Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

European Integration History: Phases, Results and Achievements. Political

Содержание

- 1. European Integration History: Phases, Results and Achievements. Political

- 2. 2.2. European Union Foreign, Security and Defence Policies

- 3. The EU and the WorldBuilding a European

- 4. Polls find that 75 per cent of

- 5. The European Defence Community (EDC) was proposed

- 6. European Political Cooperation (EPC) was launched at

- 7. The European Council was launched in 1974

- 8. EPC was given formal recognition with the

- 9. The divisions over the war - coupled

- 10. The EU according to the Maastricht Treaty

- 11. CFSP brought about a steady convergence of

- 12. Some of the structural weaknesses in the

- 13. A Policy Planning and Early Warning Unit

- 14. Changes introduced by the Lisbon Treaty in

- 15. In June 1992, EU foreign and defence

- 16. In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam resulted

- 17. An attempt had already been made to

- 18. In 1999 the European Security and Defence

- 19. The plan was to have it ready

- 20. In December 2003, the European Council adopted

- 21. The EU has no standing army. Instead,

- 22. Following the entry into force of the

- 23. The High Representative is assisted by the

- 24. 2.3. European Union Justice and Home Affairs

- 25. To enjoy freedom fully, people must be

- 26. JusticeYou can cross most of the EU

- 27. Guaranteeing fundamental rightsThe EU is based on

- 28. Cooperation between judicial authorities EU authorities work

- 29. Home AffairsManaging asylum and immigration:Common minimum standards

- 30. Home AffairsAddressing internal security challenges:The EU's common

- 31. Скачать презентанцию

2.2. European Union Foreign, Security and Defence Policies

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 1European Integration History: Phases, Results and Achievements. Political Challenges of the EU

Слайд 3The EU and the World

Building a European foreign policy

Common Foreign

and Security Policy (CFSP)

Towards a European defence policy

Слайд 4Polls find that 75 per cent of Europeans support a

common defence and security policy, 68 per cent support a

common foreign policy, and 49 per cent believe that decisions on defence policy should be taken by the EU (compared to 21 per cent by national governments and 17 per cent by NATO).They also feel (by large margins) that the EU can play a more positive role than the United States in promoting international peace, encouraging environmental protection, pursuing the war on terrorism, and fighting poverty.

(Eurobarometer 66, December 2006)

Слайд 5The European Defence Community (EDC) was proposed in 1950, was

pursued most actively by the French, and was to have

been built on the foundations of a common European army and a European minister of defence. However, Britain was opposed to the idea, preferring to pursue the goals of the Treaty of Brussels and to bring Italy and West Germany into the fold. All prospects of an EDC finally died in 1 9 5 4 when the French National Assembly turned it down.Слайд 6European Political Cooperation (EPC) was launched at the summit of

Community leaders in Hague in 1969.

It was a

process by which the six foreign ministers would meet to discuss and coordinate foreign policy positions. EPC was not incorporated into the founding treaties, it remained a loose and voluntary arrangement outside the Community, no laws were adopted on foreign policy, each of the member states could still act independently, and most of the key decisions on foreign policy had to be unanimous. Слайд 7The European Council was launched in 1974 in part to

bring leaders of the member states together to coordinate policies.

EPC

was strictly intergovernmental, and was overseen by the foreign ministers meeting as the Council of Ministers, with overall leadership coming from the European Council. Regular meetings of senior officials from all the foreign ministries provided continuity, and a small secretariat was set up in Brussels to help the country holding the presidency of the Council of Ministers, which provided most of the momentum. Слайд 8EPC was given formal recognition with the Single European Act,

which confirmed that the member states would 'endeavour jointly to

formulate and implement a European foreign policy'.But then came the Gulf War of 1990 - 91 , which found the Community both divided and unprepared.

Слайд 9The divisions over the war - coupled with the dramatic

changes then taking place in Eastern Europe and the former

USSR - emphasized the need for Europe to address its foreign policy more forcefully, and political pressure grew for a review of EPC.The result was its replacement under Maastricht by the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP).

