

to any other surface, and the various types of relief, which are at least partly attached to a background surface. Relief is often classified by the degree of projection from the wall into low or bas-relief, high relief, and sometimes an intermediate mid-relief. Sunk-relief is a technique restricted to ancient Egypt. Relief is the usual sculptural medium for large figure groups and narrative subjects, which are difficult to accomplish in the round, and is the typical technique used both for architectural sculpture, which is attached to buildings, and for small-scale sculpture decorating other objects, as in much pottery, metalwork and jewellery. Relief sculpture may also decorate steles, upright slabs, usually of stone, often also containing inscriptions.Another basic distinction is between subtractive carving techniques, which remove material from an existing block or lump, for example of stone or wood, and modelling techniques which shape or build up the work from the material. Techniques such as casting, stamping and moulding use an intermediate matrix containing the design to produce the work; many of these allow the production of several copies.

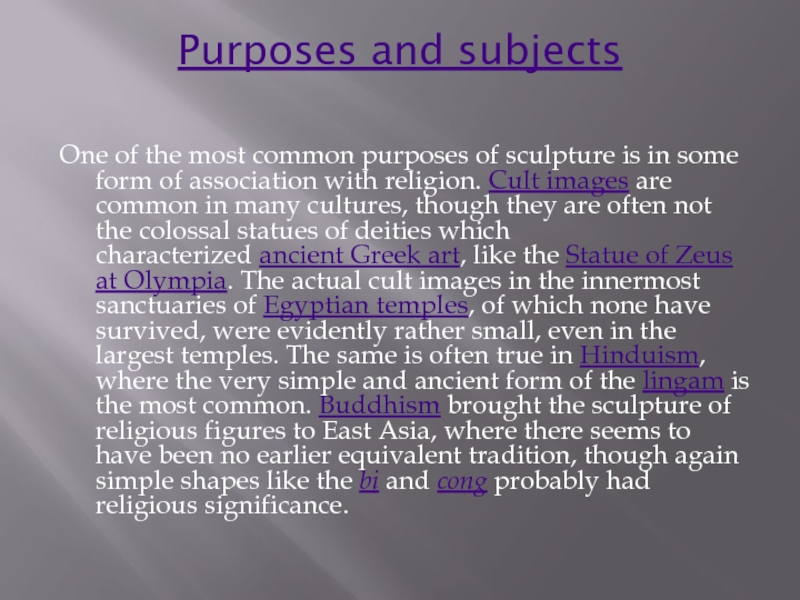

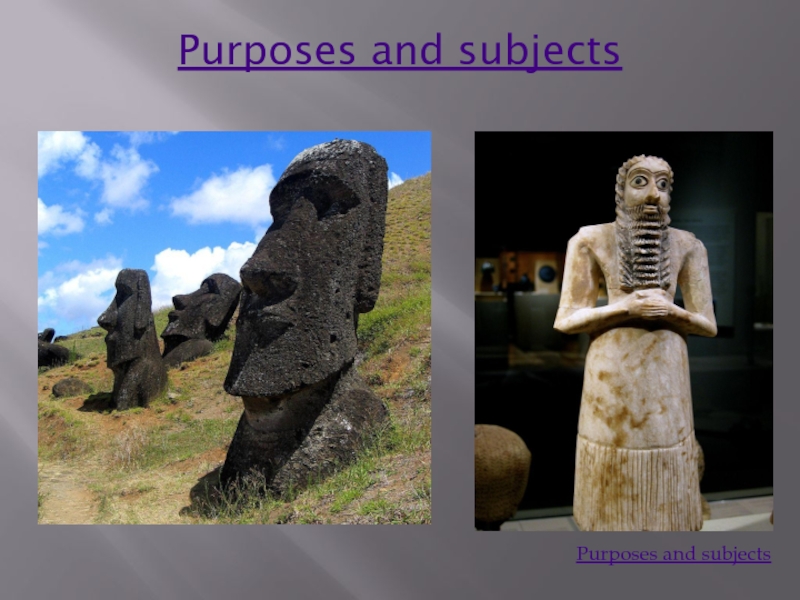

Слайд 6Purposes and subjects

One of the most common purposes of sculpture

is in some form of association with religion. Cult images are common

in many cultures, though they are often not the colossal statues of deities which characterized ancient Greek art, like the Statue of Zeus at Olympia. The actual cult images in the innermost sanctuaries of Egyptian temples, of which none have survived, were evidently rather small, even in the largest temples. The same is often true in Hinduism, where the very simple and ancient form of the lingam is the most common. Buddhism brought the sculpture of religious figures to East Asia, where there seems to have been no earlier equivalent tradition, though again simple shapes like the bi and cong probably had religious significance.Слайд 8Metal

