Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Great Pyramid of Giza

Содержание

- 1. Great Pyramid of Giza

- 2. I.History and description Egyptologists believe the pyramid was

- 3. The first precision measurements of

- 4. The pyramid remained the tallest man-made structure in the

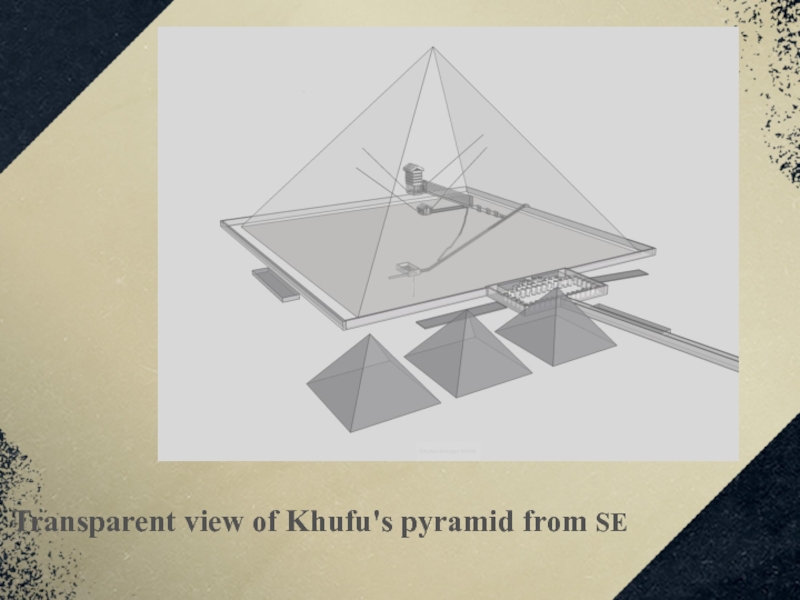

- 5. Transparent view of Khufu's pyramid from SE

- 6. Map of the Giza pyramid complex. The

- 7. II. MaterialsThe Great Pyramid consists of an

- 8. At completion, the Great Pyramid was surfaced

- 9. Nevertheless, a few of the casing stones

- 10. Many alternative, often contradictory, theories

- 11. One mystery of the pyramid's

- 12. Casing stone in the British Museum

- 13. Clay seal bearing the name of Khufu

- 14. III. Interior The original entrance

- 15. Diagram of the interior structures of the

- 16. Grand Gallery The Grand Gallery

- 17. The Grand Gallery of the Great Pyramid of Giza

- 18. King's Chamber The "King's Chamber"is

- 19. Sarcophagus in the King's chambermain pagemain

- 20. The Great Pyramid is

- 21. Remains of the floor of the temple at the east foot of the pyramid

- 22. A notable construction flanking the

- 23. Group photo of Australian 11th Battalion soldiers on the Great Pyramid in 1915.main pagemain

- 24. V. Looting Although succeeding pyramids

- 25. He adds: "If this highly speculative

- 26. VI.Video about pyramidsmain page

- 27. Thank you for your attention!!!

- 28. Скачать презентанцию

I.History and description Egyptologists believe the pyramid was built as a tomb for the Fourth Dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu (often Hellenized as "Cheops") and was constructed over a 20-year period. Khufu's vizier, Hemiunu (also called Hemon), is believed by some

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 1Great Pyramid of Giza

I.History and description

II. Materials

III. Interior

IV. Pyramid complex

V.

Looting

Слайд 2I.History and description

Egyptologists believe the pyramid was built as a tomb

for the Fourth Dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu (often Hellenized as "Cheops") and was constructed over

a 20-year period. Khufu's vizier, Hemiunu (also called Hemon), is believed by some to be the architect of the Great Pyramid. It is thought that, at construction, the Great Pyramid was originally 280 Egyptian Royal cubits tall (146.5 metres (480.6 ft)), but with erosion and the absence of its pyramidion, its present height is 138.8 metres (455.4 ft). Each base side was 440 cubits, 230.4 metres (755.9 ft) long. The mass of the pyramid is estimated at 5.9 million tonnes. The volume, including an internal hillock, is roughly 2,500,000 cubic metres (88,000,000 cu ft).Слайд 3 The first precision measurements of the pyramid were

made by Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie in 1880–82 and published as The Pyramids

and Temples of Gizeh. Almost all reports are based on his measurements. Many of the casing-stones and inner chamber blocks of the Great Pyramid fit together with extremely high precision. Based on measurements taken on the north-eastern casing stones, the mean opening of the joints is only 0.5 millimetres (0.020 in) wide.Слайд 4The pyramid remained the tallest man-made structure in the world for over

