Слайд 1The Introduction of Printing

Выполнила Жуйкова София, группа ПП/с-18-1-2

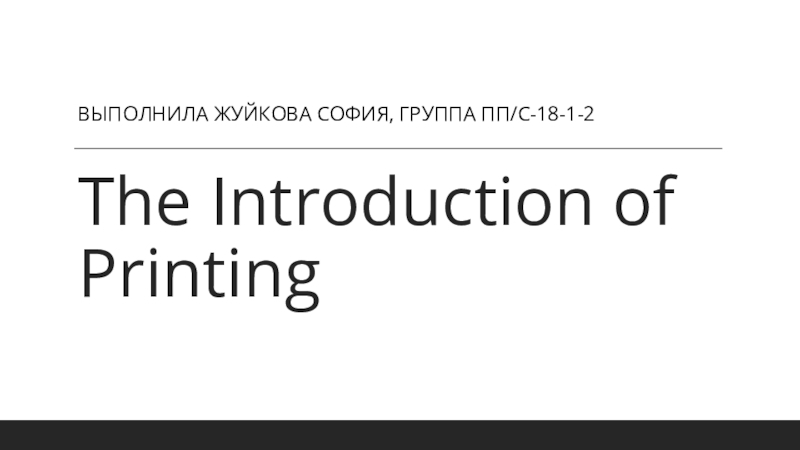

Слайд 2The Printing Press

Printing with moveable type was introduced to the Western

world in the 1450s by Johann Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany.

Gutenberg invented the printing press: this new print technology involved setting pages of type from individually cast metal letter forms that were then run off on a hand press. For the first time it was possible to rapidly and mechanically reproduce multiple copies of the same work. This new technology heralded the beginnings of a massive cultural revolution. Before Gutenberg’s invention, books were usually copied by hand, in manuscript, a laborious and cost-intensive process. The potentialities of Gutenberg’s machine were quickly grasped and printing spread rapidly throughout Europe in the second half of the 15th century.

Слайд 3The advent of printing in England was due to the

efforts of William Caxton, who was born, probably in Kent,

between 1415 and 1424. He was apprenticed to a member of the Mercers’ Company in London and subsequently worked for much of his adult life as an English merchant in the Low Countries, particularly in Bruges, where he became governor of the resident English merchants. Caxton’s commercial experience must have made him quick to see the potential of print.

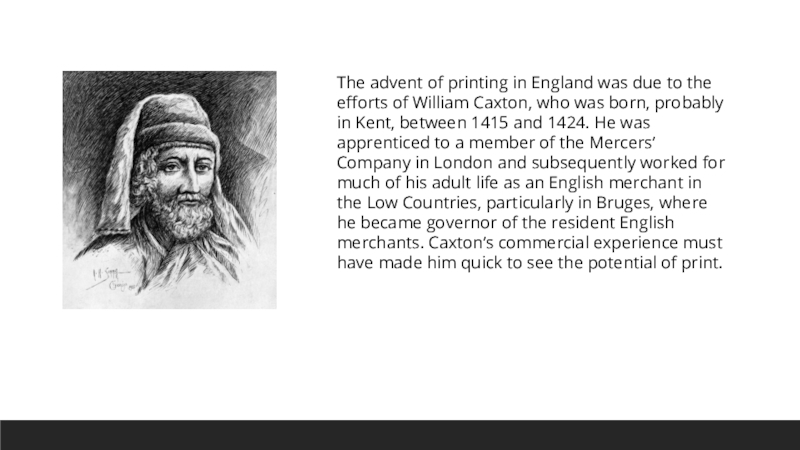

Слайд 4Caxton learns to print

Caxton seems to have learnt how to

print in Cologne, in what is now Germany. The first

evidence of his interest in this new technology was his involvement in the printing there, in 1472, of a massive Latin encyclopaedic work, Bartholomaeus Anglicus’s De Proprietatibus Rerum [‘On the Properties of Things’]. Wynkyn de Worde, Caxton’s associate and successor, who printed an English translation of Bartholomaeus in Westminster in 1495/96, says in the verse epilogue to it that ‘William Caxton [was] first printer of this book in Latin tongue at Cologne’. In fact, the Cologne edition was probably undertaken by a German printer, possibly Johannes Schilling, who organised the production of this book for Caxton and instructed him in the techniques of printing while he was resident there. It is possible that Caxton published other books while in Cologne, but the evidence is not conclusive.