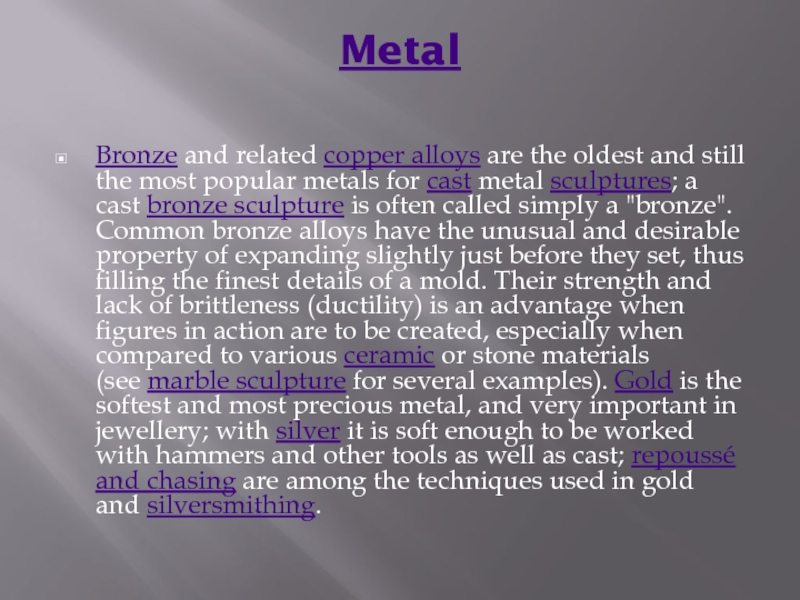

Bronze and related copper alloys are the oldest and still the most popular

metals for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply a "bronze".

Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mold. Their strength and lack of brittleness (ductility) is an advantage when figures in action are to be created, especially when compared to various ceramic or stone materials (see marble sculpture for several examples). Gold is the softest and most precious metal, and very important in jewellery; with silver it is soft enough to be worked with hammers and other tools as well as cast; repoussé and chasing are among the techniques used in gold and silversmithing.Слайд 10Lost-wax casting

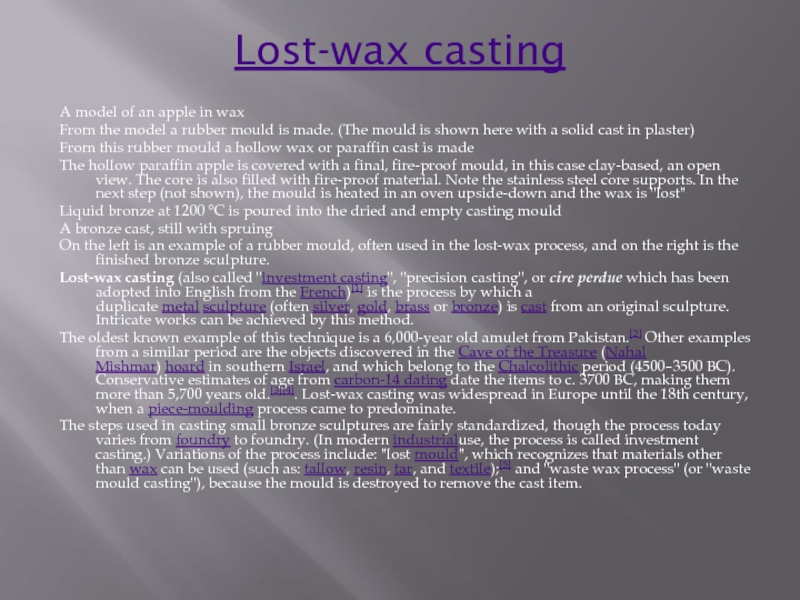

A model of an apple in wax

From the model

a rubber mould is made. (The mould is shown here

with a solid cast in plaster)From this rubber mould a hollow wax or paraffin cast is made

The hollow paraffin apple is covered with a final, fire-proof mould, in this case clay-based, an open view. The core is also filled with fire-proof material. Note the stainless steel core supports. In the next step (not shown), the mould is heated in an oven upside-down and the wax is "lost"

Liquid bronze at 1200 °C is poured into the dried and empty casting mould

A bronze cast, still with spruing

On the left is an example of a rubber mould, often used in the lost-wax process, and on the right is the finished bronze sculpture.

Lost-wax casting (also called "investment casting", "precision casting", or cire perdue which has been adopted into English from the French)[1] is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass or bronze) is cast from an original sculpture. Intricate works can be achieved by this method.