3,800 years, unsurpassed until the 160-metre-tall (520 ft) spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed

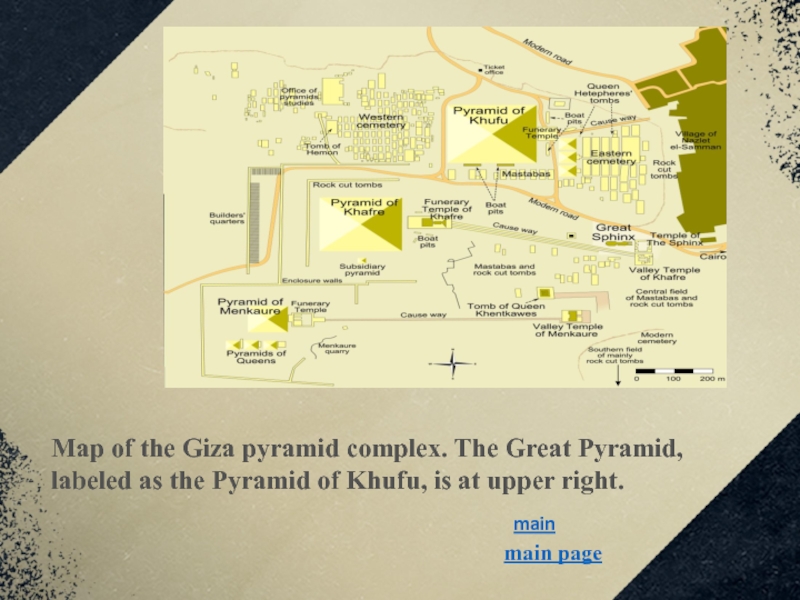

c. 1300. The accuracy of the pyramid's workmanship is such that the four sides of the base have an average error of only 58 millimetres in length. The base is horizontal and flat to within ±15 mm (0.6 in).The sides of the square base are closely aligned to the four cardinal compass points (within four minutes of arc) based on true north, not magnetic north,and the finished base was squared to a mean corner error of only 12 seconds of arc.Слайд 6Map of the Giza pyramid complex. The Great Pyramid, labeled

as the Pyramid of Khufu, is at upper right.

