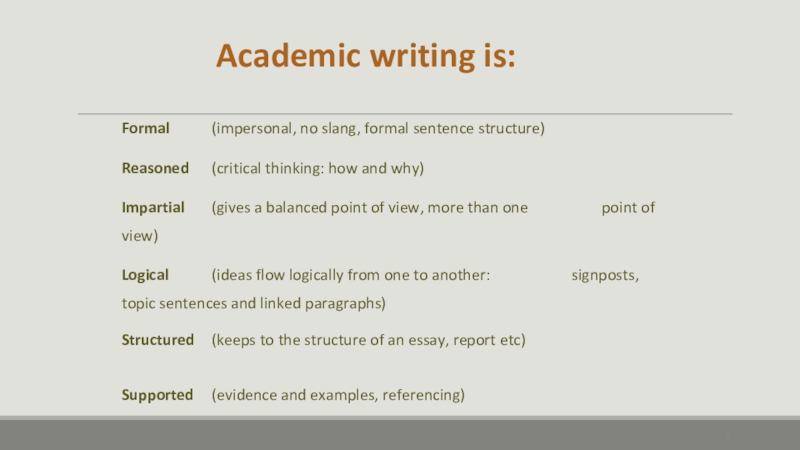

Слайд 2Academic writing is:

Formal (impersonal, no slang, formal sentence structure)

Reasoned (critical

thinking: how and why)

Impartial (gives a balanced point of view,

more than one point of view)

Logical (ideas flow logically from one to another: signposts, topic sentences and linked paragraphs)

Structured (keeps to the structure of an essay, report etc)

Supported (evidence and examples, referencing)

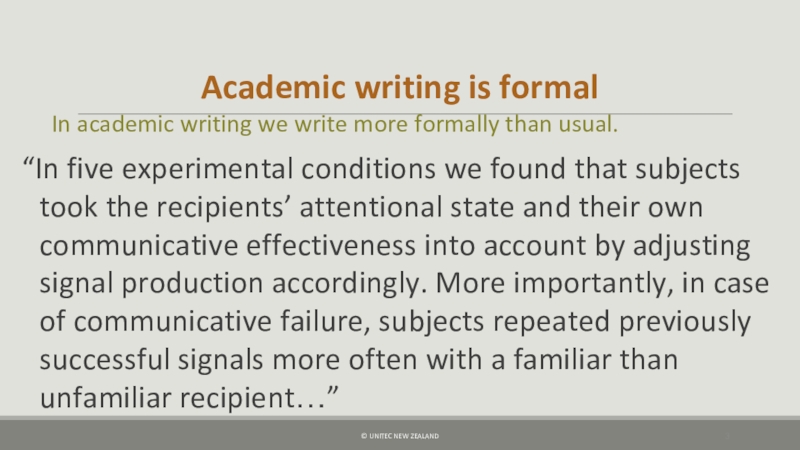

Слайд 3Academic writing is formal

In academic writing we write more formally

than usual.

“In five experimental conditions we found that subjects took

the recipients’ attentional state and their own communicative effectiveness into account by adjusting signal production accordingly. More importantly, in case of communicative failure, subjects repeated previously successful signals more often with a familiar than unfamiliar recipient…”

© Unitec New Zealand

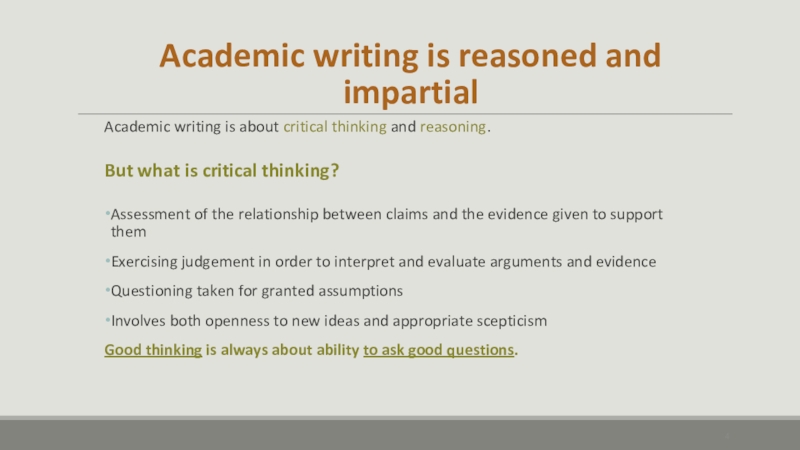

Слайд 4Academic writing is reasoned and impartial

Academic writing is about critical

thinking and reasoning.

But what is critical thinking?

Assessment of the

relationship between claims and the evidence given to support them

Exercising judgement in order to interpret and evaluate arguments and evidence

Questioning taken for granted assumptions

Involves both openness to new ideas and appropriate scepticism

Good thinking is always about ability to ask good questions.

Слайд 5Academic writing is structured

Article structure

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

Слайд 6Academic writing is logical

To create a piece of writing that

is logical requires planning.

A good way to plan an

assignment is to put down your ideas in bullet points using one page. You can also create a ‘mindmap’ for your ideas or list a series of questions.

Another key aspect in creating a logical piece of writing involves writing in paragraphs.

A report or essay is made up of a series of related paragraphs.

Paragraphs organise meaning. They help your readers to think clearly about what you have written.

Слайд 7An Academic Paragraph

a paragraph introduces and develops one main idea

the main idea is introduced through a topic sentence, which

is usually the first sentence

all sentences in the paragraph need to relate to the main idea in a logical way

paragraphs are linked together and flow logically on from each other

in-text references need to be included in the paragraph if supporting ideas come from other sources.

