Разделы презентаций

- Разное

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Futhark

Содержание

- 1. Futhark

- 2. Слайд 2

- 3. Слайд 3

- 4. Old English: Historical BackgroundPre-Germanic Britain -- PictsCeltsRoman BritainGermanic Settlement of Britain

- 5. the PictsPictish is the language of the

- 6. The term Scoti is later used for

- 7. In the sixth century, Christianity was introduced

- 8. The CeltsThe first millennium B.C. was the

- 9. Celtic Houses

- 10. CELTS

- 11. The Gaelic branch survived as Irish in

- 12. The Britonnic branch is represented by Kymric

- 13. Celtic Languages Language

- 14. The Celtic nations where most Celtic speakers are now concentrated

- 15. ToponymyThe major impact of the Celtic language

- 16. Roman BritainJulius Caesar made two raids on

- 17. The expedition of 55 B.C. ended disastrously

- 18. Julius CaesarThe following summer he again invaded

- 19. Emperor ClaudiusIn 43 A.D. Britain was invaded

- 20. UprisingA serious uprising of the Celts occurred

- 21. The district of south was under Roman

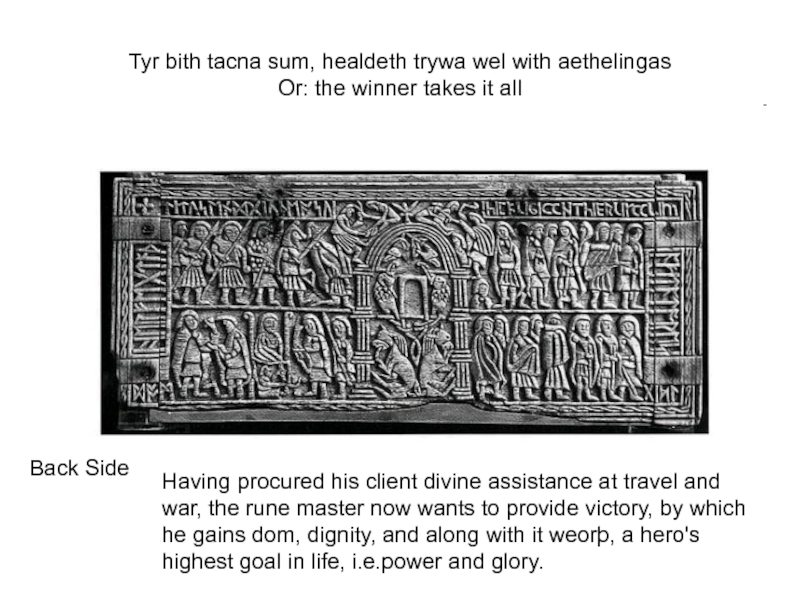

- 22. The houses were equipped with heating apparatus

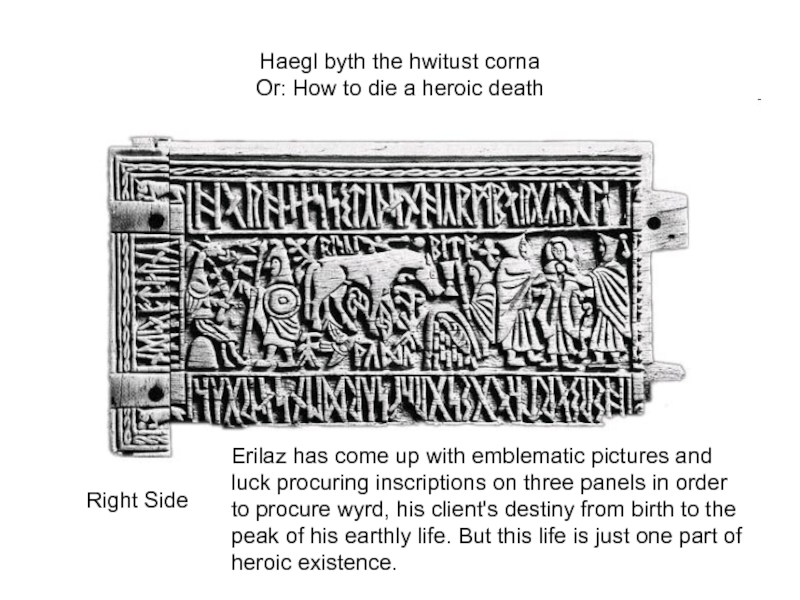

- 23. The upper classes and the townspeople in

- 24. The Use of the Latin language A

- 25. On the whole, there were certainly many

- 26. The end of the Roman occupationThe Roman

