Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

European Integration History: Phases, Results and Achievements. Political

Содержание

- 1. European Integration History: Phases, Results and Achievements. Political

- 2. 1.2. European Idea and Phases of European

- 3. The first attempts to achieve unity by

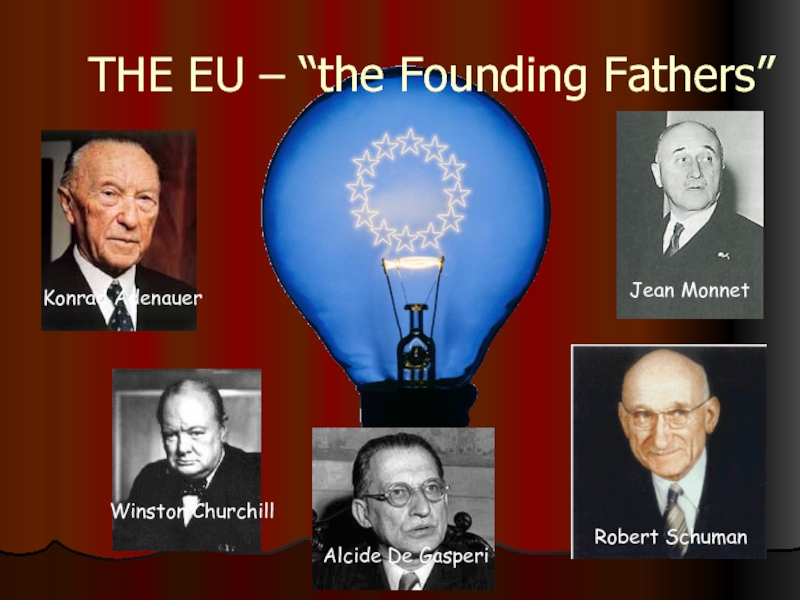

- 4. THE EU – “the Founding Fathers”

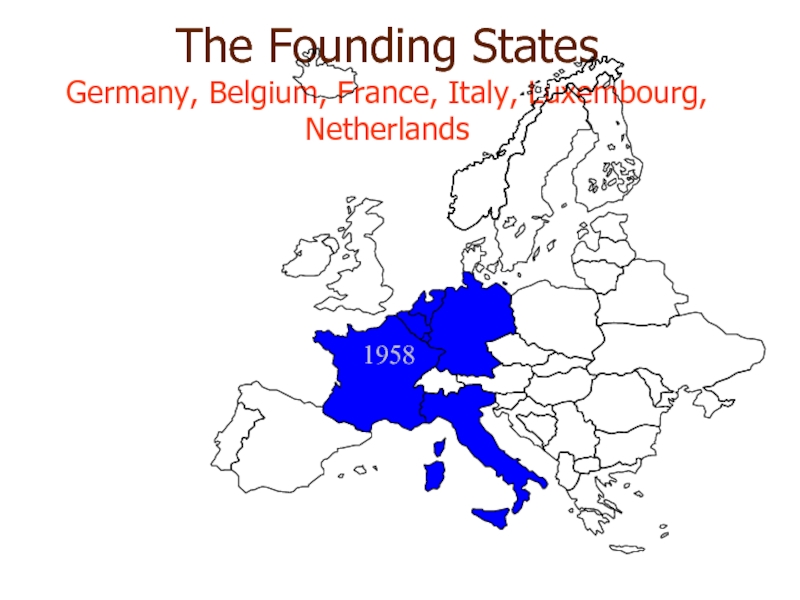

- 5. The Founding States Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands 1958

