Слайд 1The Late Ryurikids and Early

Romanovs (1462–1689)

Слайд 3The social disruption and economic damage resulting from Ivan IV’s

adventures persisted in the core of Muscovy well after the

tsar’s death in1584. A political crisis compounded the ill effects of his legacy after his feeble-minded son and successor Feodor died in 1598 without leaving an heir. For the next fifteen years Muscovy endured a rapid succession of rulers, including Boris Godunov who had managed government affairs for his brother-in-law Feodor. Even before Godunov’s death in 1605, champions of competing boyar clans were vying for power with each other as well as with pretenders claiming to be Dmitrii, the youngest son of Ivan IV, who had reportedly died in 1591. The country descended into civil war.

Слайд 4The Swedes, initially invited to assist one faction, seized Novgorod;

their rivals, the Poles, occupied Moscow. Faced with the dismemberment

of Muscovy and reacting to the prospect that the Polish king, a Catholic, might take the Muscovite throne, the leader of the Orthodox Church, whose position had been elevated from metropolitan to patriarch in 1589, took the initiative. While being held in confinement and starving, Patriarch Hermogen smuggled out letters calling for resistance. In response, first one and then a second national militia formed.

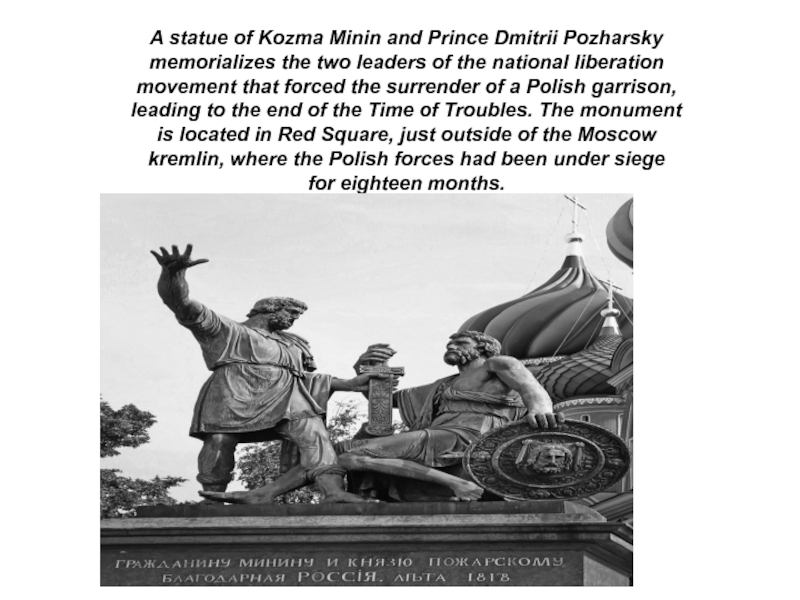

Слайд 5Commanded by Prince Dmitrii Pozharsky and supported with funds raised

by a butcher, Kozma Minin, the militias consisted of townsmen,

provincial servicemen, troops from the pretenders’armies, and Don Cossacks. Although internally divided, this national liberal movement besieged the Polish garrison, which had retreated to the kremlin after burning the surrounding city of Moscow, and forced it to surrender in October 1612. The Time of Troubles, as this period is known, ended in 1613, when an assembly of the land elected a new tsar. Their choice was Michael Romanov, the sixteen-year-old, poorly educated cousin of Feodor, the last Ryurikid ruler.

Слайд 6A statue of Kozma Minin and Prince Dmitrii Pozharsky

memorializes the

two leaders of the national liberation

movement that forced the surrender

of a Polish garrison,

leading to the end of the Time of Troubles. The monument

is located in Red Square, just outside of the Moscow

kremlin, where the Polish forces had been under siege

for eighteen months.

Слайд 7Michael’s ascension to the throne restored the previous order. The

boyar duma, consisting of boyars as well as other high-ranking

courtiers and administrative officials, regained leadership of a reconstituted court. The central chancelleries and appointed governors reestablished control over towns, local officials, and provincial military servicemen. The Orthodox Church reaffirmed its ecclesiastic dominance. Dynastic security remained elusive, however, until Michael produced an heir in 1629 and the Polish king gave up his claim to the Muscovite throne in 1634.

Слайд 8Even then the perpetuation of the Romanov dynasty was not

assured. Although Maria Miloslavskaya, the wife of Michael’s son Alexis,

gave birth to thirteen children, her death in 1669 and that of their eldest son in 1670 left the dynasty’s fate dependent on the frail health of their two remaining sons and influenced Alexis’s decision to remarry. His bride Natalia Naryshkina gave birth to a healthy son, the future Peter the Great, easing fears for the dynasty’s future.

Слайд 9Alexis died suddenly in 1676 and was succeeded by his

ailing fourteenyear- old son, Fedor Alekseevich, or Theodore (1676-82). The

great families struggled for power, the Miloslavskiis related to the late tsar's first wife squabbling with the Naryshkins related to his second wife and with the Matveevs. As the favourites disposed of each other, outsiders managed to grasp the best positions, while Theodore married twice, but without lasting issue, thus leaving behind him a tricky situation at his death in 1682.

Слайд 10The temporary victress in the bloody crisis which followed the

death of Theodore was his elder sister Sofia Alekseevna, or

Sophia, who was installed as Regent (1682-9) in the name of her younger brother Ivan and half-brother Petr or Peter, who were declared joint tsars.

Слайд 11Over the years of Sophia’s reign, in spite of many

plans and projects, nothing significant could be done. Two shocking

uprisings shocked Moscow, one of them was the famous Khovanshchina (1682). In 1689, Sophia tried to raise the archers with the goal of deposing Peter, but this attempt failed: most of the soldier regiments went over to the side of the legitimate king, and from that moment on, his independent rule began.