Слайд 8Using words

Use the minimum number of words!

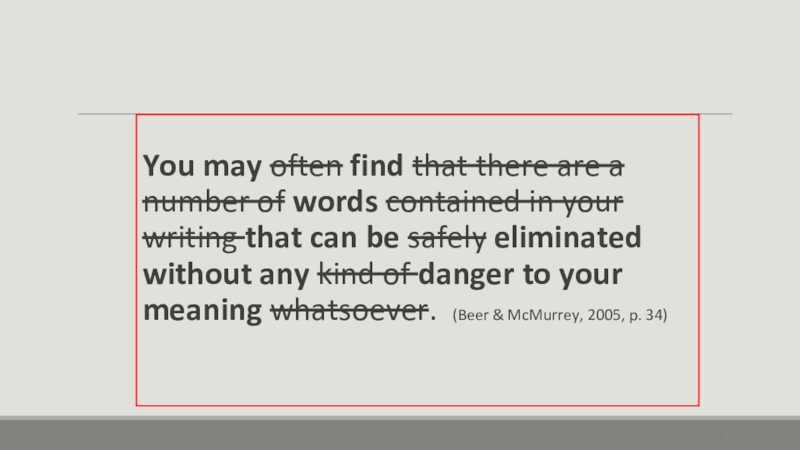

You may often

find that there are a number of words contained in

your writing that can be safely eliminated without any kind of danger to your meaning whatsoever. X

Слайд 9

You may often find that there are a number of

words contained in your writing that can be safely eliminated

without any kind of danger to your meaning whatsoever. (Beer & McMurrey, 2005, p. 34)

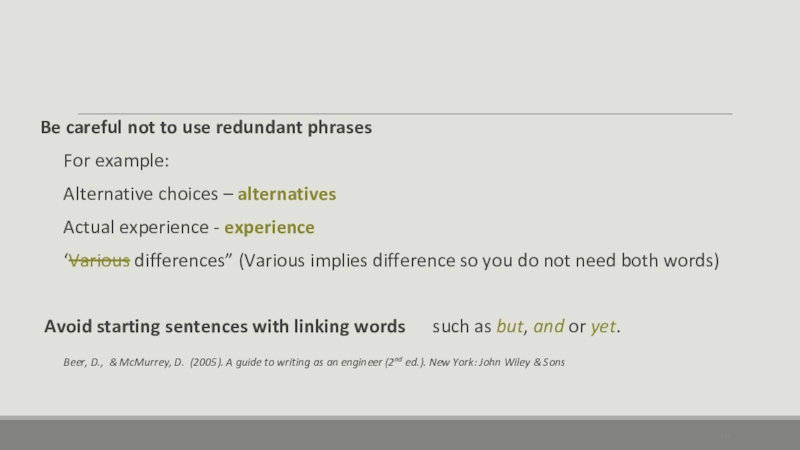

Слайд 10Be careful not to use redundant phrases

For example:

Alternative choices

– alternatives

Actual experience - experience

‘Various differences” (Various implies difference so

you do not need both words)

Avoid starting sentences with linking words such as but, and or yet.

Beer, D., & McMurrey, D. (2005). A guide to writing as an engineer (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons

Слайд 11Grammar in Academic English

Usage of tenses

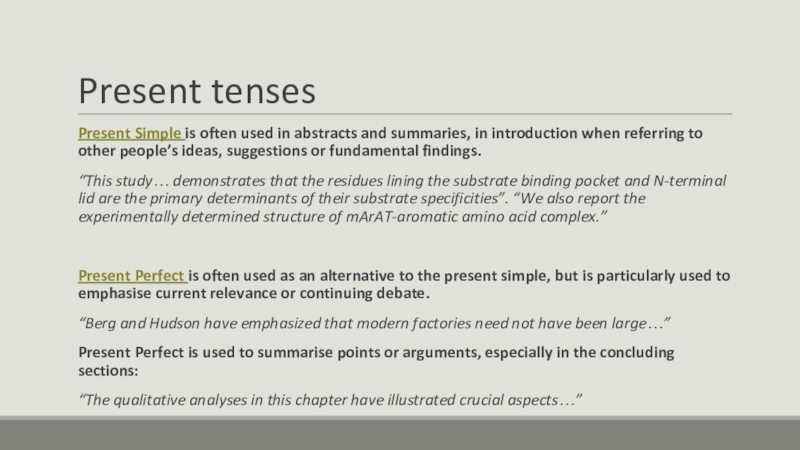

Слайд 12Present tenses

Present Simple is often used in abstracts and summaries,

in introduction when referring to other people’s ideas, suggestions or

fundamental findings.

“This study… demonstrates that the residues lining the substrate binding pocket and N-terminal lid are the primary determinants of their substrate specificities”. “We also report the experimentally determined structure of mArAT-aromatic amino acid complex.”

Present Perfect is often used as an alternative to the present simple, but is particularly used to emphasise current relevance or continuing debate.

“Berg and Hudson have emphasized that modern factories need not have been large…”

Present Perfect is used to summarise points or arguments, especially in the concluding sections:

“The qualitative analyses in this chapter have illustrated crucial aspects…”

Слайд 13Past Simple

Past Simple is used to refer to procedures used

in individual studies:

“Borgen et al statistically modelled the magnitude of

such temperature…”

“Our functional assays clearly showed the inability of mArAT to catalyze Hsp as substrate, but it exhibited broad specificity for aromatic amino acids.”