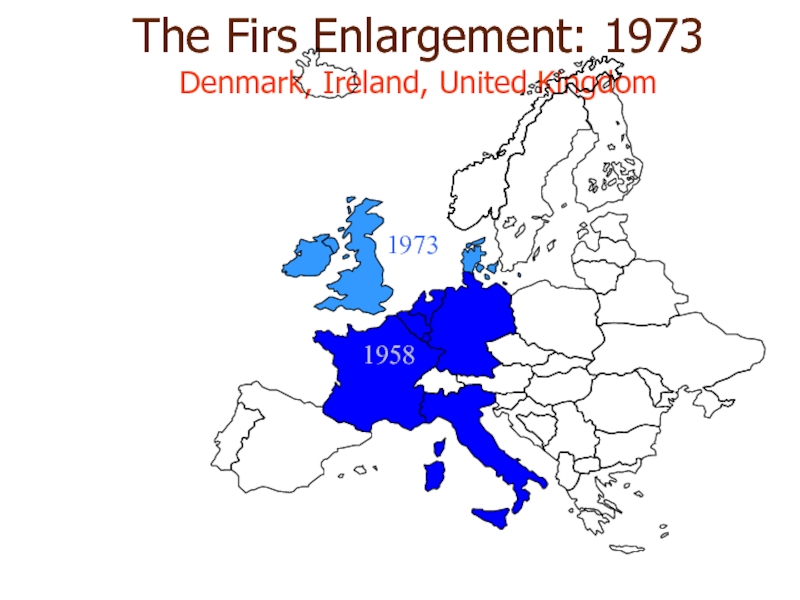

- 6. The Firs Enlargement: 1973 Denmark, Ireland, United Kingdom19581973

- 7. The Second Enlargement: 1981 Greece195819731981

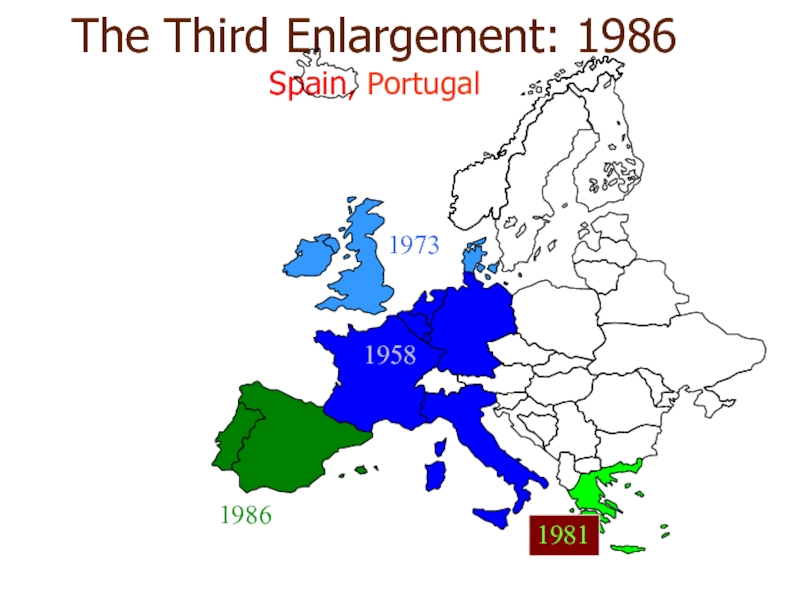

- 8. The Third Enlargement: 1986 Spain, Portugal1958197319861981

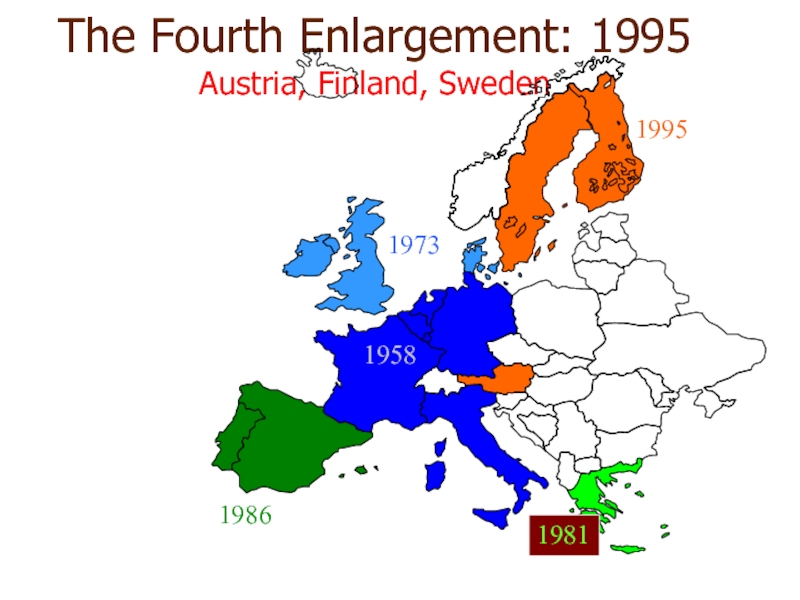

- 9. The Fourth Enlargement: 1995 Austria, Finland, Sweden19581973199519861981

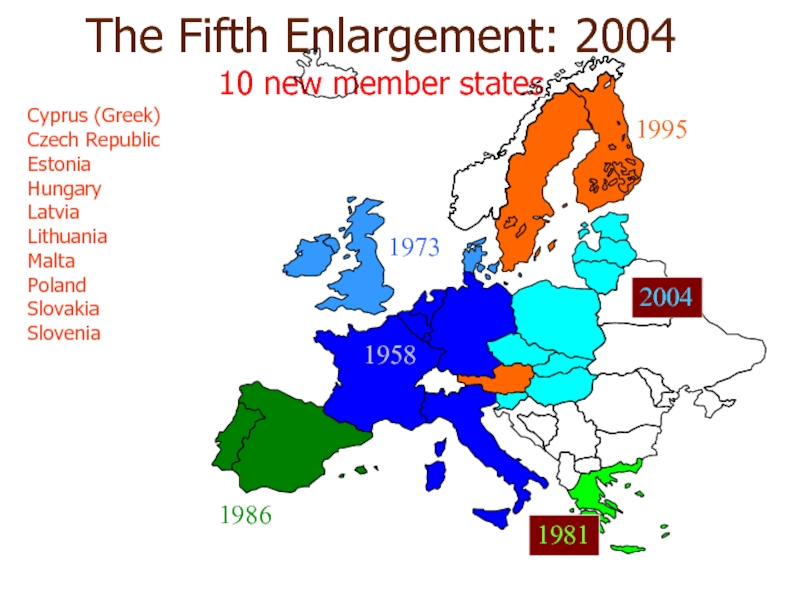

- 10. The Fifth Enlargement: 2004 10 new member states195819731995200419861981Cyprus (Greek)Czech RepublicEstoniaHungaryLatviaLithuaniaMaltaPolandSlovakiaSlovenia

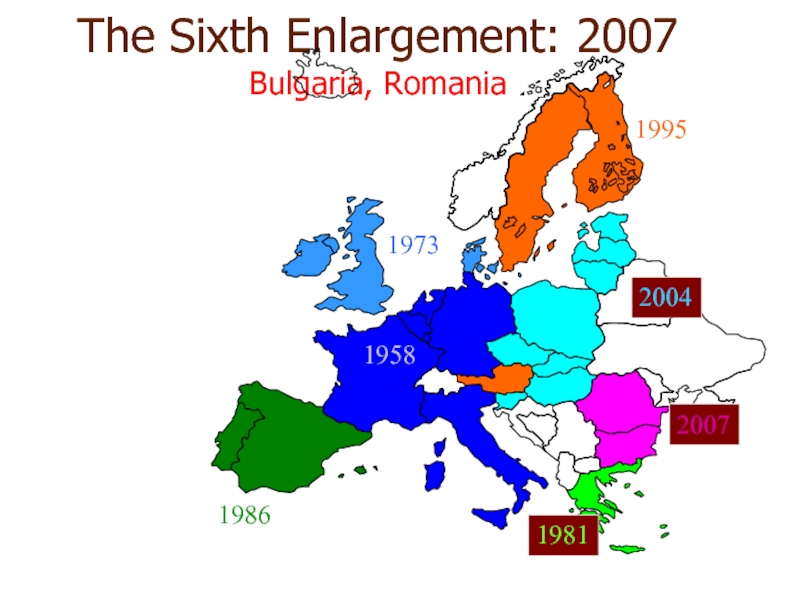

- 11. The Sixth Enlargement: 2007 Bulgaria, Romania1958197319952004198619812007

- 12. THE EU – COMMON CULTURAL ROOTS

- 13. CONSOLIDATED VERSION OF THE TREATY ON EUROPEAN

- 14. Article 31. The Union’s aim is to

- 15. 3. The Union shall establish an internal

- 16. 4. The Union shall establish an economic

- 17. Цінності ЄССоюз засновано на цінностях поваги до

- 18. Цілі ЄС• Забезпечувати людям простір свободи, безпеки

- 19. Цілі ЄС (продовження)• Сприяти економічній, соціальній та

- 20. The EUEconomy: equality of resultshigh level of

- 21. The EUhas moved into a world of

- 22. Explaining the EU todayThe EU today sits

- 23. The Evolution of the EU Phases1. First

- 24. First steps towards integration (1945-1958)

- 25. The priority for European leaders after the

- 26. Western European governments quickly realized that changes

- 27. It soon became clear that substantial capital

- 28. In June 1948 three zones of occupation

- 29. National pro-European groups decided to organize a

- 30. The critical first step was taken on

- 31. The European Coal and Steel Community was

- 32. European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was

- 33. The European Economic Community (1958-1986)

- 34. A new round of negotiations led to

- 35. The EEC Treaty committed the Six to

- 36. Decision making was streamlined in April 1965

- 37. Although the 12-year deadline for the creation

- 38. Britain was not opposed to European cooperation,

- 39. The doubling of membership had several political

- 40. Economic and social integration (1979-1992)

- 41. By 1986 the EEC had become known

- 42. In 1979, a new initiative was launched

- 43. Meanwhile there was concern that progress towards

- 44. The effects of the SEA were profound:

- 45. It created the single biggest market and

- 46. It gave new powers to the European

- 47. Despite the signing of the SEA, progress

- 48. New attention was drawn to social policy

- 49. From Community to Union (1992-2009)