main page

main

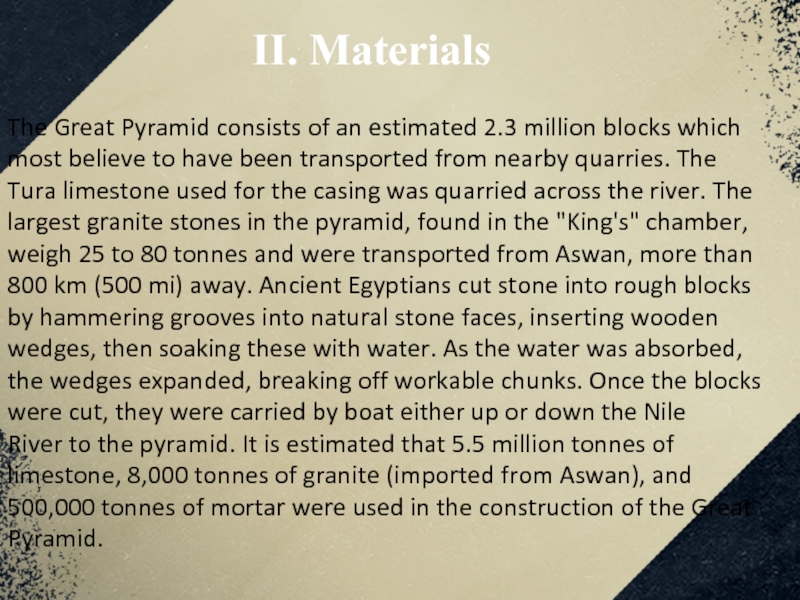

Слайд 7II. Materials

The Great Pyramid consists of an estimated 2.3 million blocks

which most believe to have been transported from nearby quarries. The

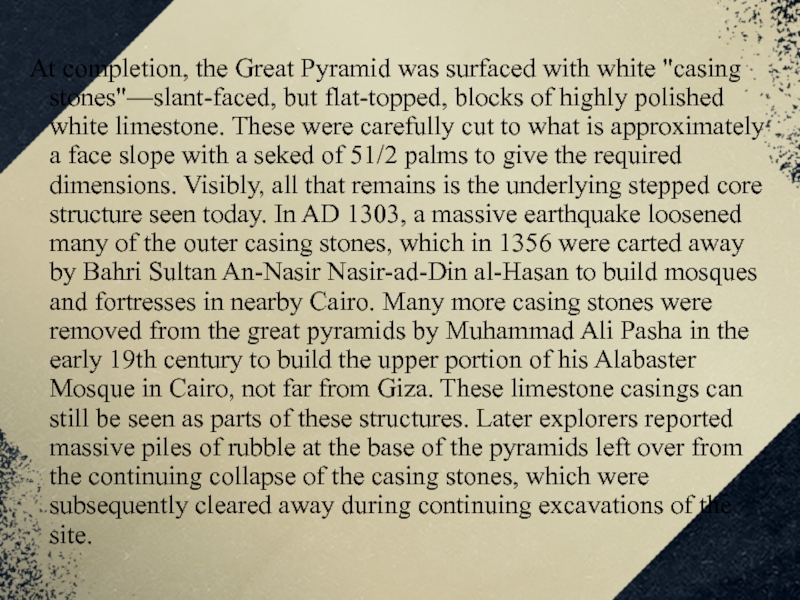

Tura limestone used for the casing was quarried across the river. The largest granite stones in the pyramid, found in the "King's" chamber, weigh 25 to 80 tonnes and were transported from Aswan, more than 800 km (500 mi) away. Ancient Egyptians cut stone into rough blocks by hammering grooves into natural stone faces, inserting wooden wedges, then soaking these with water. As the water was absorbed, the wedges expanded, breaking off workable chunks. Once the blocks were cut, they were carried by boat either up or down the Nile River to the pyramid. It is estimated that 5.5 million tonnes of limestone, 8,000 tonnes of granite (imported from Aswan), and 500,000 tonnes of mortar were used in the construction of the Great Pyramid.Слайд 8At completion, the Great Pyramid was surfaced with white "casing

stones"—slant-faced, but flat-topped, blocks of highly polished white limestone. These