Слайд 5Subsequently, Caxton applied the experience he had gained in Cologne

by printing various books in the Low Countries. He seems

to have published the first book in English in Ghent, in around 1473. This was his own translation of the Recuyell of the Histories of Troy, an account of the Trojan legend. Caxton states in the preface that he had completed the translation while he was in Cologne in September 1471. In the following year he printed another of his own English translations, the Game of Chess. In Bruges, in 1475, he printed a few more books.

Слайд 6Caxton brings printing to England

In around 1476 Caxton returned to

England and set up the first printing shop in the

country near Westminster Cathedral. From here he issued over a hundred books between 1476 and 1492, the year of his death. The size of his organisation is unclear. But since from early in his career he had been publishing large books he must have had a number of workmen to undertake the various aspects of printing, including typesetting, operating the press, proofreading and binding.

Слайд 7The great majority of these books were written in English,

although a few were in Latin. One of the first

major books he printed, in 1477, was Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Caxton was evidently keen to make available to his readers the writings of the most widely known of medieval English poets. He printed a second edition of The Canterbury Tales in 1483, as well as other poems by Chaucer: his Parliament of Fowls and Anelida and Arcite (both c. 1477–78), and his Troilus and Criseyde and House of Fame, both in 1483. He also printed Chaucer’s prose translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy (1478). Thus Caxton established the tradition of Chaucer in print that has continued over the centuries.

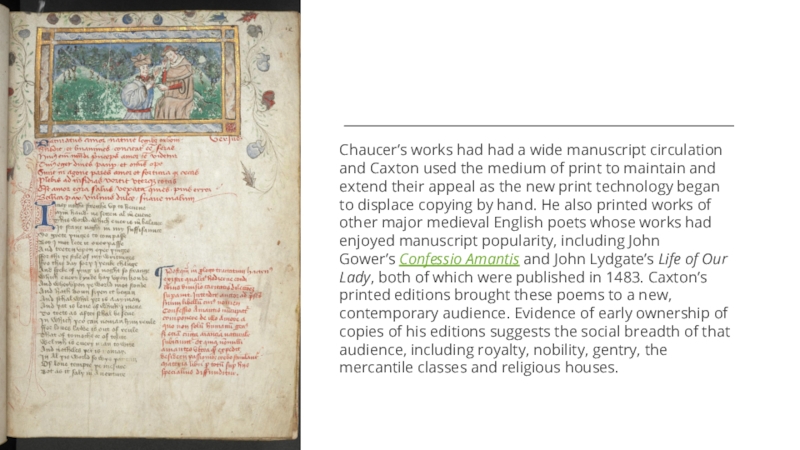

Слайд 8Chaucer’s works had had a wide manuscript circulation and Caxton

used the medium of print to maintain and extend their

appeal as the new print technology began to displace copying by hand. He also printed works of other major medieval English poets whose works had enjoyed manuscript popularity, including John Gower’s Confessio Amantis and John Lydgate’s Life of Our Lady, both of which were published in 1483. Caxton’s printed editions brought these poems to a new, contemporary audience. Evidence of early ownership of copies of his editions suggests the social breadth of that audience, including royalty, nobility, gentry, the mercantile classes and religious houses.

Слайд 9However, most of the books Caxton printed in English were

in prose. Once more, some of these reflected earlier traditions

of manuscript popularity. Thus, he made available in print for the first time such popular historical writings as the prose Brut, a chronicle of English history, that he printed in 1480 and again in 1482, and an English translation of a Latin universal history, the Polychronicon, published in 1482; both of these works had previously circulated widely in manuscript.