- 50. The outcome of this phase was the

- 51. Like the Single European Act before it,

- 52. Reflecting the lengths to which the member

- 53. The EU according to the Maastricht Treaty

- 54. A timetable was agreed for the creation

- 55. New rights were provided for European citizens

- 56. Meanwhile enlargement was still on the agenda,

- 57. Partly in preparation for anticipated eastern enlargement,

- 58. The key goal of the Treaty of

- 59. Further challenges, further changes (2009- )

- 60. At the Laeken European Council in December

- 61. The popular expectation being that the treaty

- 62. The negative votes led to widespread predictions

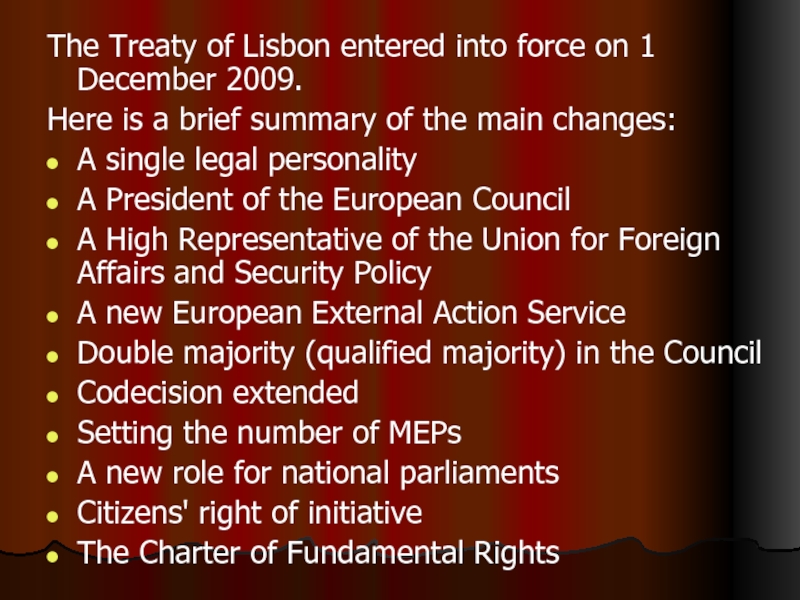

- 63. The Treaty of Lisbon entered into force

- 64. The History of the European Union (European

- 65. Скачать презентанцию

1.2. European Idea and Phases of European Integration.European Idea and its DevelopmentThe changing identity of EuropeWhere is Europe?The Meaning of Europe

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 1European Integration History: Phases, Results and Achievements. Political Challenges of the EU

Слайд 21.2. European Idea and Phases of European Integration.

European Idea and

its Development

The changing identity of Europe

Where is Europe?

The Meaning of

EuropeСлайд 3The first attempts to achieve unity by force in modern

times was made by Napoleon, who brought what are now

France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, parts of Germany and Italy.Слайд 10The Fifth Enlargement: 2004

10 new member states

1958

1973

1995

2004

1986

1981

Cyprus (Greek)

Czech Republic

Estonia

Hungary

Latvia

Lithuania

Malta

Poland

Slovakia

Slovenia

Слайд 13CONSOLIDATED VERSION OF THE TREATY ON EUROPEAN UNION N 30.3.2010

Official Journal of the European Union C 83/13

Article 2

The Union

is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.Слайд 14Article 3

1. The Union’s aim is to promote peace, its

values and the well-being of its peoples.

2. The Union shall

offer its citizens an area of freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers, in which the free movement of persons is ensured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, immigration and the prevention and combating of crime.Слайд 153. The Union shall establish an internal market. It shall

work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced

economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment. It shall promote scientific and technological advance.It shall combat social exclusion and discrimination, and shall promote social justice and protection, equality between women and men, solidarity between generations and protection of the rights of the child.

It shall promote economic, social and territorial cohesion, and solidarity among Member States.

It shall respect its rich cultural and linguistic diversity, and shall ensure that Europe’s cultural heritage is safeguarded and enhanced.

Слайд 164. The Union shall establish an economic and monetary union

whose currency is the euro.

5. In its relations with the

wider world, the Union shall uphold and promote its values and interests and contribute to the protection of its citizens. It shall contribute to peace, security, the sustainable development of the Earth, solidarity and mutual respect among peoples, free and fair trade, eradication of poverty and the protection of human rights, in particular the rights of the child, as well as to the strict observance and the development of international law, including respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter.6. The Union shall pursue its objectives by appropriate means commensurate with the competences which are conferred upon it in the Treaties.

