Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

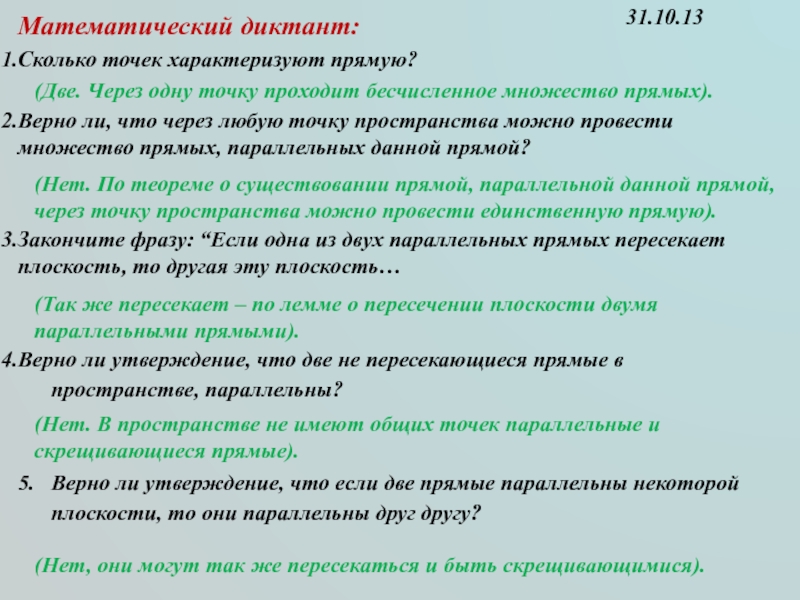

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

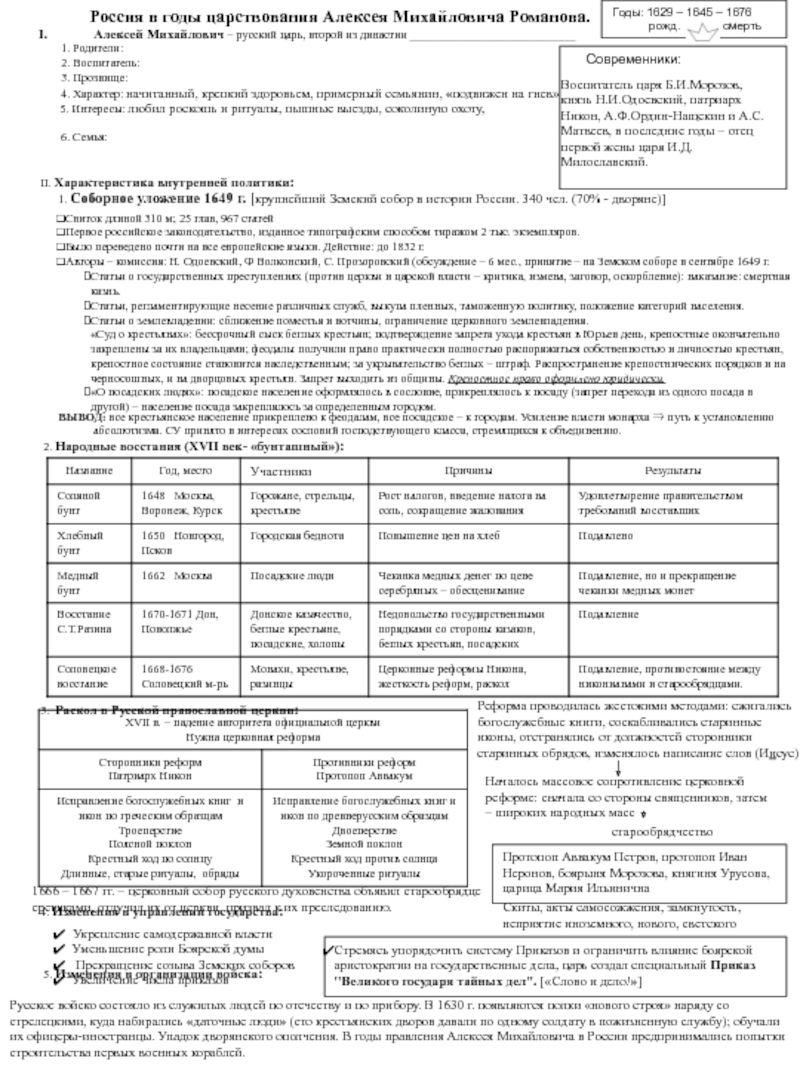

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

History and philosophy of science

Содержание

- 1. History and philosophy of science

- 2. What is a science?Science (from the Latin

- 3. The earliest roots of science can be

- 4. Modern science is typically divided into three

- 5. The structure of science as an activity

- 6. Philosophy was the original inquiry into the

- 7. The modern philosophy of science as a

- 8. According to the domestic researcher T. Leshkevich,

- 9. The formation and development of the philosophy

- 10. Скачать презентанцию

What is a science?Science (from the Latin word scientia, meaning "knowledge")[1] is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 3The earliest roots of science can be traced to Ancient

Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3500 to 3000 BCE.

Their contributions

to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes.Слайд 4Modern science is typically divided into three major branches that

consist of the natural sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics),

which study nature in the broadest sense; the social sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies; and the formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study abstract concepts.Слайд 5The structure of science as an activity can be represented as

a set of three basic elements: the goal – obtaining

new scientific knowledge; the subject – the available empirical and theoretical information to help solve scientific problems; the resources – methods of analysis and communication available to the researcher that help achieve acceptable to the scientific community solution to a problem.Слайд 6Philosophy was the original inquiry into the nature of the

world. (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, etc.) It combined what we'd now

call 'science' with other aspects of reality, and asked all those questions. (So philosophers asked about the origin of the universe, what it was made of, what it was all for, what was ethical, etc., all in one package.) As that knowledge grew and people started specializing, and as philosophers started to realize better the role of controlled observation in gaining certain types of knowledge, and as they learned more about the world to start to impose stable categories on phenomena, the sciences split off from philosophy. So, for example, Aristotle is called the father of biology: he catalogued a great many species, speculated (in a very sexist manner) on biology and reproduction. He also philosophized about what made humans different from other animals. But, it was only some time after him that biology turned into a science with a shared set of standards, research problems, etc. - one could say that before Darwin, biology wasn't distinct from a whole host of other inquiries into life-related subjects. The word "scientists" is a recent invention, formally distinguishing experimental investigators of nature from other modes of inquiry. (Newton called himself a "natural philosopher" because 'scientist' wasn't created yet. And, he probably would have objected even so: he did an awful lot of philosophy (epistemology, especially) in his Principia Mathematica.)Philosophy as the Mother of Science