Слайд 10 He also printed English religious works that had enjoyed a

similar earlier manuscript appeal, including editions of Nicholas Love’s early

15th-century Speculum vitae Christi [‘Mirror of the Life of Christ’] in 1484 and 1490, the Pilgrimage of the Soul (in 1483) and editions of various sermon collections, including two of the Festial of John Mirk (in 1483 and 1491), which was printed with the Quattuor Sermones [‘Four Sermons’]. The largest religious work Caxton printed was a collection of prose saints’ lives, The Golden Legend, in 1483. The final works from his press included several concerned with spiritual well-being: The Art and Craft to Know Well to Die (1490), The Craft for to Die Well (1491) and a collection of spiritual writings generally known as The Book of Divers Ghostly [i.e. spiritual] Matters (1491).

Слайд 11Creating new reading markets

But Caxton was not content to simply

draw on pre-existing markets for manuscripts for his readership. He

also used print to create new markets for novel and different kinds of writing. His most sustained effort of this kind was the publication of a series of prose romances, essentially a new literary form in England in the later 15th century. The most famous work of this kind was his edition of Thomas Malory’s prose Arthurian romance, Le Morte Darthur (1485), one of the biggest books his press produced. He printed a number of other romances of this kind, all in his own translations, including Godfrey of Boulogne (1481), The Knight of the Tower (1484), Charles the Great and Paris and Vienne (both in 1485) and Blanchardin and Eglantine and The Four Sons of Aymon (both in 1490).

Слайд 12Caxton's translations

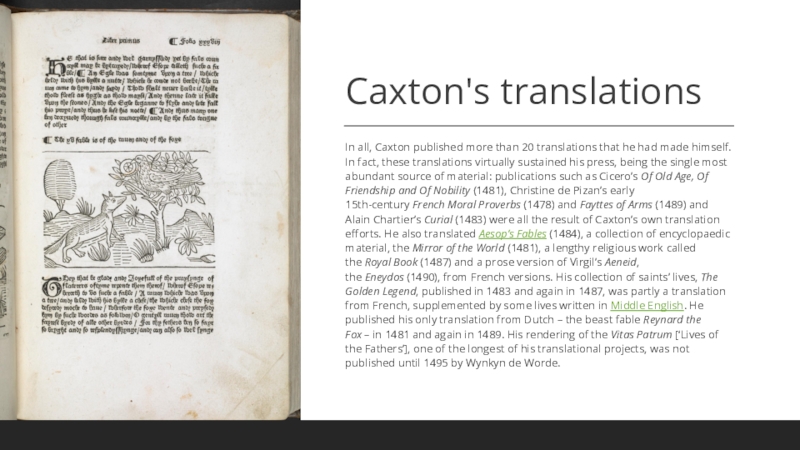

In all, Caxton published more than 20 translations that

he had made himself. In fact, these translations virtually sustained

his press, being the single most abundant source of material: publications such as Cicero’s Of Old Age, Of Friendship and Of Nobility (1481), Christine de Pizan’s early 15th-century French Moral Proverbs (1478) and Fayttes of Arms (1489) and Alain Chartier’s Curial (1483) were all the result of Caxton’s own translation efforts. He also translated Aesop’s Fables (1484), a collection of encyclopaedic material, the Mirror of the World (1481), a lengthy religious work called the Royal Book (1487) and a prose version of Virgil’s Aeneid, the Eneydos (1490), from French versions. His collection of saints’ lives, The Golden Legend, published in 1483 and again in 1487, was partly a translation from French, supplemented by some lives written in Middle English. He published his only translation from Dutch – the beast fable Reynard the Fox – in 1481 and again in 1489. His rendering of the Vitas Patrum [‘Lives of the Fathers’], one of the longest of his translational projects, was not published until 1495 by Wynkyn de Worde.