- 27. Germanic Settlement of BritainThe 5th century is

- 28. The English historian Bede (673-735) recorded those

- 29. They settled in the east of

- 30. The Angles occupied the Midlands and

- 31. Kent and the Isle of Wight with

- 32. The HeptarchyAt about the middle of the

- 33. It is these 7 kingdoms which provide

- 34. “England” and “English” The Celts called their

- 35. Writers in the vernacular never call their

- 36. From about the year 1000 Englaland (land

- 37. Old English DialectsThe Germanic tribes that settled

- 38. But at the early stages of their

- 39. The main four dialects were:Kentish, spoken in

- 40. West Saxon, spoken in the rest of

- 41. Mercian, spoken in the kingdom of Mercia

- 42. The boundaries between the dialects were not

- 43. In the 9th c. the political and

- 44. Anglo-Saxon Invasion

- 45. Saxon House

- 46. Old English Dialects

- 47. Old English Written AccountsOutline Runic AccountsOld English Manuscripts

- 48. The earliest written records in English are

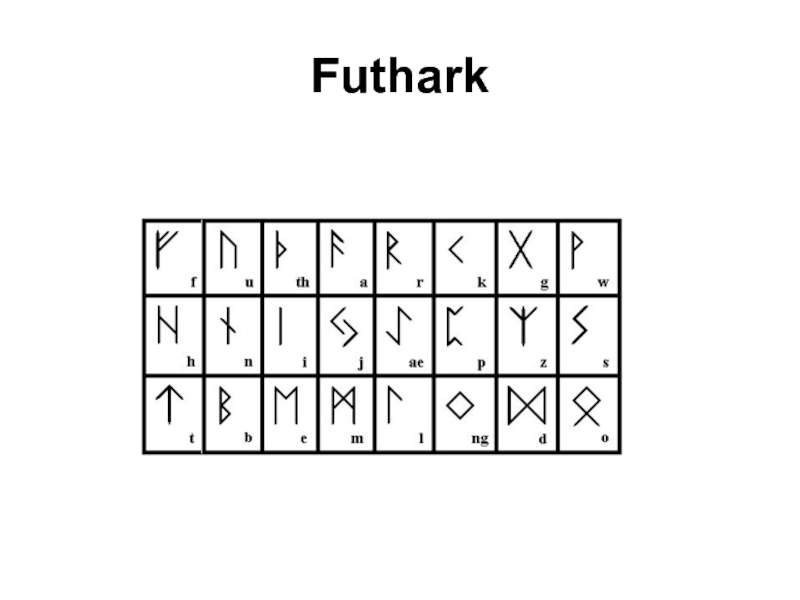

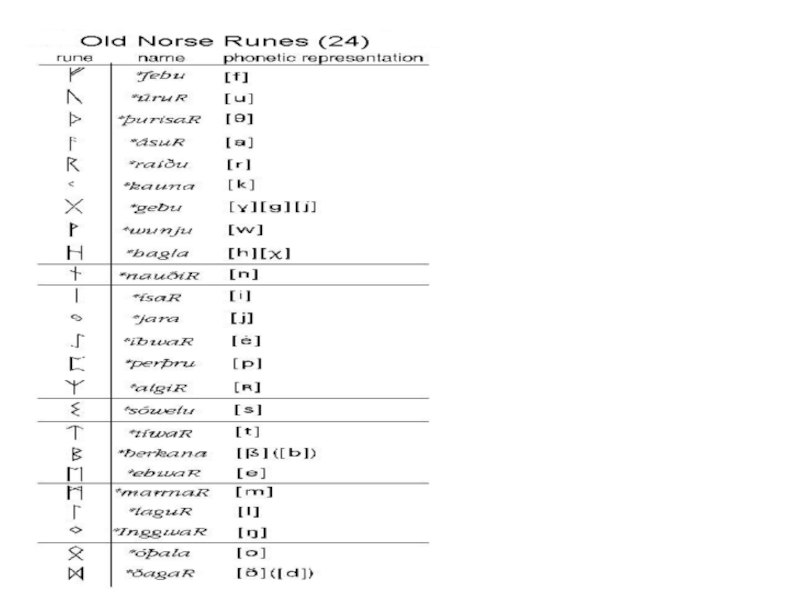

- 49. Futhark In some inscriptions the runes were

- 50. Runic inscriptionsThe two best known runic inscriptions

- 51. The Runic Casket is made of whale

- 52. Feoh byth frofur fira gehwylcum or: money makes the world go roundFront Side

- 53. Rad byth on recyde ... Or:

- 54. Tyr bith tacna sum, healdeth trywa wel

- 55. Haegl byth the hwitust corna Or:

- 56. Of Valhalla and the Final Battle

- 57. Ruthwell Cross in Churchyard, ca. 1880

- 58. The cross originally stood near the present

- 59. Ruthwell Church

- 60. The Ruthwell Cross

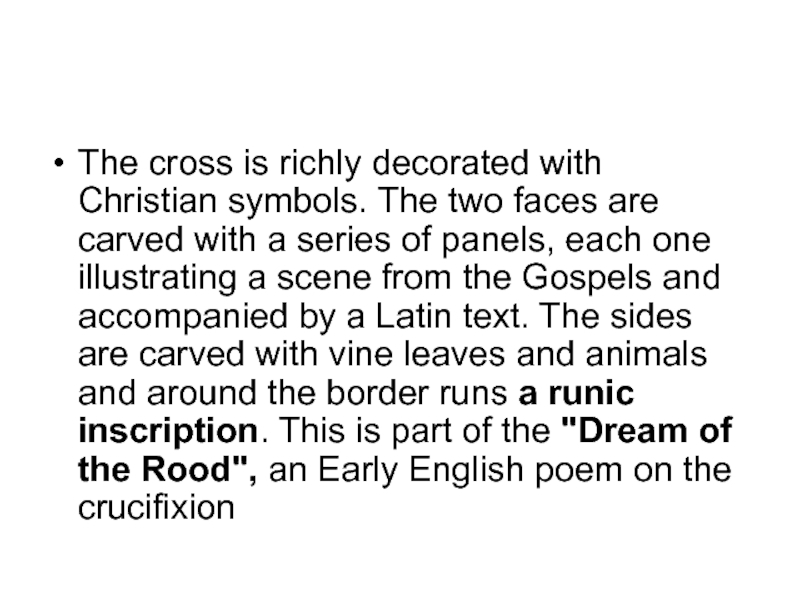

- 61. The cross is richly decorated with Christian

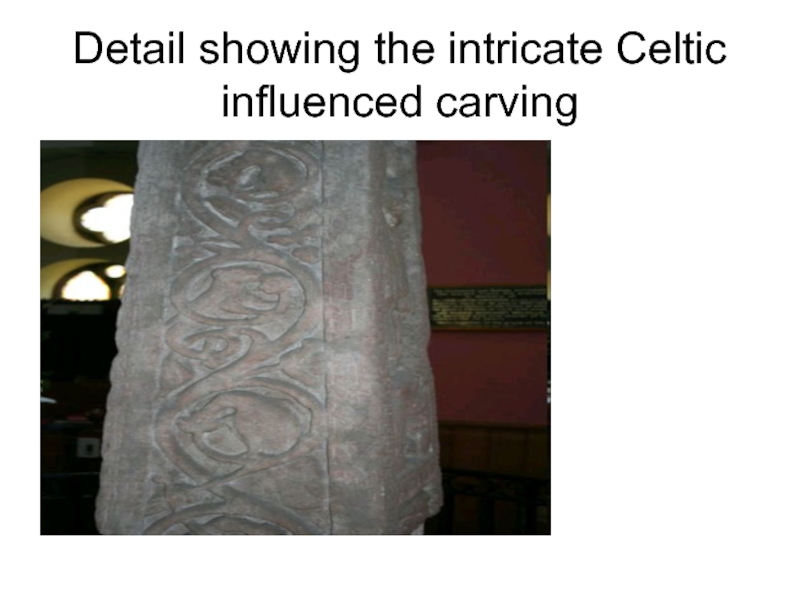

- 62. Detail showing the intricate Celtic influenced carving

- 63. The impressive eighteen feet high cross continues

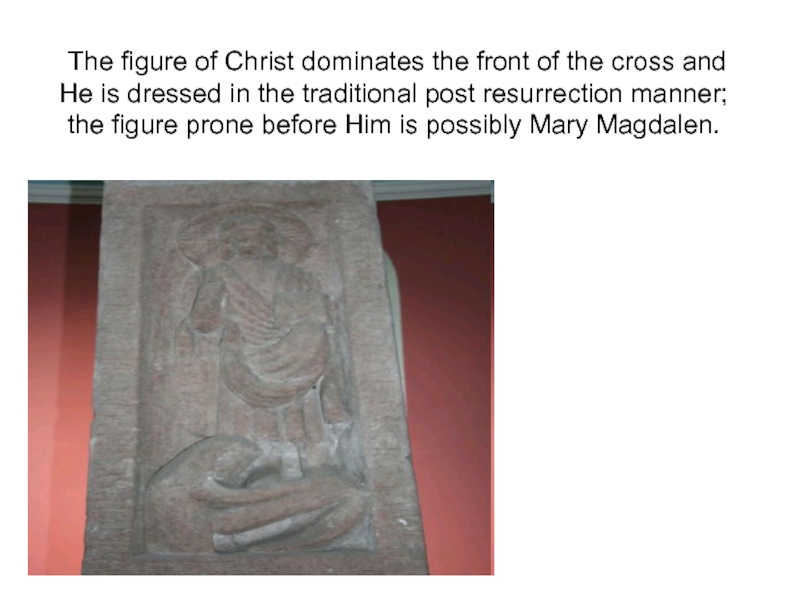

- 64. The figure of Christ dominates the

- 65. Old English Manuscripts Compared with other West

- 66. Writing was mostly in Latin. Sermons could

- 67. Names of English places and people had

- 68. Anglo-Saxon Charters Many documents survived: various

- 69. Anglo-Saxon Charters

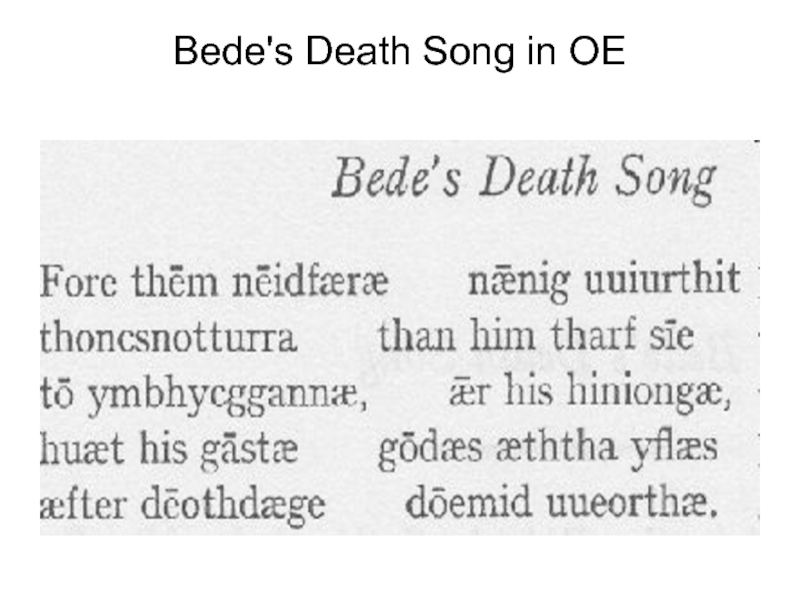

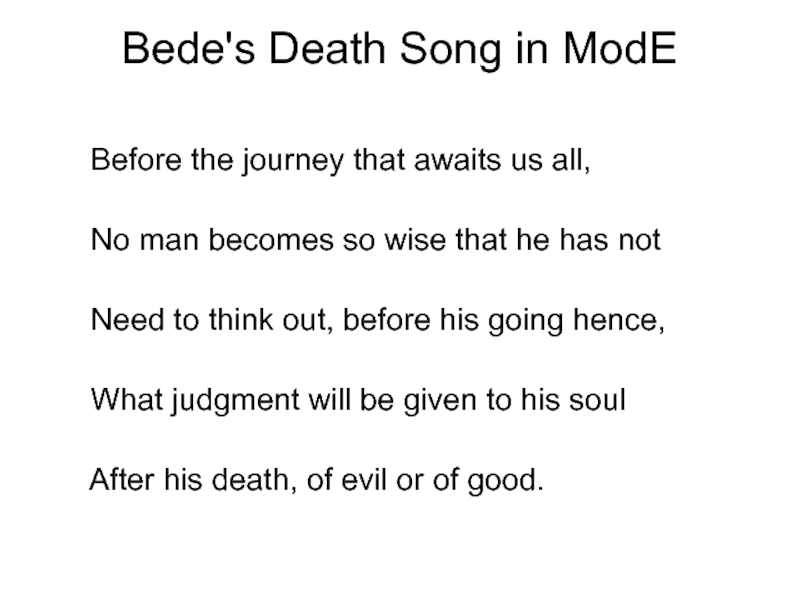

- 70. Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum was written

- 71. Bede's Death Song in OE

- 72. Bede's Death Song in ModE