Слайд 17Цінності ЄС

Союз засновано на цінностях поваги до людської гідності, свободи,

демократії, рівності, верховенства права та поваги до прав людини, зокрема

осіб, що належать до меншин.Ці цінності є спільними для всіх держав-членів у суспільстві, де панує плюралізм, недискримінація, толерантність, правосуддя, солідарність та рівність жінок і чоловіків.

Слайд 18Цілі ЄС

• Забезпечувати людям простір свободи, безпеки та правосуддя без

внутрішніх кордонів.

• Працювати задля сталого розвитку Європи на основі збалансованого

економічного зростання та стабільності цін, високо конкурентоспроможної соціальної ринкової економіки, спрямованої на повну зайнятість та соціальний прогрес з високим рівнем захисту навколишнього середовища.• Боротися проти соціального відчуження та дискримінації, сприяти соціальній справедливості та соціальному захисту.

Слайд 19Цілі ЄС (продовження)

• Сприяти економічній, соціальній та територіальній згуртованості та

солідарності держав-членів.

• Залишатися відданим економічному та валютному союзу з єдиною

валютою євро.• Підтримувати та поширювати цінності Європейського Союзу за його межами та робити свій внесок у мир, безпеку, сталий розвиток Землі, солідарність та взаємоповагу серед народів, вільну та чесну торгівлю та подолання бідності.

• Робити внесок у захист прав людини, зокрема прав дитини, а також суворо дотримуватися та розвивати міжнародне право, зокрема дотримання принципів Хартії ООН.

Слайд 20The EU

Economy: equality of results

high level of tolerance for government

intervention in the marketplace

Sustainable development, quality of life, community

The US

Economy:

equality of opportunityliberal economy

Economic growth, personal wealth, individual self-interest

Слайд 21The EU

has moved into a world of laws, rules, international

cooperation

sees the world as a complex global system, prefers to

negotiate and persuade rather than to coercesoft power (encouragement and opportunity)

The US

believes that security and defence depend on the possession and use of military power

sees the world divided between good and evil, friends and enemies

hard power (coercion and force)

Слайд 22Explaining the EU today

The EU today sits somewhere along the

continuum between an international organization and a state, and has

been moving away from the former and closer to the latter. But just where it sits on that continuum has been a matter for intense debate:It has many of the typical features of an international organization, in that membership of the EU is voluntary, the balance of sovereignty lies with the member states, decision making is consultative, and the procedures used to direct the work of the EU are based on consent rather than compulsion.

It also has many of the typical features of a state, in that it has internationally recognized borders, there is a European system of law to which all member states are subject, it has authority that impacts the lives of Europeans, the balance of responsibility and power in many policy areas has shifted to the European level, and in some areas - such as trade - the EU functions as a unit, has become all but sovereign, and is recognized by other states as a legitimate player.

Слайд 23The Evolution of the EU Phases

1. First steps towards integration

(1945-1958)

2. The European Economic Community (1958-1986)

3. Economic and social integration

(1979-1992)4. From Community to Union (1992-2009)

5. Further challenges, further changes (2009- )

Слайд 25The priority for European leaders after the Second World War

was to create the conditions that would prevent Europeans from

ever going to war with each other again. For many, the major threats to peace and security were nationalism and the nation state, both of which had been discredited by the war. For most, Germany was the core problem - peace was impossible, it was argued, unless Germany could be contained and its power diverted to constructive rather than destructive ends. It had to be allowed to rebuild its economic base and its political system, but in ways that would not threaten European security.Meanwhile, tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union led Europeans to worry that they were becoming pawns in the cold war. There was clearly a need to protect Western Europe from the Soviet threat, but there were also doubts about the extent to which Europeans and Americans could find common ground, and to which Western Europe could rely on US protection. Europe might be better advised to take care of its own security, but this would require a greater sense of unity and common purpose than it had ever been able to achieve.

Слайд 26Western European governments quickly realized that changes taking place at

the global level demanded new thinking. In July 1944 ,

representatives from 44 countries - including the United States and all the allied European states - had met at Bretton Woods in New Hampshire to make plans for the postwar global economy. All agreed to an Anglo-American proposal to promote free trade, non-discrimination and stable exchange rates, and supported the view that Europe's economies should be rebuilt and placed on a more stable footing.Слайд 27It soon became clear that substantial capital investment was needed

to bolster reconstruction. The readiest source of such capital was

the United States, which saw Europe's welfare as essential to its own economic and security interests, and made a large investment in the future of Europe through the Marshall Plan.Слайд 28In June 1948 three zones of occupation were united into

a new West German state with a new currency.