The oldest known example of this technique is a 6,000-year old amulet from Pakistan.[2] Other examples from a similar period are the objects discovered in the Cave of the Treasure (Nahal Mishmar) hoard in southern Israel, and which belong to the Chalcolithic period (4500–3500 BC). Conservative estimates of age from carbon-14 dating date the items to c. 3700 BC, making them more than 5,700 years old.[3][4]. Lost-wax casting was widespread in Europe until the 18th century, when a piece-moulding process came to predominate.

The steps used in casting small bronze sculptures are fairly standardized, though the process today varies from foundry to foundry. (In modern industrialuse, the process is called investment casting.) Variations of the process include: "lost mould", which recognizes that materials other than wax can be used (such as: tallow, resin, tar, and textile);[5] and "waste wax process" (or "waste mould casting"), because the mould is destroyed to remove the cast item.

Слайд 12Gold

Gold is a chemical element with symbol Au (from Latin: aurum) and atomic number 79, making it one of

the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. In its purest form,

it is a bright, slightly reddish yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal and a group 11 element. It is one of the least reactive chemical elements and is solid under standard conditions. Gold often occurs in free elemental (native) form, as nuggets or grains, in rocks, in veins, and in alluvial deposits. It occurs in a solid solution series with the native element silver (as electrum) and also naturally alloyed with copper and palladium. Less commonly, it occurs in minerals as gold compounds, often with tellurium (gold tellurides).Gold is resistant to most acids, though it does dissolve in aqua regia, a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, which forms a soluble tetrachloroaurate anion. Gold is insoluble in nitric acid, which dissolves silver and base metals, a property that has long been used to refinegold and to confirm the presence of gold in metallic objects, giving rise to the term acid test. Gold also dissolves in alkaline solutions of cyanide, which are used in mining and electroplating. Gold dissolves in mercury, forming amalgam alloys, but this is not a chemical reaction.

Слайд 14Wood carving

Wood carving is a form of woodworking by means of a cutting

tool (knife) in one hand or a chisel by two hands or

with one hand on a chisel and one hand on a mallet, resulting in a wooden figure or figurine, or in the sculptural ornamentation of a wooden object. The phrase may also refer to the finished product, from individual sculptures to hand-worked mouldings composing part of a tracery.The making of sculpture in wood has been extremely widely practiced, but survives much less well than the other main materials such as stone and bronze, as it is vulnerable to decay, insect damage, and fire. It therefore forms an important hidden element in the art history of many cultures.[1] Outdoor wood sculptures do not last long in most parts of the world, so it is still unknown how the totem pole tradition developed. Many of the most important sculptures of China and Japan in particular are in wood, and so are the great majority of African sculpture and that of Oceania and other regions. Wood is light and can take very fine detail so it is highly suitable for masks and other sculpture intended to be worn or carried. It is also much easier to work on than stone.

Some of the finest extant examples of early European wood carving are from the Middle Ages in Germany, Russia, Italy and France, where the typical themes of that era were Christian iconography. In England, many complete examples remain from the 16th and 17th century, where oak was the preferred medium.

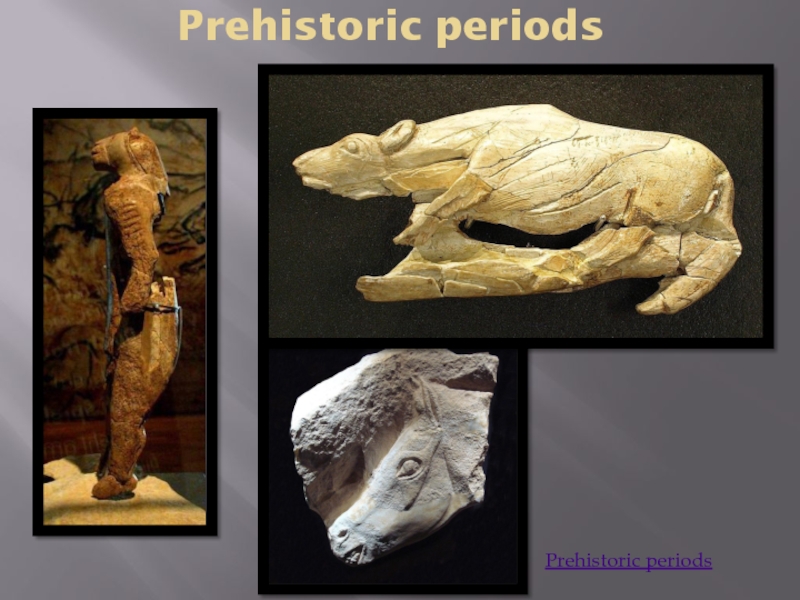

Слайд 16Prehistoric periods

The earliest undisputed examples of sculpture belong to the Aurignacian

culture, which was located in Europe and southwest Asia and

active at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic. As well as producing some of the earliest known cave art, the people of this culture developed finely-crafted stone tools, manufacturing pendants, bracelets, ivory beads, and bone-flutes, as well as three-dimensional figurines.[19][20]The 30 cm tall Löwenmensch found in the Hohlenstein Stadel area of Germany is an anthropomorphic lion-man figure carved from woolly mammoth ivory. It has been dated to about 35–40,000 BP, making it, along with the Venus of Hohle Fels, the oldest known uncontested example of figurative art.[21]