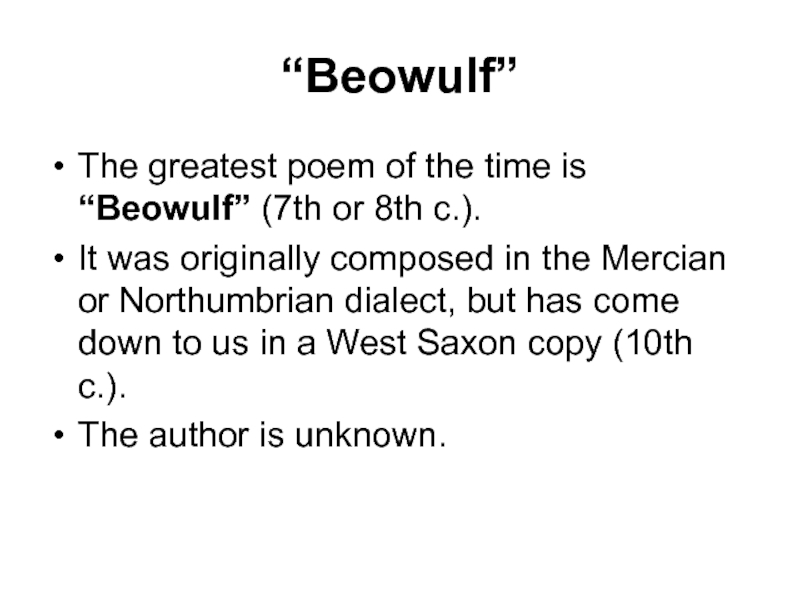

- 73. “Beowulf”The greatest poem of the time is

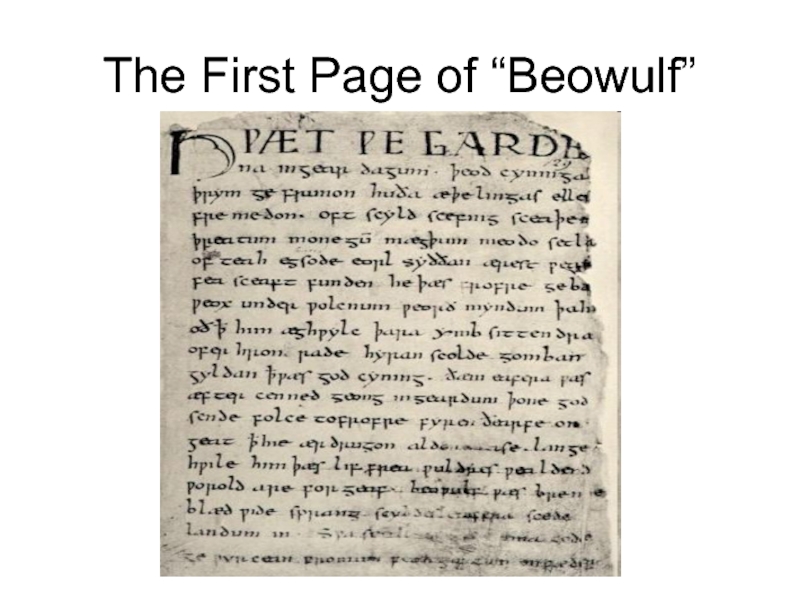

- 74. The First Page of “Beowulf”

- 75. Anglo-Saxon ChroniclesThe earliest samples of continuous prose

- 76. Literary proseLiterary prose appeared in the 9th

- 77. Скачать презентанцию

Old English: Historical BackgroundPre-Germanic Britain -- PictsCeltsRoman BritainGermanic Settlement of Britain

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Слайд 4Old English: Historical Background

Pre-Germanic Britain

-- Picts

Celts

Roman Britain

Germanic Settlement

of Britain

Слайд 5the Picts

Pictish is the language of the people known as

the Picts. The first reference to them is made in

297 AD together with the Hiberni, both mentioned as enemies of the Britanni and the Celts of southern Britain.Слайд 6The term Scoti is later used for Hiberni, this giving

us modern Scotland, Scottish, etc.

If the term is taken

to denote all the people north of the Clyde and Forth then the Picti refer to two distinct groupings, one Celtic and the other non-CelticСлайд 7In the sixth century, Christianity was introduced from the West

of Scotland, the Their language survived.

But in the ninth century

with the arrival of the first Scandinavians the Pictish empire was practically destroyed and the people, driven out of the area, killed or assimilated by Scandinavians.Слайд 8The Celts

The first millennium B.C. was the period of Celtic

migrations and expansion. Traces of their civilization can be found

all over Europe. Celtic languages were spoken over extensive parts of Europe before our era. Later they were absorbed by other IE languages.Слайд 11The Gaelic branch survived as Irish in Ireland. It also

expanded to Scotland as Scotch-Gaelic of the Highlands and is

still spoken by some people on the Isle of Man.Слайд 12The Britonnic branch is represented by Kymric or Welsh in

Modern Wales and by Breton or Armorican spoken in modern

France.Another Britonic dialect in Great Britain is Cornish. It was spoken until the end of the 18th century.