“To explore the conservation of active site residues of Iβ aminotransferases across species, we performed a structure and sequence based alignment of mArAT and mHspAT”

Слайд 14Will / shall

In academic language will and shall may be

used to refer to things which are to be found

later in the text or to predictions which the authors make. Both simple and progressive forms are used. Sometimes Future perfect can be used as well.

“The ‘rare resource’ hypothesis predicts that two monkeys that are both holding anointing resources will not form anointing dyads, whilst the ‘mutual application’ hypothesis predicts that monkeys holding anointing resources will continue to seek out other monkeys that hold resources, and that social anointing actions will target parts of the body that are inaccessible to a monkey rubbing individually.”

“After organisational-transformations the “right” environment will likely have changed, but the right internal state remains the same.”

Слайд 15Contractions

Contracted verb forms are generally avoided in academic writing.

“In

contrast, capuchin monkeys in other studies 34,35, baboons, Papio papio

36, tonkean and rhesus macaques, Macaca tonkeana & M. mulatta 37, rooks, Corvus frugilegus5, and African grey parrots, Psittacus erithacus 38, did not pass the delay and/ or solitary control conditions, suggesting that they do not pay attention to the other’s role or even lack an understanding of the need of a partner.”

Слайд 16Active and Passive voice

Passive voice is common in academic writing

since it is often necessary to shift the focus from

human agency to the actions, processes and events described.

“Cooperative hunting has been described in social carnivores7–10, chimpanzees…“

“most emphasis has been put on whether animals understand the need and role of the partner in cooperation.”

“In experiment 1, seven ravens were confronted with the string pulling set-up in a group setting”

To signpost the section dealing with personal stance and evaluation, the author shifts to active voice:

“We investigated the cooperative problem solving abilities of ravens by using a set-up comparable to most other studies based on the loose string paradigm.”

Слайд 17Active and Passive voice

Active voice is also frequently used with

impersonal subjects, as well as to describe activities etc. of

the objects studied.

“In a group of captive Sapajus sp. the frequency of aggression increased, and durations of affiliative behaviours decreased…“

„individuals form multiple highly differentiated affiliative and agonistic relationships with others”

“The ravens cooperated successfully in 397 out of 600 trials (66.17%).”

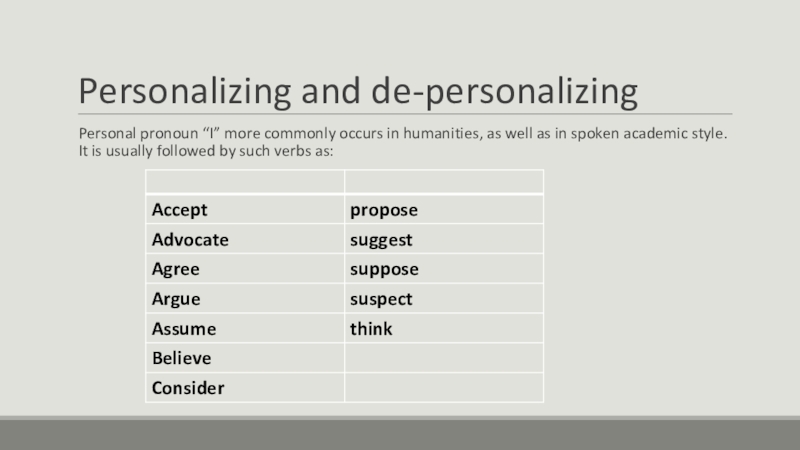

Слайд 18Personalizing and de-personalizing

Personal pronoun “I” more commonly occurs in humanities,

as well as in spoken academic style. It is usually

followed by such verbs as:

Слайд 19Personalizing and de-personalizing

“We” is typically used to refer to more

than one author of an academic paper:

“We investigated the cooperative

problem solving abilities of ravens”

Also, “we” can be used by a single author as an inclusive strategy, referring to the author and reader together, making him a part of the team:

“We know the molecular biology of this virus in very great detail”

“You” and “one” can both be used to refer to people in general, and to academic community of writer / speaker and readers / listeners. “You” is less formal than one.

“It is possible that the more words you already know, the easier it is to aсquire the meaning of new words”

“One” is less frequent than you, particularly, in spoken academic language.

Слайд 20Modality: hedging and boosting

Academic texts are often characterized by a

desire to avoid making claims and statements that are too

direct and assertive. Therefore, hedging (making a proposition less assertive) is very important in academic styles.

“The anger experience may culminate in a variety of behavioral reactions…”

Sometimes, however, it is necessary to assert a claim or viewpoint quite directly and confidently (boosting).

“We must remember, however, that migrants may not need information about more than one destination”

Слайд 21Hedging: the use of modal verbs

Can, could, might and may

Academic

English often needs to state possibilities rather than facts, and

academics frequently hypothesise and draw tentative conclusions.

Can is often used to make fairly confident but not absolute assertions:

“Genetic mutations, infection by parasites or symbionts, and other events can transform the way that an organism’s internal state changes in response to a given environment.”

Слайд 22Could and Might

Could and might are used for more tentative

assertions:

“In some cases, the disadvantageous effects of these events could

be reduced or neutralized”.

“An argument is then made as to why we might expect interoceptive behaviour to be more robust to organisational-transformations than exteroceptive behaviour.”

Слайд 23May

May describes things which are likely to occur or which

normally do occur. In this usage it is a formal

equivalent of can:

„Increased coverage on the upper back may result from self-directed rubbing a

against other anointing individuals that may be a secondary source of material”.