In 1949

the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was created, by which the United States agreed to help its European allies 'restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area'. Canada, too, joined, along with the Benelux countries, Britain, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Norway, and Portugal.Слайд 29National pro-European groups decided to organize a conference aimed at

publicizing the cause of regional unity. The key result of

the Congress of Europe, held in The Hague in May 1948 , was the Council of Europe, founded with the signing in London in May 1949 of a statute by ten Western European states. The statute noted the need for 'closer unity between all the like-minded countries of Europe' and included among the Council's aims 'common action in economic, social, cultural, scientific, legal and administrative matters'.Although membership of the Council expanded, however, it never became more than a loose intergovernmental organization, and was not the kind of body that European federalists wanted.

Слайд 30The critical first step was taken on 9 May 1950,

at a press conference held at the French Foreign Ministry

in Paris. To the attendant journalists, French foreign minister Robert Schuman announced a plan under which Europe's national coal and steel industries would be brought together under the administration of a single joint authority.Слайд 31The European Coal and Steel Community was founded in 1952

with just six member states (France, West Germany, Italy and

the three Benelux countries), but from this modest first step a complex process of experimentation, political action, opportunism, intrigue, crisis and serendipity would eventually lead to the European Union as we know it today.The original priorities were threefold:

postwar economic construction,

the desire to prevent European nationalism leading once again to conflict,

the need for security in the face of the threats posed by the cold war.

At the core of this thinking was concern about the traditional hostility between France and Germany, and the argument that if these two could cooperate it might provide the foundations for broader European integration.

Слайд 32European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was governed by a

nominated nine-member High Authority (with Jean Monnet as its first

president), and decisions were taken by a sixmember Special Council of Ministers.A nominated 78-member Common Assembly helped Monnet allay the fears of national governments regarding the surrender of powers, and disputes between states were to be settled by a seven-member Court of Justice.

Слайд 34A new round of negotiations led to the signing in

March 1957 of the two Treaties of Rome, one creating

the European Economic Community (EEC) and the other - the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), both of which came into existence in January 1958.The EEC had a similar administrative structure to the ECSC, with a nine-member quasi-executive Commission, a Council of Ministers with powers over decision making, and a seven-member Court of Justice. A new 142-member Parliamentary Assembly was also created to cover the EEC, ECSC and Euratom; in 1962 it was renamed the European Parliament.

Слайд 35The EEC Treaty committed the Six to the creation of

a common market within 12 years by gradually removing all

restrictions on internal trade, setting a common external tariff for goods coming into the EEC, reducing barriers to the free movement of people, money, goods and services among the member states, developing common agricultural and transport policies, and creating a European Social Fund and a European Investment Bank.Action would be taken in areas where there was agreement, and disagreements could be set aside for future discussion.

The Euratom Treaty, meanwhile, was aimed at creating a common market for atomic energy, but Euratom was to remain a junior actor in the process of integration and focused primarily on research.

Слайд 36Decision making was streamlined in April 1965 with the Merger

treaty, which combined into one the separate councils of ministers

and commissions of the three communities.The decision making process was given both authority and direction by the formalization in 1975 of regular summits of EEC leaders coming together as the European Council.

The EEC was also made more democratic with the introduction in 1979 of direct elections to the European Parliament.

Слайд 37Although the 12-year deadline for the creation of a common

market was not met, internal tariffs fell quickly enough to

allow the Six to agree a common external tariff in July 1968, and to declare an industrial customs union.Integration meant the removal of the quota restrictions that member states had used to protect their domestic industries from competition from imported products. Intra-EEC trade between 1958 and 1965 grew three times faster than that with third countries, the GNP of the Six grew at an average annual rate of 5.7 per cent, per capita income and consumption grew at 4.5 per cent, and the contribution of agriculture to GNP was halved.

Слайд 38Britain was not opposed to European cooperation, but had doubts

about what the EEC was trying to achieve, and instead

championed a looser exercise in cooperation known as the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).With a goal of free trade rather than economic and political integration, EFTA was founded in January 1960 with the signing of the Stockholm Convention by Austria, Britain, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland.

EFTA helped cut tariffs, but achieved relatively little in the long term, mainly because several of its members did more trade with the EEC than with their EFTA partners.

Слайд 39The doubling of membership had several political and economic consequences:

it

increased the global influence of the EEC,

it complicated the Community's

decision making processes,it reduced the overall influence of France and Germany,

it altered the Community's relations with the United States and with developing countries,

by bringing in the poorer Mediterranean states - it altered the internal economic balance of the EEC.

Rather than enlarging any further, it was now decided to focus on deepening ties among the Twelve.