Слайд 13Celtic Languages

Language Area

Status

Welsh (Cymric) Wales

still spoken Cornish Cornwall extinct

Scots Gaelic Scotland still spoken

Manx Isle of Man still spoken

Irish Gaelic Ireland still spoken

Слайд 15Toponymy

The major impact of the Celtic language on English has

been through the names of places and rivers. Places such

as London, Winchester and rivers such as the Thames and Avon are wholly or partly of Celtic origin. Anyway Celtic has left little mark on English: quite apart from the vocabulary, there is little evidence of any influence on morphology, phonology or syntaxСлайд 16Roman Britain

Julius Caesar made two raids on Britain in 55

and 54 B.C.

Caesar attacked Britain for economic reasons: to obtain

tin, pearls and corn. He had some strategic reasons as well. The chief purpose was to discourage the Celts of Britain from coming to the assistance of Celts in Gaul. Слайд 17The expedition of 55 B.C. ended disastrously and his return

the following year was not a great success.

The resistance

of the Celts was unexpectedly spirited. Soon he returned to Gaul. The expedition had resulted in no material gain and some loss of prestige. Слайд 18Julius Caesar

The following summer he again invaded the island after

much more elaborate preparations. This time he succeeded in establishing

himself in the southeast. Julius Caesar exacted tribute from the Celts (which was never paid) and again returned to Gaul. Britain was not again troubled by Roman legions for nearly a hundred yearsСлайд 19Emperor Claudius

In 43 A.D. Britain was invaded by Roman legions

under In 43 A.D. Britain was invaded by Roman legions

under Emperor Claudius. An army of 40 thousand was sent to Britain and within 3 years had subjugated the people of central and southeastern regions.Слайд 20Uprising

A serious uprising of the Celts occurred in 61 A.D.

under Boudicca (Boadicea), the widow of one of the Celtic

chiefs. 70 thousand Romans and Romanized Britons were massacred. The Romans never penetrated far into the mountains of Wales and Scotland. They protected the northern boundary by a stone wall stretching across England.Слайд 21The district of south was under Roman rule for more

than 300 years. Britain was made a province of Roman

Empire. Many towns with mixed population grew and London was one of the most important trading centres of Roman Britain. Where the Romans lived and ruled, there Roman ways were found: great highways soon spread from London to the north, the northwest, the west and the southwest.Слайд 22The houses were equipped with heating apparatus and water supply,

their floors were paved in mosaic. Roman dress, Roman ornaments

and utensils were in general use.By the 3rd century Christianity had made some progress in the island.

Слайд 23The upper classes and the townspeople in the southern districts

were Romanized, but rural areas were less Romanized.

Population in

the north was little affected by the Roman occupation and remained Celtic both in language and custom Слайд 24The Use of the Latin language

A great number of

inscriptions have been found, all of them in Latin. The

majority of these were military or official class documents.Latin did not replace the Celtic language in Britain.

Слайд 25On the whole, there were certainly many people in Roman

Britain who habitually spoke Latin or upon occasion could use

it.But its use was not sufficiently widespread to cause it to survive, as the Celtic language survived.

Слайд 26The end of the Roman occupation

The Roman occupation lasted nearly

400 years.

It ended in the early 5th century.

In

410 A.D. the Roman troops were officially withdrawn to Rome. The Empire was collapsing due to internal and external causes.Слайд 27Germanic Settlement of Britain

The 5th century is the age of

increased Germanic expansion.

About the middle of the century several

West Germanic tribes invaded Britain and colonized the island by the end of the century. Слайд 28The English historian Bede (673-735) recorded those events in “Historia

Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum” (Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation). He

wrote that England was colonized by three Germanic tribes: Angles, Saxons and Jutes. Bede reported that the Saxons were invited by the Romanised British to help them fight against their enemies from the north.Слайд 29 They settled in the east of England and the

newcomers invited others of their tribes to settle there. It

happened in 450 A.D. While there may be some elements of truth in this, Saxons have been plundering the east coast of England for many years. When the Roman armies were withdrawn in 410, Britain became more exposed to the attacks.Слайд 30 The Angles occupied the Midlands and north of the

country.