May is also widely used in a more general way in academic texts to make a proposition more tentative. May is less tentative than could or might:

“The social anointing behaviours in capuchin monkeys may have lead to the formulation of the social bonding hypotheses for the function of anointing in the species.”

“They may well be explained in terms of innate behaviours”.

Слайд 24Would

“Would” is frequently used to hedge assertions which may be

challenged when it precedes such verbs as “advocate”, “argue”, “assume”,

“claim”, “expect”, “propose”, “suggest”.

„Since the behaviour must be costly, we would expect it to provide significant benefits to the subjects.”

“This would suggest that birds that did not receive a reward in the previous successful cooperation trial, are less motivated to cooperate again.”

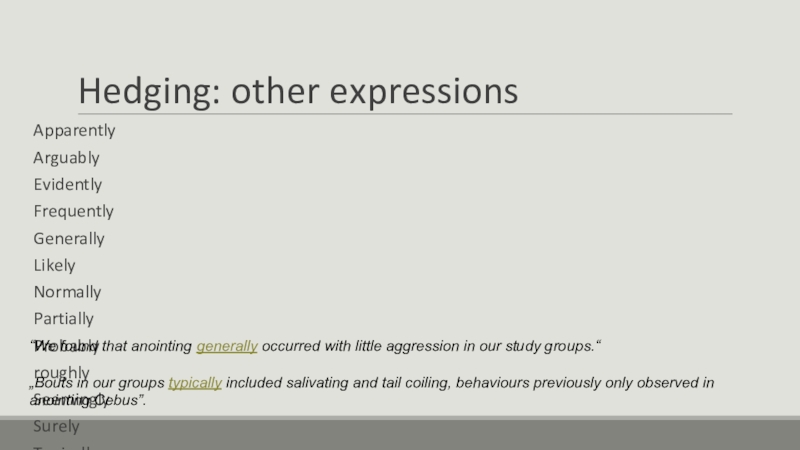

Слайд 25Hedging: other expressions

Apparently

Arguably

Evidently

Frequently

Generally

Likely

Normally

Partially

Probably

roughly

Seemingly

Surely

Typically

usually

“We found that anointing generally occurred with little

aggression in our study groups.“

„Bouts in our groups typically included

salivating and tail coiling, behaviours previously only observed in anointing Cebus”.

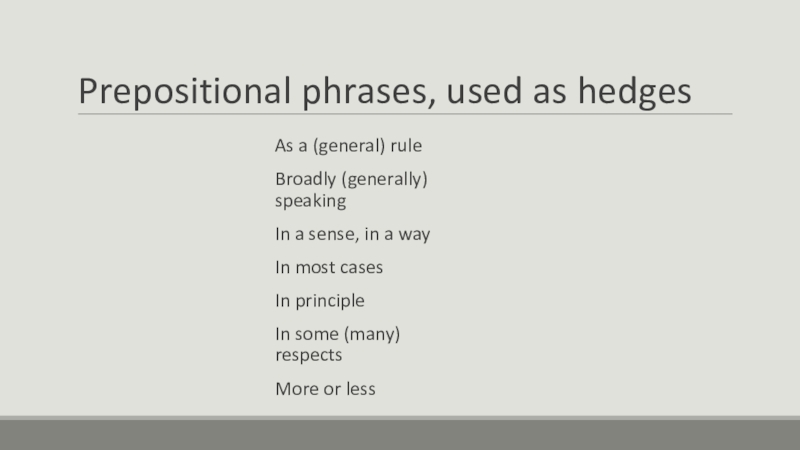

Слайд 26Prepositional phrases, used as hedges

As a (general) rule

Broadly (generally) speaking

In

a sense, in a way

In most cases

In principle

In some (many)

respects

More or less

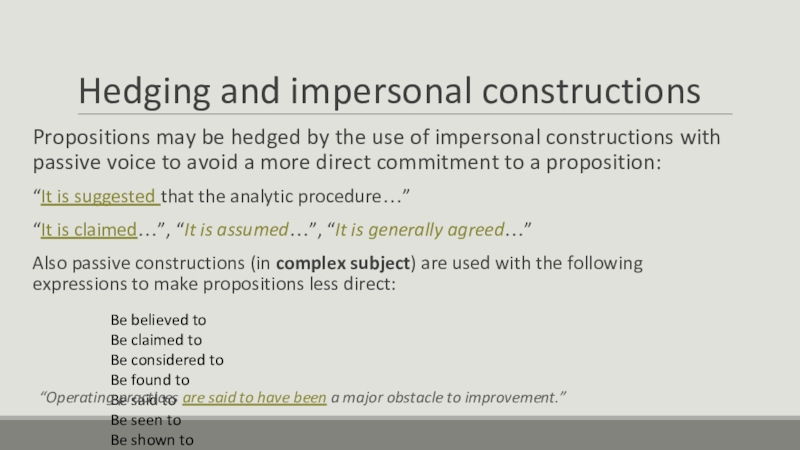

Слайд 27Hedging and impersonal constructions

Propositions may be hedged by the use

of impersonal constructions with passive voice to avoid a more

direct commitment to a proposition:

“It is suggested that the analytic procedure…”

“It is claimed…”, “It is assumed…”, “It is generally agreed…”

Also passive constructions (in complex subject) are used with the following expressions to make propositions less direct:

Be believed to

Be claimed to

Be considered to

Be found to

Be said to

Be seen to

Be shown to

Be thought to

“Operating practices are said to have been a major obstacle to improvement.”