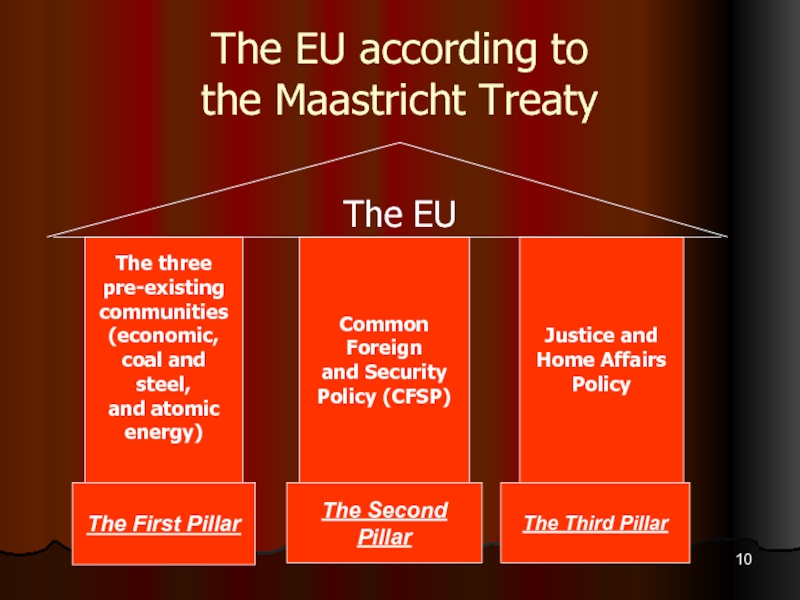

Слайд 10The EU according to

the Maastricht Treaty

The EU

The three

pre-existing

communities

(economic,

coal and

steel,

and atomic energy)

Common Foreign

and Security

Policy (CFSP)

Justice and

Home Affairs

Policy

The First Pillar

The

Second PillarThe Third Pillar

Слайд 11CFSP brought about a steady convergence of positions among the

member states on key international issues. Their UN ambassadors met

frequently to coordinate policy, the EU agreed several 'common strategies', such as those on Russia and the Ukraine, 'joint actions', such as transporting humanitarian aid to Bosnia and sending observers to elections in Russia and South Africa, and 'common positions' on EU relations with other countries, including the Balkans, the Middle East, Myanmar, and Zimbabwe.Слайд 12Some of the structural weaknesses in the CFSP were addressed

by the Treaty of Amsterdam: as well as opening up

the possibility of limited majority voting on foreign policy issues.Слайд 13A Policy Planning and Early Warning Unit was also created

in Brussels to help the EU anticipate foreign crises, and

the old habit of having four different regional external affairs portfolios in the European Commission ended with the creation of a single foreign policy post and the appointment of a High Representative on foreign policy; the first office-holder was Javier Solana, former secretary-general of NATOСлайд 14Changes introduced by the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 make it

easier for the EU to be more active and coherent

in the CFSP.These changes include the appointment of an EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who coordinates between EU countries to shape and implement foreign policy. The High Representative is assisted by civilian and military staff, the European External Action Service.

Слайд 15In June 1992, EU foreign and defence inisters meeting at

Petersberg, near Bonn, issued a declaration in which they agreed

that military units from member states could be used to promote the 'Petersberg talks':humanitarian,

rescue,

peacekeeping,

other crisis management jobs (including peacemaking).

Слайд 16In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam resulted in the incorporation

of the Petersberg tasks into the EU treaties, and newly-minted

British prime minister Tony Blair signalled his willingness to see Britain play a more central role in EU defence matters.Слайд 17An attempt had already been made to build a common

European military outside EU and NATO structures with the founding

in May 1992 of Eurocorps, set up by France and Germany to replace an experimental Franco-German brigade set up in 1990. Headquartered in Strasbourg, the 60,000-member Eurocorps became operational in November 1995, has been joined by contingents from Belgium, Luxembourg, and Spain, and has sent missions to Bosnia (1998), Kosovo (2000), and Afghanistan (2004).Слайд 18In 1999 the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) was

launched.

An integral part of the CFSP, this was to

consist of two key components:the Petersberg tasks,

a 60,000-member Rapid Reaction Force (RRF) that could be deployed at 60 days' notice and sustained for at least one year, and could carry out these tasks.

The Force - championed mainly by Britain and France - was not intended to be a standing army, was designed to complement rather than compete with NATO, and could only act when NATO had decided not to be involved in a crisis.