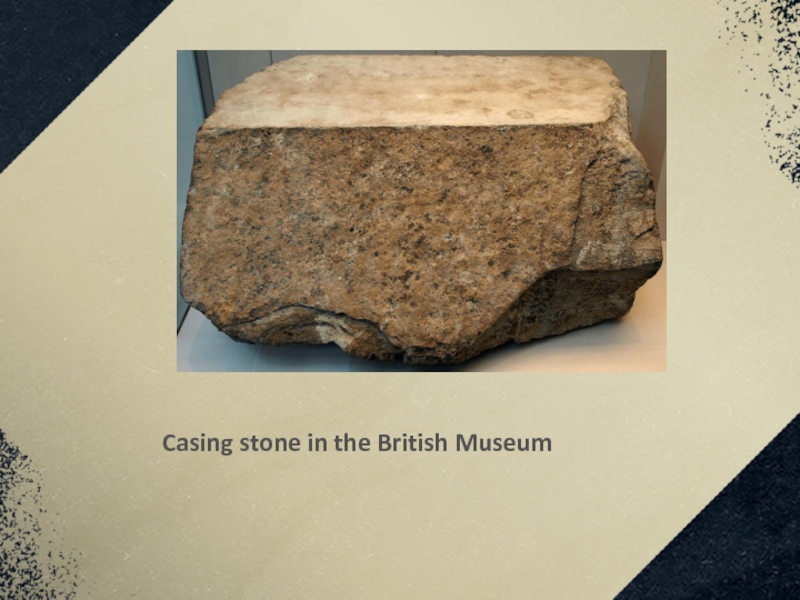

were carefully cut to what is approximately a face slope with a seked of 51/2 palms to give the required dimensions. Visibly, all that remains is the underlying stepped core structure seen today. In AD 1303, a massive earthquake loosened many of the outer casing stones, which in 1356 were carted away by Bahri Sultan An-Nasir Nasir-ad-Din al-Hasan to build mosques and fortresses in nearby Cairo. Many more casing stones were removed from the great pyramids by Muhammad Ali Pasha in the early 19th century to build the upper portion of his Alabaster Mosque in Cairo, not far from Giza. These limestone casings can still be seen as parts of these structures. Later explorers reported massive piles of rubble at the base of the pyramids left over from the continuing collapse of the casing stones, which were subsequently cleared away during continuing excavations of the site.Слайд 9Nevertheless, a few of the casing stones from the lowest

course can be seen to this day in situ around the base

of the Great Pyramid, and display the same workmanship and precision that has been reported for centuries. Petrie also found a different orientation in the core and in the casing measuring 193 centimetres ± 25 centimetres. He suggested a redetermination of north was made after the construction of the core, but a mistake was made, and the casing was built with a different orientation.Petrie related the precision of the casing stones as to being "equal to opticians' work of the present day, but on a scale of acres" and "to place such stones in exact contact would be careful work; but to do so with cement in the joints seems almost impossible". It has been suggested it was the mortar (Petrie's "cement") that made this seemingly impossible task possible, providing a level bed, which enabled the masons to set the stones exactly.Слайд 10 Many alternative, often contradictory, theories have been proposed

regarding the pyramid's construction techniques.Many disagree on whether the blocks

were dragged, lifted, or even rolled into place. The Greeks believed that slave labour was used, but modern discoveries made at nearby workers' camps associated with construction at Giza suggest that it was built instead by tens of thousands of skilled workers. Verner posited that the labour was organized into a hierarchy, consisting of two gangs of 100,000 men, divided into five zaa or phyle of 20,000 men each, which may have been further divided according to the skills of the workers.Слайд 11 One mystery of the pyramid's construction is its

planning. John Romer suggests that they used the same method that had

been used for earlier and later constructions, laying out parts of the plan on the ground at a 1-to-1 scale. He writes that "such a working diagram would also serve to generate the architecture of the pyramid with precision unmatched by any other means". He also argues for a 14-year time-span for its construction. A modern construction management study, in association with Mark Lehner and other Egyptologists, estimated that the total project required an average workforce of about 14,500 people and a peak workforce of roughly 40,000. Without the use of pulleys, wheels, or iron tools, they used critical path analysis methods, which suggest that the Great Pyramid was completed from start to finish in approximately 10 years.Слайд 13Clay seal bearing the name of Khufu from the Great