Much surviving prehistoric art is small portable sculptures, with a small group of female Venus figurines such as the Venus of Willendorf (24–26,000 BP) found across central Europe.[22] The Swimming Reindeer of about 13,000 years ago is one of the finest of a number of Magdaleniancarvings in bone or antler of animals in the art of the Upper Paleolithic, although they are outnumbered by engraved pieces, which are sometimes classified as sculpture.[23] Two of the largest prehistoric sculptures can be found at the Tuc d'Audobert caves in France, where around 12–17,000 years ago a masterful sculptor used a spatula-like stone tool and fingers to model a pair of large bison in clay against a limestone rock.[24]

With the beginning of the Mesolithic in Europe figurative sculpture greatly reduced,[25] and remained a less common element in art than relief decoration of practical objects until the Roman period, despite some works such as the Gundestrup cauldron from the European Iron Age and the Bronze Age Trundholm sun chariot.[26]

Слайд 18Ancient Egypt

The monumental sculpture of ancient Egypt is world-famous, but refined and

delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians

used the distinctive technique of sunk relief, which is well suited to very bright sunlight. The main figures in reliefs adhere to the same figure convention as in painting, with parted legs (where not seated) and head shown from the side, but the torso from the front, and a standard set of proportions making up the figure, using 18 "fists" to go from the ground to the hair-line on the forehead. This appears as early as the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I. However, there as elsewhere the convention is not used for minor figures shown engaged in some activity, such as the captives and corpses.Other conventions make statues of males darker than females ones. Very conventionalized portrait statues appear from as early as Dynasty II, before 2,780 BCE, and with the exception of the art of the Amarna period of Ahkenaten,and some other periods such as Dynasty XII, the idealized features of rulers, like other Egyptian artistic conventions, changed little until after the Greek conquest.Egyptian pharaohs were always regarded as deities, but other deities are much less common in large statues, except when they represent the pharaoh as another deity; however the other deities are frequently shown in paintings and reliefs. The famous row of four colossal statues outside the main temple at Abu Simbel each show Rameses II, a typical scheme, though here exceptionally large. Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are very common, and found in popular materials such as pottery. Most larger sculpture survives from Egyptian temples or tombs; by Dynasty IV (2680–2565 BCE) at the latest the idea of the Ka statue was firmly established. These were put in tombs as a resting place for the ka portion of the soul, and so we have a good number of less conventionalized statues of well-off administrators and their wives, many in wood as Egypt is one of the few places in the world where the climate allows wood to survive over millennia. The so-called reserve heads, plain hairless heads, are especially naturalistic. Early tombs also contained small models of the slaves, animals, buildings and objects such as boats necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterworld, and later Ushabti figures.

Слайд 20Classical

There are fewer original remains from the first phase of

the Classical period, often called the Severe style; free-standing statues were

now mostly made in bronze, which always had value as scrap. The Severe style lasted from around 500 in reliefs, and soon after 480 in statues, to about 450. The relatively rigid poses of figures relaxed, and asymmetrical turning positions and oblique views became common, and deliberately sought. This was combined with a better understanding of anatomy and the harmonious structure of sculpted figures, and the pursuit of naturalistic representation as an aim, which had not been present before. Excavations at the Temple of Zeus, Olympia since 1829 have revealed the largest group of remains, from about 460, of which many are in the Louvre.The "High Classical" period lasted only a few decades from about 450 to 400, but has had a momentous influence on art, and retains a special prestige, despite a very restricted number of original survivals. The best known works are the Parthenon Marbles, traditionally (since Plutarch) executed by a team led by the most famous ancient Greek sculptor Phidias, active from about 465–425, who was in his own day more famous for his colossal chryselephantine Statue of Zeus at Olympia (c. 432), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, his Athena Parthenos (438), the cult image of the Parthenon, and Athena Promachos, a colossal bronze figure that stood next to the Parthenon; all of these are lost but are known from many representations. He is also credited as the creator of some life-size bronze statues known only from later copies whose identification is controversial, including the Ludovisi Hermes.