Слайд 19The plan was to have it ready by the end

of 2003, but it proved more of a challenge than

expected, and by 2004 the EU was talking of the more modest goal of creating 'battle groups' that could be deployed more quickly and for shorter periods than the RRF. The groups would consist of 1,500 troops each that could be committed within 15 days, and could be sustainable for between 30 and 120 days.Слайд 20In December 2003, the European Council adopted the European Security

Strategy, the first ever declaration by EU member states of

their strategic goals.The Strategy declared that the EU was 'inevitably a global player', and 'should be ready to share in the responsibility for global security'. It listed the key threats facing the EU as terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, regional conflicts, failing states, and organized crime.

Слайд 21The EU has no standing army. Instead, under its Common

Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), it relies on ad hoc

forces contributed by EU countries for:joint disarmament operations

humanitarian and rescue tasks

military advice and assistance

conflict prevention and peace-keeping

tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peace-making and post-conflict stabilisation.

All these tasks may contribute to the fight against terrorism, including by supporting third countries in combating terrorism in their territories.

Слайд 22Following the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon,

the European Council appointed Catherine Ashton High Representative of the

Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.She chairs the Foreign Affairs Council and conducts the Common Foreign and Security Policy. Drawing on her role as Vice-President of the European Commission, she ensures the consistency and coordination of the European Union's external action.

Слайд 23The High Representative is assisted by the European External Action

Service (EEAS). EEAS staff come from the European Commission, the

General Secretariat of the Council and the Diplomatic Services of EU Member States.Слайд 242.3. European Union Justice and Home Affairs Policy.

Supporting people rights,

defending people interests

Justice

Guaranteeing fundamental rights

Home Affairs:

managing asylum and immigration

addressing

internal security challengesСлайд 25To enjoy freedom fully, people must be able to live

their lives and go about their business in security and

safety – safe from international crime and terrorism.They should also have access to the local justice system and be able to trust that their fundamental rights will be respected wherever they are in the EU.

In addition, immigration from non-EU countries needs to be managed in a fair and sustainable way.

Слайд 26Justice

You can cross most of the EU without a passport

or border checks.

In a Europe of open borders, more and

more people live, work and do business in other EU countries. The EU wants to make life easier for them by building an EU-wide area of justice. The aim is to offer practical solutions to cross-border problems, so that citizens feel at ease when moving around the EU and businesses can make full use of the Single Market.Слайд 27Guaranteeing fundamental rights

The EU is based on respect for human

rights, democratic institutions and the rule of law. Its Charter

of Fundamental Rights sets out all the personal, civil, political, economic and social rights EU citizens enjoy. The EU's Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) helps policymakers to pass new laws and works to raise public awareness of fundamental rights.Слайд 28Cooperation between judicial authorities

EU authorities work together to beat

cross-border crime.

Cooperation has intensified between national judicial authorities to ensure

that legal decisions taken in one member country are recognised and implemented in any other. To help in the fight against serious crimes such as corruption, drug trafficking and terrorism, the EU has established the European Judicial Network.

The European arrest warrant has replaced lengthy extradition procedures, so that suspected or convicted criminals who have fled abroad can be swiftly returned to the country where they were tried, or are due to be tried.

Слайд 29Home Affairs

Managing asylum and immigration:

Common minimum standards and procedures for

asylum seekers are intended to guarantee a high level of

protection for those who need it, while ensuring that national asylum systems cannot be abused.EU leaders are also developing a common, balanced and comprehensive EU immigration policy in order to seize the opportunities that legal immigration may bring to the European economies and societies, while tackling the challenges of irregular immigration.

Furthermore, effective controls at all points of entry into the EU are a precondition for the freedom of movement of people in the Union. EU countries are working together to improve security through better external border controls, while making it easier for those with a right to enter the EU to do so. Operational cooperation between EU countries is managed by the EU external borders agency FRONTEX.

Слайд 30Home Affairs

Addressing internal security challenges:

The EU's common internal security strategy

sets out to improve internal security through cooperation on law

enforcement, border management, civil protection and disaster management.The strategy includes legislation and practical ways to stop organised criminals – drug barons, human traffickers, money launderers, terrorists – from exploiting the freedoms the EU brings and to improve cooperation between national police forces, especially within the framework of the European Police Office (Europol).