Pyramid on display at the Musée du Louvre

main page

main

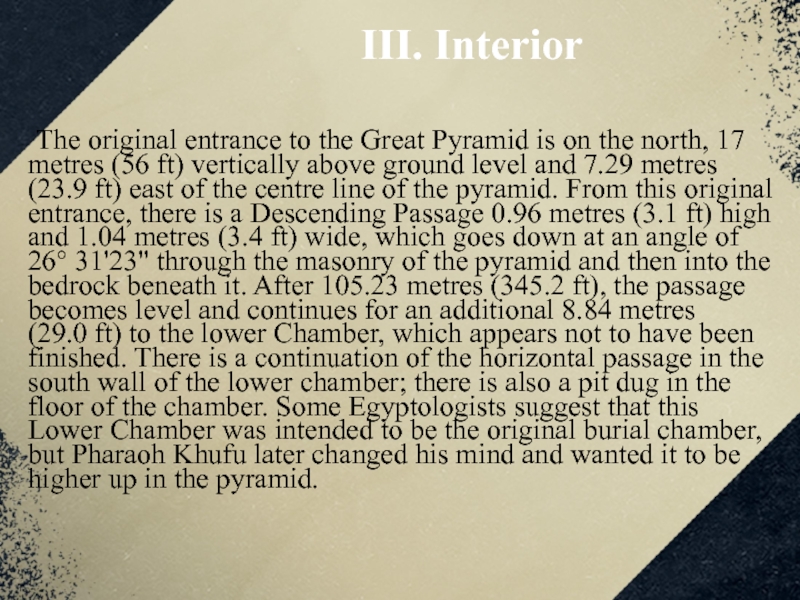

Слайд 14III. Interior

The original entrance to the Great Pyramid

is on the north, 17 metres (56 ft) vertically above ground

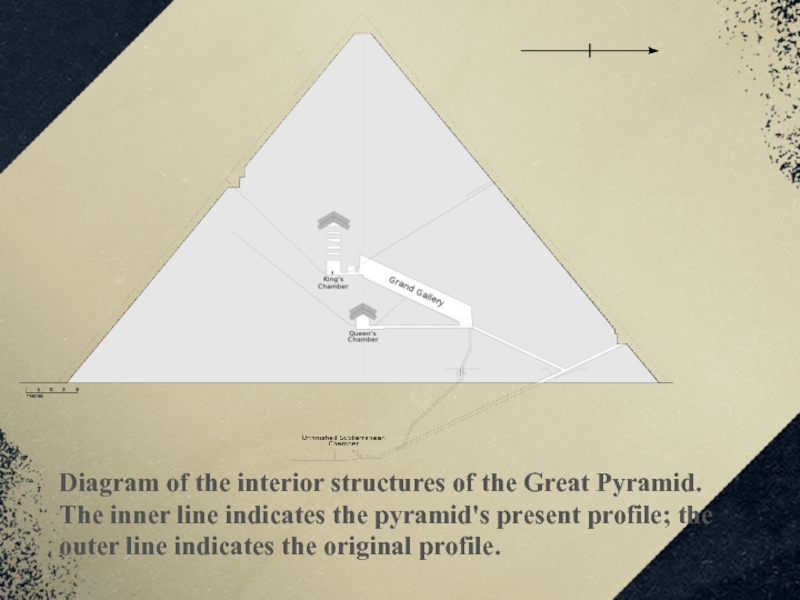

level and 7.29 metres (23.9 ft) east of the centre line of the pyramid. From this original entrance, there is a Descending Passage 0.96 metres (3.1 ft) high and 1.04 metres (3.4 ft) wide, which goes down at an angle of 26° 31'23" through the masonry of the pyramid and then into the bedrock beneath it. After 105.23 metres (345.2 ft), the passage becomes level and continues for an additional 8.84 metres (29.0 ft) to the lower Chamber, which appears not to have been finished. There is a continuation of the horizontal passage in the south wall of the lower chamber; there is also a pit dug in the floor of the chamber. Some Egyptologists suggest that this Lower Chamber was intended to be the original burial chamber, but Pharaoh Khufu later changed his mind and wanted it to be higher up in the pyramid.Слайд 15Diagram of the interior structures of the Great Pyramid. The