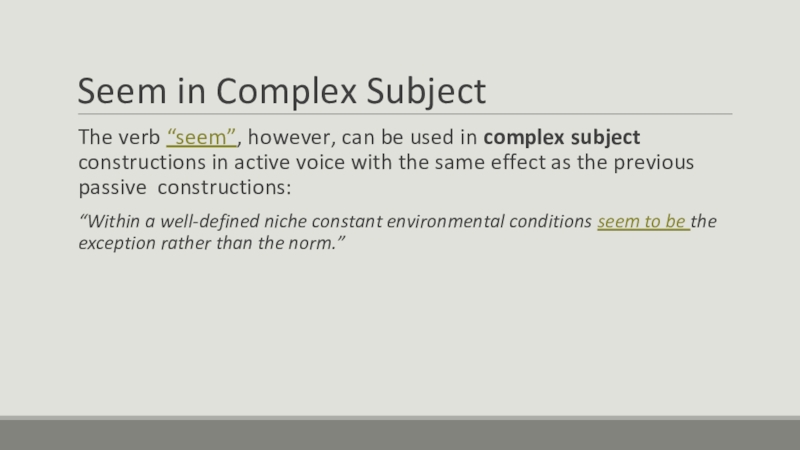

Слайд 28Seem in Complex Subject

The verb “seem”, however, can be used

in complex subject constructions in active voice with the same

effect as the previous passive constructions:

“Within a well-defined niche constant environmental conditions seem to be the exception rather than the norm.”

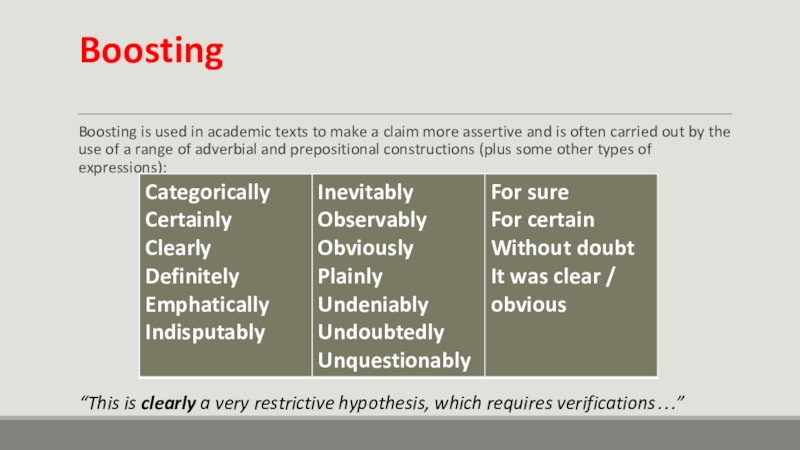

Слайд 29Boosting

Boosting is used in academic texts to make a claim

more assertive and is often carried out by the use

of a range of adverbial and prepositional constructions (plus some other types of expressions):

“This is clearly a very restrictive hypothesis, which requires verifications…”

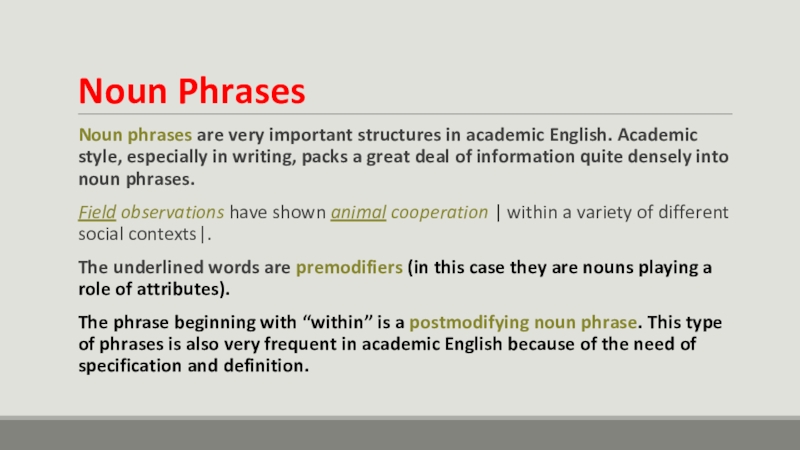

Слайд 30Noun Phrases

Noun phrases are very important structures in academic English.

Academic style, especially in writing, packs a great deal of

information quite densely into noun phrases.

Field observations have shown animal cooperation | within a variety of different social contexts|.

The underlined words are premodifiers (in this case they are nouns playing a role of attributes).

The phrase beginning with “within” is a postmodifying noun phrase. This type of phrases is also very frequent in academic English because of the need of specification and definition.

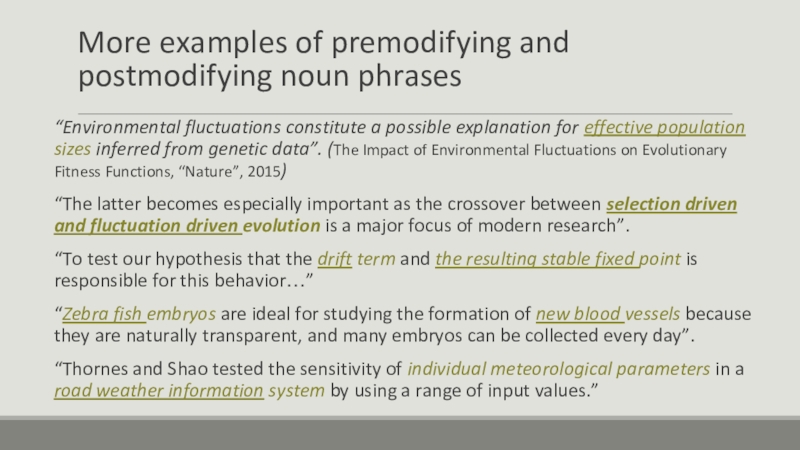

Слайд 31More examples of premodifying and postmodifying noun phrases

“Environmental fluctuations constitute

a possible explanation for effective population sizes inferred from genetic

data”. (The Impact of Environmental Fluctuations on Evolutionary Fitness Functions, “Nature”, 2015)

“The latter becomes especially important as the crossover between selection driven and fluctuation driven evolution is a major focus of modern research”.