The Saxons settled all of Southern England except Kent

and parts of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Their name survives in various county and regional names, such as Sussex “South Saxons”, Wessex “West Saxons” and so on. Слайд 31Kent and the Isle of Wight with parts of neighbouring

Hampshire were settled by the Jutes, though the dialect of

Kent is referred to as Kentish rather than Jutish.Слайд 32The Heptarchy

At about the middle of the 6th c. it

was possible to recognize several distinct regions which lead their

own forms of government. This became recognized as the Heptarchy, or 7 kingdoms – Wessex, Sussex, Kent, Essex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria.Слайд 33It is these 7 kingdoms which provide the basic for

most dialect study of this period, though written remains are

not found until the beginning of the 8th c.Politically, no one of these kingdoms was able to achieve supremacy over the others.

Слайд 34“England” and “English”

The Celts called their Germanic conquerors Saxons

indiscriminately. The land was called Saxonia.

But soon the terms

Angli and Anglia occur besides Saxons and refer not to the Angles individually but to the West German tribes generally. Слайд 35Writers in the vernacular never call their language anything but

Englisc (English).

The word is derived from the name of

Angles (OE Engle). The land is called Angelcynn.Слайд 36From about the year 1000 Englaland (land of the Angles)

begins to take its place.

It is impossible to say

how much the speech of the Angles differed from that of the Saxons or that of the Jutes. The differences were certainly slight. Слайд 37Old English Dialects

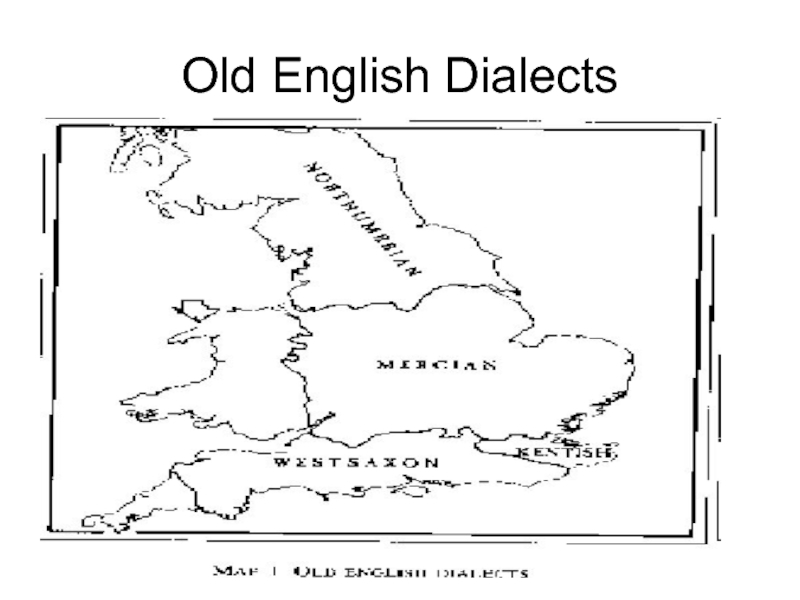

The Germanic tribes that settled in Britain in

the 5th and 6th c. spoke closely related dialects belonging

to the West Germanic group.Eventually they began to use English.

Слайд 38But at the early stages of their development the dialects

remained disunited.

OE dialects acquired certain common features that distinguished

them from the continental Germanic languages. Слайд 39The main four dialects were:

Kentish, spoken in the area now

known as Kent and Surrey and in the Isle of

Wight. This dialect developed from the tongue of the Jutes and Frisians.Слайд 40West Saxon, spoken in the rest of England south the

Thames and the Bristol Channel, except Wales and Cornwall. There

Celtic dialects were preserved.Слайд 41Mercian, spoken in the kingdom of Mercia (the central region,

from the Thames to the Humber).

Northumbrian, spoken from the Humber

north to the river Forth.Слайд 42The boundaries between the dialects were not distinct and may

be movable. None of the dialect was dominant, they enjoyed

equality.By the 8th c. the centre of English culture had shifted to Northumbria and the Northumbrian dialect got more prominence.

Слайд 43In the 9th c. the political and cultural centre moved

to Wessex and the West Saxon dialect is preserved in

a greater number of accounts than all the other dialects.Towards the 11th c. the West Saxon dialect developed into a bookish language.

Слайд 48The earliest written records in English are inscriptions on hard

material made in runes.

