the English throne, he firmly believed that the regent derives

power directly from God.James was not interested in reforming the Church of England.

Catholics were forbidden to celebrate Mass (service of worship), and Puritans could not gather for religious meetings.

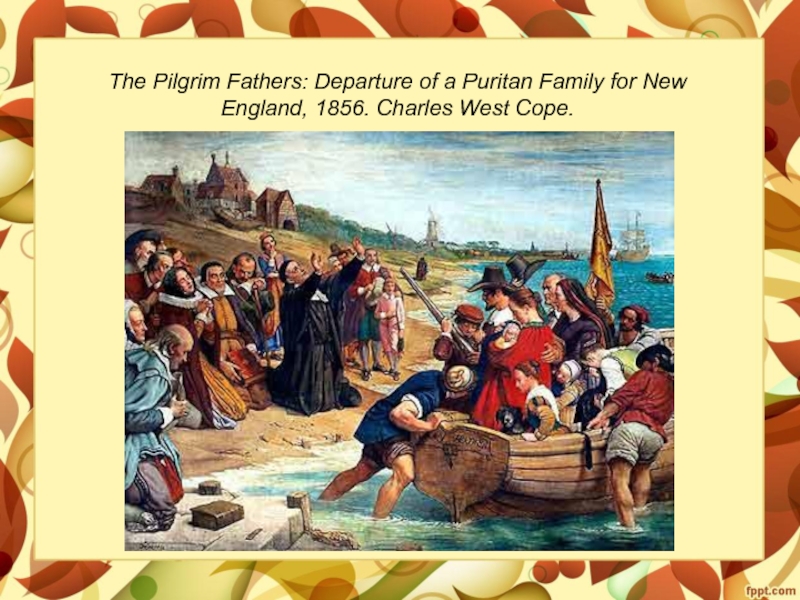

Many religious dissidents left England.

Catholics tended to emigrate to the European continent, particularly France and Italy.

The Puritans first found a home in Holland, and later voyaged to North America, where they established the Plymouth Colony in 1620 in present-day Massachusetts.