“To test our hypothesis that the drift term and the resulting stable fixed point is responsible for this behavior…”

“Zebra fish embryos are ideal for studying the formation of new blood vessels because they are naturally transparent, and many embryos can be collected every day”.

“Thornes and Shao tested the sensitivity of individual meteorological parameters in a road weather information system by using a range of input values.”

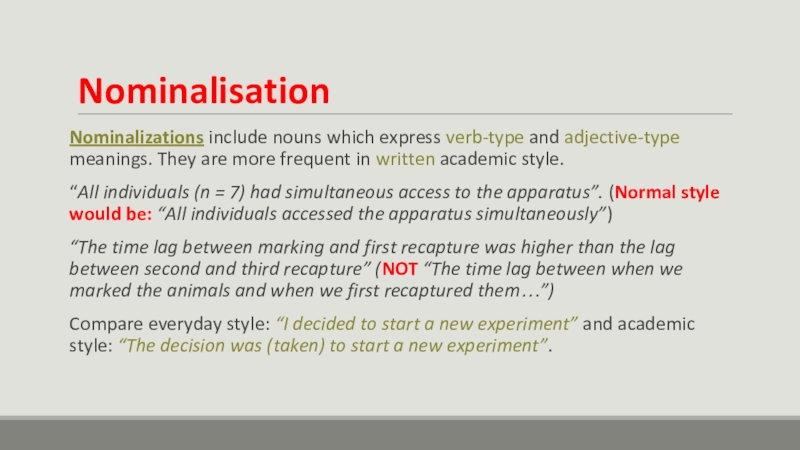

Слайд 32Nominalisation

Nominalizations include nouns which express verb-type and adjective-type meanings. They

are more frequent in written academic style.

“All individuals (n

= 7) had simultaneous access to the apparatus”. (Normal style would be: “All individuals accessed the apparatus simultaneously”)

“The time lag between marking and first recapture was higher than the lag between second and third recapture” (NOT “The time lag between when we marked the animals and when we first recaptured them…”)

Compare everyday style: “I decided to start a new experiment” and academic style: “The decision was (taken) to start a new experiment”.

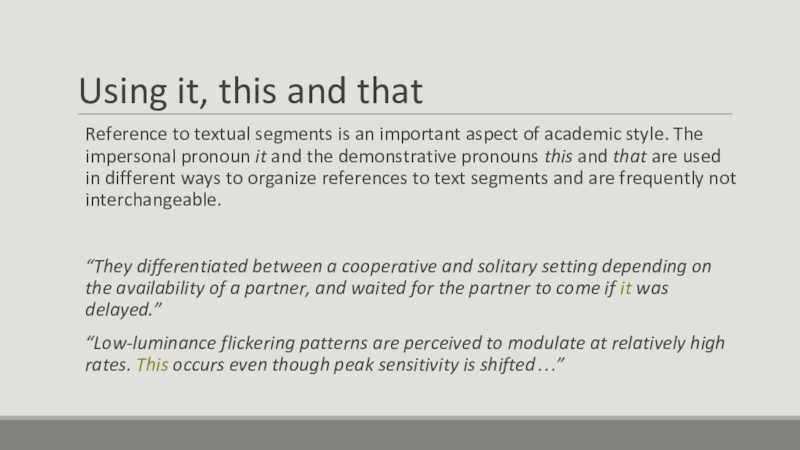

Слайд 33Using it, this and that

Reference to textual segments is an

important aspect of academic style. The impersonal pronoun it and

the demonstrative pronouns this and that are used in different ways to organize references to text segments and are frequently not interchangeable.

“They differentiated between a cooperative and solitary setting depending on the availability of a partner, and waited for the partner to come if it was delayed.”

“Low-luminance flickering patterns are perceived to modulate at relatively high rates. This occurs even though peak sensitivity is shifted…”

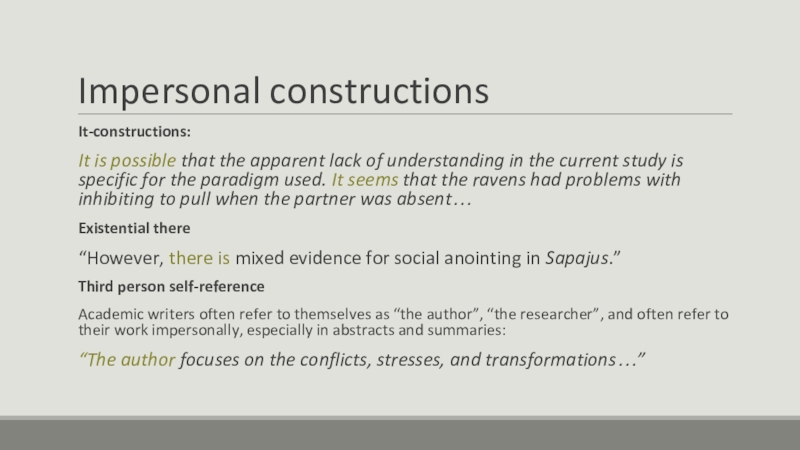

Слайд 34Impersonal constructions

It-constructions:

It is possible that the apparent lack of understanding

in the current study is specific for the paradigm used.