Слайд 41By 1986 the EEC had become known simply as the

European Community (EC). Its member states had a combined population

of 322 million and accounted for just over one-fifth of all world trade. The EC had its own administrative structure and an independent body of law, and its citizens had direct (but limited) representation through the European Parliament. But progress towards integration remained uneven. The customs union was in place, but completion of the common market was handicapped by barriers to the free movement of people and capital, including different national technical, health, and quality standards, and varying levels of indirect taxation. It was also clear that there could never be a true single market without a common European currency, a controversial idea because it would mean a significant loss of national sovereignty and a significant move towards political union.These issues had now begun to concern EC leaders, who responded with the two critical initiatives: the launch of the European Monetary System, and the signature of the Single European Act.

Слайд 42In 1979, a new initiative was launched in the form

of the European Monetary System (EMS). Using an Exchange Rate

Mechanism (ERM) based around an accounting tool known as the European currency unit (ecu), the EMS was designed to create a zone of monetary stability and to control fluctuations in exchange rates. The hope was that the ecu would become the normal means of settling debts among Community members, psychologically preparing them for the idea of a single currencyСлайд 43Meanwhile there was concern that progress towards the single market

was being handicapped by inflation and unemployment, and by the

temptation of member states to protect their home industries with non-tariff barriers such as subsidies. Economic competition from the United States and Japan was also growing.In response, a decision was reached at the 1983 European Council meeting in Stuttgart to refocus on the original core goal of creating a single market.

The result was the signature in Luxembourg in February 1986 of the Single European Act (SEA), which came into force in July 1987.

Слайд 45It created the single biggest market and trading power in

the world. Many internal passport and customs controls were eased

or lifted, banks and companies could do business throughout the Community, there was little to prevent EC residents living, working, opening bank accounts and drawing their pensions anywhere in the Community, EC competition policy was given new prominence, and monopolies on everything from electricity supply to telecommunications were broken down.It gave Community institutions responsibility over new policy areas that had not been covered in the Treaty of Rome, such as the environment, research and development, and regional policy.

Слайд 46It gave new powers to the European Court of Justice,

and created a Court of First Instance to hear certain

kinds of cases and ease the workload of the Court of Justice.It gave legal status to meetings of heads of government under the European Council, and gave new powers to the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament.

It gave legal status to European Political Cooperation (foreign policy coordination) so that member states could work towards a European foreign policy and work more closely on defence and security issues.

It made economic and monetary union an EC objective and promoted 'cohesion', meaning the reduction of the gap between the richer and poorer parts of the EC.

Слайд 47Despite the signing of the SEA, progress on opening up

borders was variable, and there was no common European policy

on immigration, visas, and asylum. Impatient to move ahead, the governments of France, Germany, and the Benelux states in 1985 signed the Schengen Agreement, under which all border controls were to be removed among signatory countries.All 27 EU member states have now signed the agreement, along with Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, but not all have introduced truly passport-free travel (Britain, Ireland have stayed out of most elements of Schengen), and the terms of the agreement allow the signatories to implement special controls at any time.

Слайд 48New attention was drawn to social policy in 1989 with

agreement of the Charter of Fundamental Social Rights of Workers

(the Social Charter), which promoted the free movement of workers, fair pay, better living and working conditions, freedom of association, and protection of children and adolescents.Social issues are now one of the core policy areas for the European Union, with many of the actions taken by the governments of the member states driven by the requirements of EU law. The latter has addressed issues as varied as health and safety at work, parental leave from work, public health, and programmes to help the disabled and the elderly.

Слайд 50The outcome of this phase was the Treaty on European

Union, agreed at the European Council summit in Maastricht in

December 1991 and signed by the foreign and economics ministers of the Community in February 1992.The draft treaty had included the goal of federal union, but Britain had balked at this so the wording was changed to 'an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe, in which decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen'.

Слайд 51Like the Single European Act before it, the Treaty on

European Union - usually known as the Maastricht treaty -

made some significant changes to the contract among the member states of the EU:Слайд 52Reflecting the lengths to which the member states will occasionally

go to reach compromises, a peculiar arrangement was agreed by

which – instead of new powers being given to the European Community - three 'pillars‘ were created, and the whole structure was given the new label 'European Union'. The first pillar consisted of the three pre-existing communities (economic, coal and steel, and atomic energy), and the second and third pillars consisted of areas in which there was to be more formal intergovernmental cooperation: a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), and justice and home affairs. Final responsibility for the CFSP remained with the individual governments rather than being handed over to the EU.The pillar arrangement is a diplomatic sideshow that is marginal to an understanding of the EU today.

Слайд 53The EU according to

the Maastricht Treaty

The EU

The three

pre-existing

communities

(economic,

coal and

steel,

and atomic energy)

Common Foreign

and Security

Policy (CFSP)

Justice and

Home Affairs

Policy

The First Pillar

The

Second PillarThe Third Pillar

Слайд 54A timetable was agreed for the creation of a single

European currency by January 1999.