The word “rune” originally meant “secret”,

“mystery”. Each character indicated a separate sound. Слайд 49Futhark

In some inscriptions the runes were arranged in a

fixed order making a sort of alphabet. It was called

futhark. The letters are angular, straight lines are preferred. This is due to the fact that runic inscriptions were cut on hard material: stone, bone or wood. The number of runes was from 28 to 33 (new sounds appeared).Слайд 50Runic inscriptions

The two best known runic inscriptions in England are:

1).

on a box called the “Franks Casket”

2) a short text

on a stone cross in Dumfriesshire near the village of Ruthwell known as the “Ruthwell Cross”. Both records are in the Northumbrian dialect.Слайд 51

The Runic Casket is made of whale bone. As for

the size of the plates, parts of the jaw have

been used. The measurements of the panels:Front and Back ~ 23 cm x 10.5 cm

the Sides ~ 19 cm x 10.5 cm

the Lid (remaining portion) ~ 22,5 cm x 8.5 cm

Franks Casket

Слайд 53Rad byth on recyde ... Or: On the road again

...

Left Side (a ride) seems easy to every warrior while

he is at home, and very courageous to him who traverses

the highroads on the back of a stout horse.

(Ags. Runic Poem)

Слайд 54Tyr bith tacna sum, healdeth trywa wel with aethelingas Or:

the winner takes it all

Back Side

Having procured his client divine

assistance at travel and war, the rune master now wants to provide victory, by which he gains dom, dignity, and along with it weorþ, a hero's highest goal in life, i.e.power and glory.Слайд 55Haegl byth the hwitust corna Or: How to die a

heroic death

Right Side

Erilaz has come up with emblematic pictures and

luck procuring inscriptions on three panels in order to procure wyrd, his client's destiny from birth to the peak of his earthly life. But this life is just one part of heroic existence.Слайд 56Of Valhalla and the Final Battle Or: Even gods can

fight in vain ...

The Lid

The rune master has provided a

perfect life from birth to death. But his assistance reaches beyond that border. The valkyrie has taken her human companion to Walhalla so that he has his seat among Woden's warriors. There he is preparing himself for the final battle (O.N. Ragnarök), a fight against the Frost Giant on the side of the gods, the aesir. And that is what this panel is about.Слайд 58The cross originally stood near the present church. In 1664

it was pulled down and smashed on the instructions of

the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. In 1802 it was re-erected in the garden and in 1887 was moved to a specially built place in the church.Слайд 61The cross is richly decorated with Christian symbols. The two

faces are carved with a series of panels, each one

illustrating a scene from the Gospels and accompanied by a Latin text. The sides are carved with vine leaves and animals and around the border runs a runic inscription. This is part of the "Dream of the Rood", an Early English poem on the crucifixionСлайд 63The impressive eighteen feet high cross continues for two metres

behind the altar and below the floor level.

Слайд 64 The figure of Christ dominates the front of the

cross and He is dressed in the traditional post resurrection

manner; the figure prone before Him is possibly Mary Magdalen.Слайд 65Old English Manuscripts

Compared with other West Germanic peoples, the

Anglo-Saxons are exceptional in their early use of writing and

in the large amount of writing that survives.Writing in those times was very much the property of the church and written texts were largely produced in monastic scriptoria.

Слайд 66Writing was mostly in Latin. Sermons could be delivered orally

in English even if they were written down and survived

in their written form in Latin.But some writing in English was needed.

Слайд 67Names of English places and people had to be written

down.

Certain traditional features of Anglo-Saxon life, such as the

law, would need to reflect the language in which it had been handled down in traditional form to maintain ancient legal practices.Слайд 68Anglo-Saxon Charters

Many documents survived: various wills, grants, deals of

purchase, agreements, proceedings of church councils, laws.

They are known

as “Anglo-Saxon Charters”. Слайд 70Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum was written in Latin in

the 8th c. but it contains an English fragment of

5 lines known as “Bede’s Death Song” and a religious poem of nine lines “Caedmon’s Hymn”.Слайд 72Bede's Death Song in ModE

Before the

journey that awaits us all,

No man

becomes so wise that he has not Need to think out, before his going hence,

What judgment will be given to his soul

After his death, of evil or of good.

Слайд 73“Beowulf”

The greatest poem of the time is “Beowulf” (7th or

8th c.).

It was originally composed in the Mercian or

Northumbrian dialect, but has come down to us in a West Saxon copy (10th c.). The author is unknown.

Слайд 75Anglo-Saxon Chronicles

The earliest samples of continuous prose are Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.

These are brief account of the year’s happenings made at

various monasteries. Слайд 76Literary prose

Literary prose appeared in the 9th c. which witnessed

a flourishing of learning and literature during King Alfred’s reign.

King Alfred translated from Latin books on geography, history, philosophy.One of his most important contributions is Orosius’s World History.