It seems that the ravens had problems with inhibiting to pull when the partner was absent…

Existential there

“However, there is mixed evidence for social anointing in Sapajus.”

Third person self-reference

Academic writers often refer to themselves as “the author”, “the researcher”, and often refer to their work impersonally, especially in abstracts and summaries:

“The author focuses on the conflicts, stresses, and transformations…”

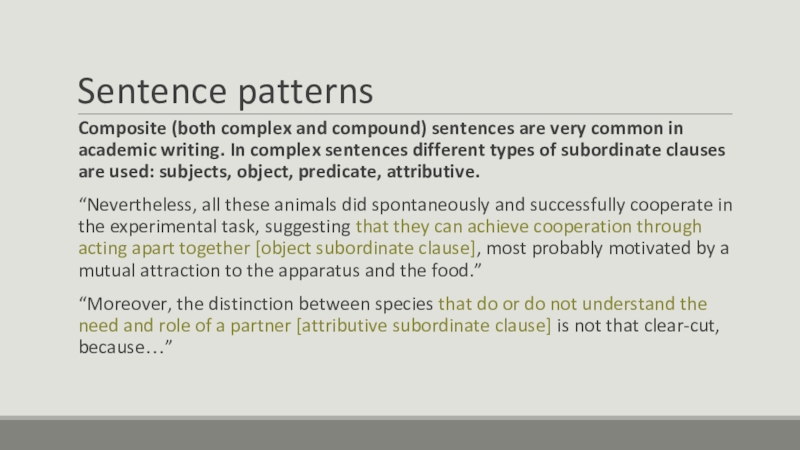

Слайд 35Sentence patterns

Composite (both complex and compound) sentences are very common

in academic writing. In complex sentences different types of subordinate

clauses are used: subjects, object, predicate, attributive.

“Nevertheless, all these animals did spontaneously and successfully cooperate in the experimental task, suggesting that they can achieve cooperation through acting apart together [object subordinate clause], most probably motivated by a mutual attraction to the apparatus and the food.”

“Moreover, the distinction between species that do or do not understand the need and role of a partner [attributive subordinate clause] is not that clear-cut, because…”

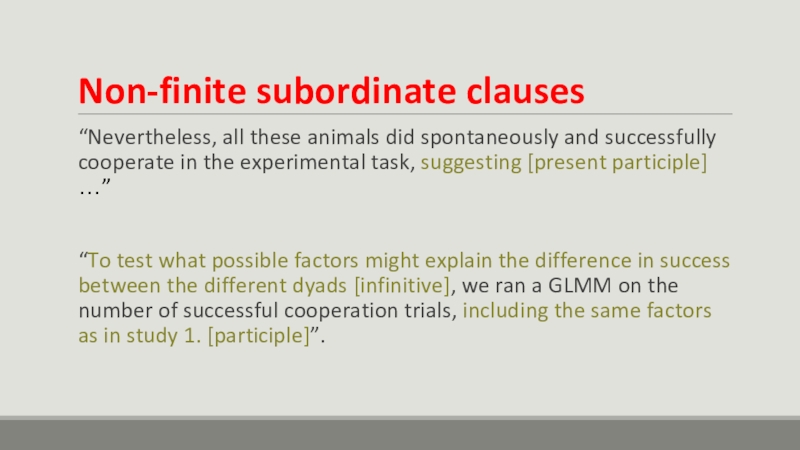

Слайд 36Non-finite subordinate clauses

“Nevertheless, all these animals did spontaneously and successfully

cooperate in the experimental task, suggesting [present participle] …”

“To test

what possible factors might explain the difference in success between the different dyads [infinitive], we ran a GLMM on the number of successful cooperation trials, including the same factors as in study 1. [participle]”.

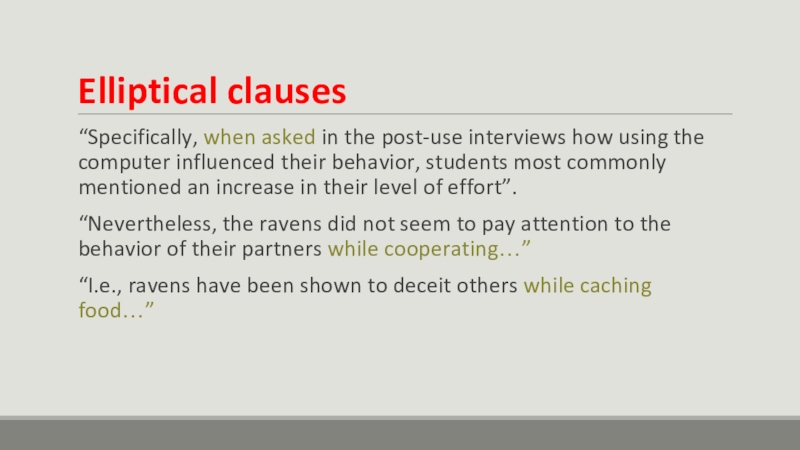

Слайд 37Elliptical clauses

“Specifically, when asked in the post-use interviews how using

the computer influenced their behavior, students most commonly mentioned an

increase in their level of effort”.