EU responsibility was extended into new

policy areas such as consumer protection, public health policy, transport, education, and (except in Britain) social policy.There was to be greater intergovernmental cooperation on immigration and asylum, a European police intelligence agency (Europol) was to be created to combat organized crime and drug trafficking, a new Committee of the Regions was set up, and regional funds for poorer EU states were increased.

Слайд 55New rights were provided for European citizens and an ambiguous

European Union 'citizenship' was created which meant, for example, the

right of citizens to live wherever they liked in the EU, and to stand or vote in local and European elections.New powers were given to the European Parliament, including a 'codecision procedure' under which certain kinds of legislation are subject to a third reading in the European Parliament before they can be adopted by the Council of Ministers.

Слайд 56Meanwhile enlargement was still on the agenda, the end of

the cold war leading to a new focus on expansion

to Eastern Europe. At its June 1993 meeting in Copenhagen, the European Council agreed a formal set of requirements for membership of the EU. Known as the Copenhagen conditions, they require that an applicant state must(a) be democratic, with respect for human rights and the rule of law,

(b) have a functioning free market economy and the capacity to cope with the competitive pressures of capitalism, and

(c) be able to take on the obligations of the acquis communautaire (the body of laws and policies already adopted by the EU).

Deciding whether applicants meet these criteria has proved difficult.

Слайд 57Partly in preparation for anticipated eastern enlargement, but also to

account for the progress of European integration and perhaps move

the EU closer to political union, two new treaties were signed in 1997 - 2000.The first was the Treaty of Amsterdam, which was signed in October 1997 and came into force in May 1999.

It fell far short of achieving political union to accompany the economic and monetary union promoted by the SEA and Maastricht, and the 15 leaders were unable to agree anything more than modest changes to the structure of EU institutions in preparation for enlargement. Policies on asylum, visas, external border controls, immigration, employment, social policy, health protection, consumer protection, and the environment were developed, cooperation between national police forces (and the work of Europol) was strengthened, and improvements were made to the arrangements for EU foreign policy. There was also agreement on the goal of a single European currency, and on the principle of eastern enlargement.

Слайд 58The key goal of the Treaty of Nice - agreed

in December 2000 and signed in February 2001 - was

to make the institutional changes needed to prepare for eastward enlargement, and to make the EU more democratic and transparent.Слайд 60At the Laeken European Council in December 2001 it was

decided to establish a convention to debate the future of

Europe, and to draw up a treaty containing a constitution designed to simplify and replace all the other treaties, to decide how to divide powers between the EU and the member states, to make the EU more democratic and efficient, to determine the role of national parliaments within the EU, and to pave the way for more enlargement.The Convention on the Future of the European Union met between February 2002 and July 2003 considered numerous proposals, including an elected president of the European Council, a foreign minister for the EU, a limit on the membership of the European Commission, a common EU foreign and security policy, and a legal personality for the EU, whose laws would cancel out those of national parliaments in areas where the EU had been given competence. It took two European Council meetings (December 2003 and June 2004) to reach agreement on the draft treaty, which had then to be put to public referendums or government votes in every EU member state.

Слайд 61The popular expectation being that the treaty was unlikely to

survive a referendum in Eurosceptical Britain. But it was left

to the French and the Dutch - both founding members of the European Union - to stop the process in its tracks, with negative votes in national referendums in May and June 2005 respectively.Слайд 62The negative votes led to widespread predictions of institutional collapse

and loss of strategic direction, but the EU survived and

continued to function, while worried discussions were held about the next step. At the European Council in June 2007 it was decided to save as many elements as possible of the constitution, and to reformulate them into a new treaty designed mainly to adjust the institutional structure of the EU to account for enlargement.A new treaty of Lisbon had been agreed, signed and ratified.

Слайд 63The Treaty of Lisbon entered into force on 1 December

2009.

Here is a brief summary of the main changes:

A single

legal personalityA President of the European Council

A High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy

A new European External Action Service

Double majority (qualified majority) in the Council

Codecision extended

Setting the number of MEPs

A new role for national parliaments

Citizens' right of initiative

The Charter of Fundamental Rights

Слайд 64The History of the European Union (European Comission Idea)

1945

– 1959 A peaceful Europe – the beginnings of cooperation

1960

– 1969 The ‘Swinging Sixties’ – a period of economic growth1970 – 1979 A growing Community – the first Enlargement

1980 – 1989 The changing face of Europe - the fall of the Berlin Wall

1990 – 1999 A Europe without frontiers

2000 – today A decade of further expansion