inner line indicates the pyramid's present profile; the outer line

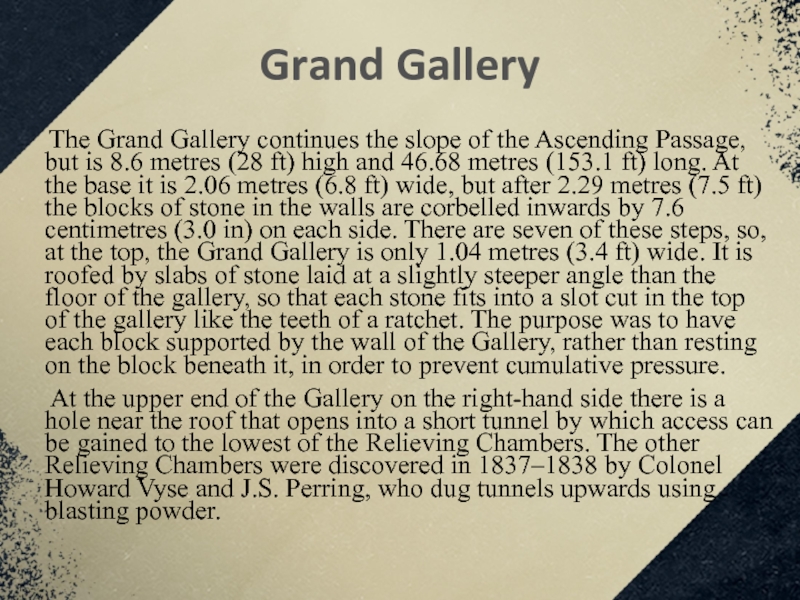

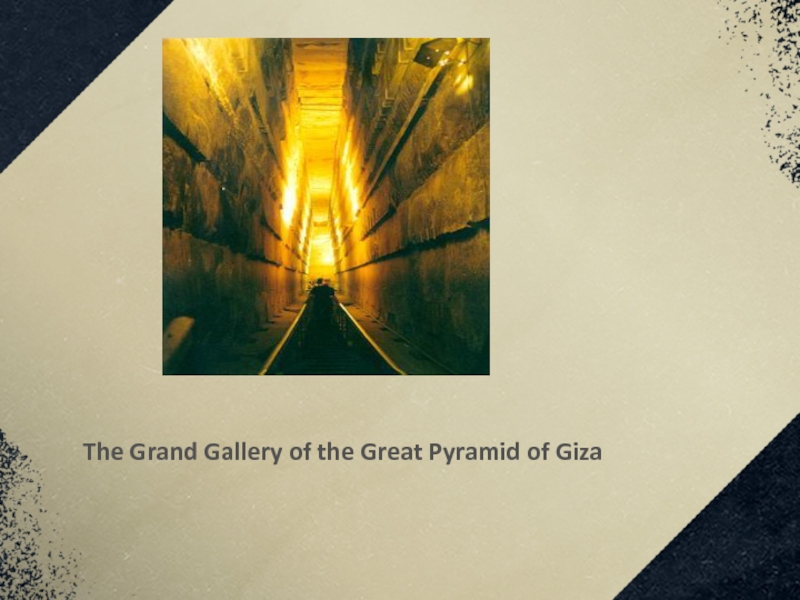

indicates the original profile.Слайд 16Grand Gallery

The Grand Gallery continues the slope of

the Ascending Passage, but is 8.6 metres (28 ft) high and

46.68 metres (153.1 ft) long. At the base it is 2.06 metres (6.8 ft) wide, but after 2.29 metres (7.5 ft) the blocks of stone in the walls are corbelled inwards by 7.6 centimetres (3.0 in) on each side. There are seven of these steps, so, at the top, the Grand Gallery is only 1.04 metres (3.4 ft) wide. It is roofed by slabs of stone laid at a slightly steeper angle than the floor of the gallery, so that each stone fits into a slot cut in the top of the gallery like the teeth of a ratchet. The purpose was to have each block supported by the wall of the Gallery, rather than resting on the block beneath it, in order to prevent cumulative pressure.At the upper end of the Gallery on the right-hand side there is a hole near the roof that opens into a short tunnel by which access can be gained to the lowest of the Relieving Chambers. The other Relieving Chambers were discovered in 1837–1838 by Colonel Howard Vyse and J.S. Perring, who dug tunnels upwards using blasting powder.