“Nevertheless, the ravens did not seem to pay attention to the behavior of their partners while cooperating…”

“I.e., ravens have been shown to deceit others while caching food…”

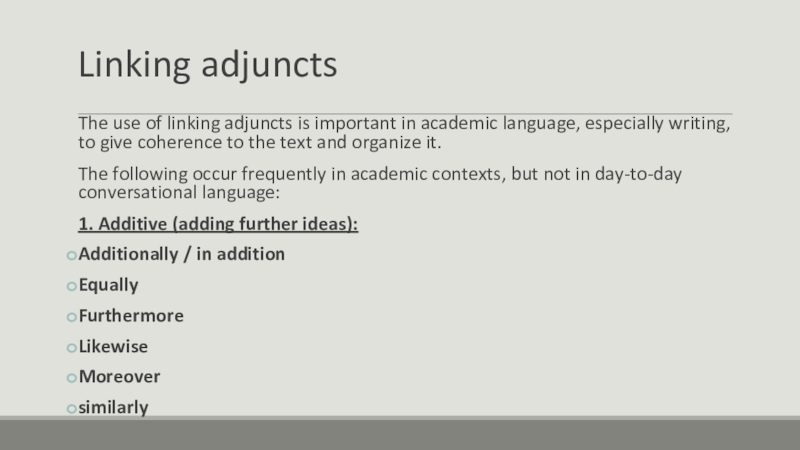

Слайд 38Linking adjuncts

The use of linking adjuncts is important in academic

language, especially writing, to give coherence to the text and

organize it.

The following occur frequently in academic contexts, but not in day-to-day conversational language:

1. Additive (adding further ideas):

Additionally / in addition

Equally

Furthermore

Likewise

Moreover

similarly

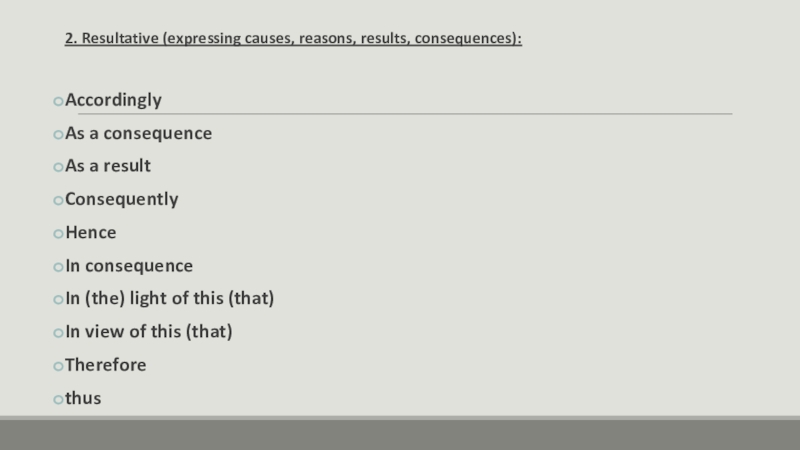

Слайд 392. Resultative (expressing causes, reasons, results, consequences):

Accordingly

As a consequence

As a

result

Consequently

Hence

In consequence

In (the) light of this (that)

In view of this

(that)

Therefore

thus

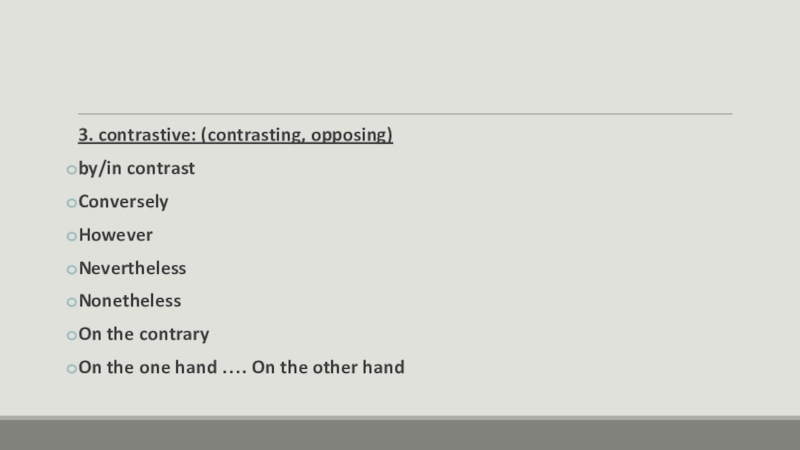

Слайд 403. contrastive: (contrasting, opposing)

by/in contrast

Conversely

However

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

On the contrary

On the one hand

…. On the other hand

Слайд 414. organizational (organizing and structuring the text, listing):

Firstly, secondly, thirdly

Finally

In

brief

In conclusion (to conclude)

In its (their) turn

In short

In sum

(to sum up, summing up, to summarize)

In summary

Lastly

Respectively

subsequently

Слайд 42Linking adjuncts. Examples

However, the ravens did seem to pay attention

to and act upon the outcome of a cooperative interaction

In

particular, we think that the larger the difference in dominance rank, the fewer direct competition is at play

Although the experimenter in our study placed the two rewards within the dyadic setting with ‘the intention’ of an equal reward division, sometimes one of the two birds got two rewards, whereas the other got none.

Alternatively, this pattern may be obtained by associative learning, where a negative experience leads animals not to act anymore.

In contrast, ‘cheaters’ remained motivated to pull (Fig. 3b).

Therefore, more controlled experiments in which defection rates can be manipulated are needed to precisely study the proximate mechanisms

Finally, the results of this study suggest that ravens do not understand the need of a partner while cooperating

Слайд 43References

Ronald Carter, Michael Mccarthy. Cambridge Grammar of English. A

comprehensive guide. / Cambridge University Press, 2013.