Слайд 13Caxton’s cultural and historical impact

It has been estimated that Caxton

published over three million words of his own writings during

his career, either in direct translation or in passages he added to books he printed. His own prose made important contributions to the English language, including the introduction of a large number of new words into the lexicon: his writings provide the first recorded use of such nouns as ‘concussion’, ‘fortification’, ‘servitude’ and ‘voyager’ for example. In all, he provides the first usage of over 1,300 words.

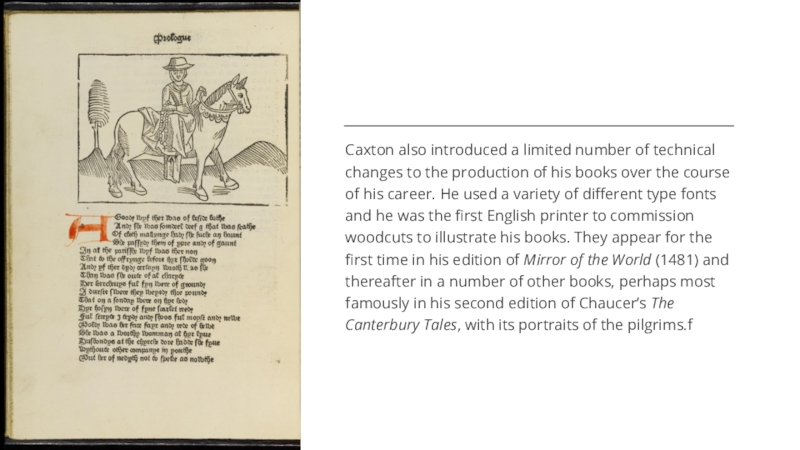

Слайд 14Caxton also introduced a limited number of technical changes to

the production of his books over the course of his

career. He used a variety of different type fonts and he was the first English printer to commission woodcuts to illustrate his books. They appear for the first time in his edition of Mirror of the World (1481) and thereafter in a number of other books, perhaps most famously in his second edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, with its portraits of the pilgrims.f

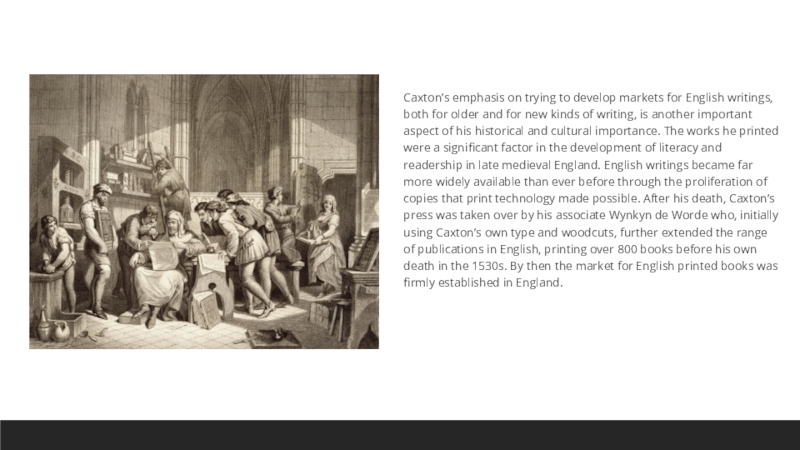

Слайд 15Caxton’s emphasis on trying to develop markets for English writings,

both for older and for new kinds of writing, is

another important aspect of his historical and cultural importance. The works he printed were a significant factor in the development of literacy and readership in late medieval England. English writings became far more widely available than ever before through the proliferation of copies that print technology made possible. After his death, Caxton’s press was taken over by his associate Wynkyn de Worde who, initially using Caxton’s own type and woodcuts, further extended the range of publications in English, printing over 800 books before his own death in the 1530s. By then the market for English printed books was firmly established in England.