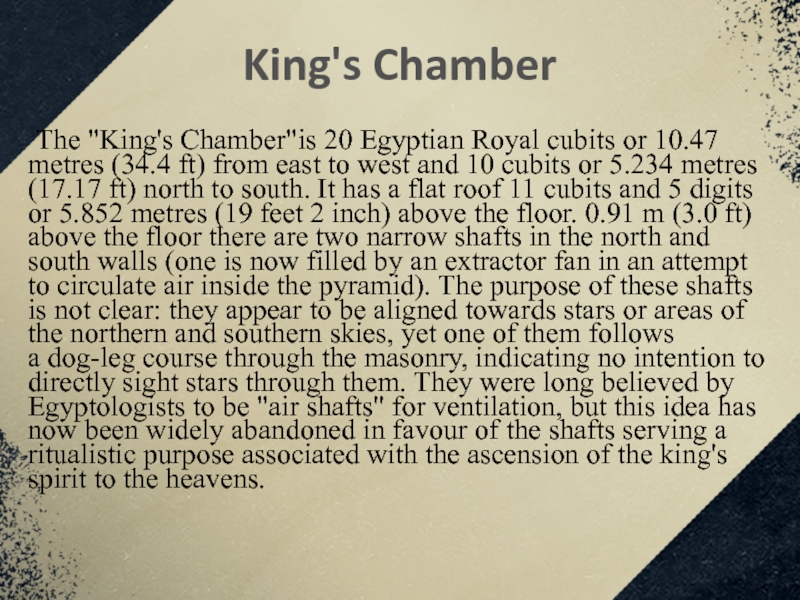

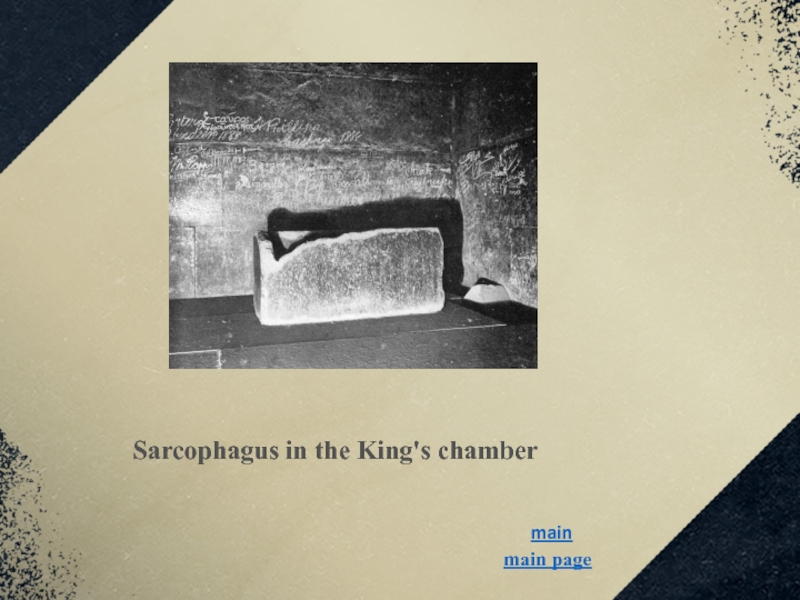

Слайд 18King's Chamber

The "King's Chamber"is 20 Egyptian Royal cubits

or 10.47 metres (34.4 ft) from east to west and 10

cubits or 5.234 metres (17.17 ft) north to south. It has a flat roof 11 cubits and 5 digits or 5.852 metres (19 feet 2 inch) above the floor. 0.91 m (3.0 ft) above the floor there are two narrow shafts in the north and south walls (one is now filled by an extractor fan in an attempt to circulate air inside the pyramid). The purpose of these shafts is not clear: they appear to be aligned towards stars or areas of the northern and southern skies, yet one of them follows a dog-leg course through the masonry, indicating no intention to directly sight stars through them. They were long believed by Egyptologists to be "air shafts" for ventilation, but this idea has now been widely abandoned in favour of the shafts serving a ritualistic purpose associated with the ascension of the king's spirit to the heavens.Слайд 20

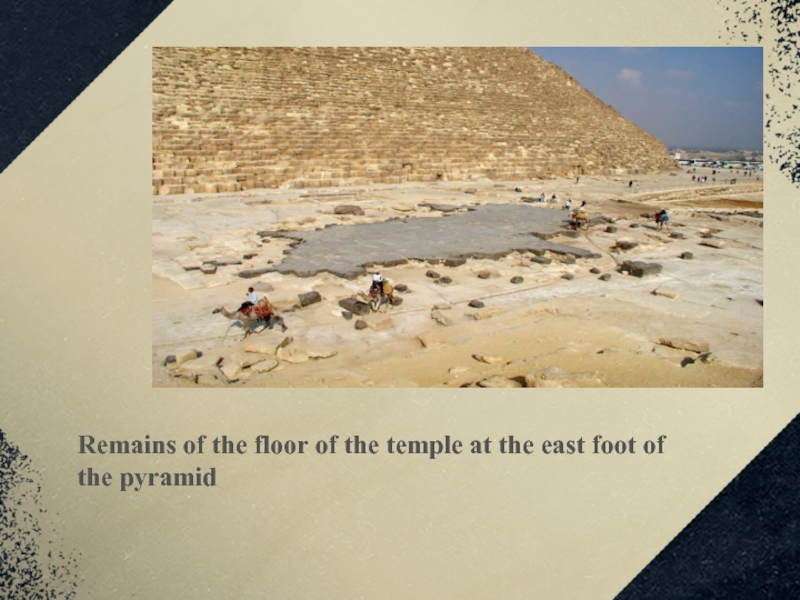

The Great Pyramid is surrounded by a complex

of several buildings including small pyramids. The Pyramid Temple, which

stood on the east side of the pyramid and measured 52.2 metres (171 ft) north to south and 40 metres (130 ft) east to west, has almost entirely disappeared apart from the black basalt paving. There are only a few remnants of the causeway which linked the pyramid with the valley and the Valley Temple. The Valley Temple is buried beneath the village of Nazlet el-Samman; basalt paving and limestone walls have been found but the site has not been excavated.The basalt blocks show "clear evidence" of having been cut with some kind of saw with an estimated cutting blade of 15 feet (4.6 m) in length, capable of cutting at a rate of 1.5 inches (38 mm) per minute. Romer suggests that this "super saw" may have had copper teeth and weighed up to 300 pounds (140 kg). He theorizes that such a saw could have been attached to a wooden trestle and possibly used in conjunction with vegetable oil, cutting sand, emery or pounded quartz to cut the blocks, which would have required the labour of at least a dozen men to operate it.IV. Pyramid complex

Слайд 22 A notable construction flanking the Giza pyramid complex

is a cyclopean stone wall, the Wall of the Crow.[Lehner has discovered

a worker's town outside of the wall, otherwise known as "The Lost City", dated by pottery styles, seal impressions, and stratigraphy to have been constructed and occupied sometime during the reigns of Khafre (2520–2494 BC) and Menkaure (2490–2472 BC). In the early 21st century, Mark Lehner and his team made several discoveries, including what appears to have been a thriving port, suggesting the town and associated living quarters, which consisted of barracks called "galleries", may not have been for the pyramid workers after all but rather for the soldiers and sailors who utilized the port. In light of this new discovery, as to where then the pyramid workers may have lived, Lehner suggested the alternative possibility they may have camped on the ramps he believes were used to construct the pyramids or possibly at nearby quarries.Слайд 23Group photo of Australian 11th Battalion soldiers on the Great Pyramid in

1915.

main page

main

Слайд 24V. Looting

Although succeeding pyramids were smaller, pyramid-building continued

until the end of the Middle Kingdom. However, as authors Brier

and Hobbs claim, "all the pyramids were robbed" by the New Kingdom, when the construction of royal tombs in a desert valley, now known as the Valley of the Kings. Tyldesley states that the Great Pyramid itself "is known to have been opened and emptied by the Middle Kingdom", before the Arab caliph Al-Ma'mun entered the pyramid around AD 820.I.E.S. Edwards discusses Strabo's mention that the pyramid "a little way up one side has a stone that may be taken out, which being raised up there is a sloping passage to the foundations". Edwards suggested that the pyramid was entered by robbers after the end of the Old Kingdom and sealed and then reopened more than once until Strabo's door was added. .

Слайд 25 He adds: "If this highly speculative surmise be correct,

it is also necessary to assume either that the existence

of the door was forgotten or that the entrance was again blocked with facing stones", in order to explain why al-Ma'mun could not find the entrance He also discusses a story told by Herodotus. Herodotus visited Egypt in the 5th century BC and recounts a story that he was told concerning vaults under the pyramid built on an island where the body of Cheops lies. Edwards notes that the pyramid had "almost certainly been opened and its contents plundered long before the time of Herodotus" and that it might have been closed again during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt when other monuments were restored. He suggests that the story told to Herodotus could have been the result of almost two centuries of telling and retelling by Pyramid guides.main page

main